San Francisco’s Planning Department says this year’s Housing Element is the first to center on race and equity, but housing advocates say the eight-year plan doesn’t include a comprehensive strategy to build enough affordable housing.

For the first time, San Francisco’s comprehensive housing strategy plan recognizes housing as a human right and explicitly names race and equity as focal points. But community advocates say the document prioritizes market-rate development over the needs of the communities the city says it wants to serve.

Called the Housing Element, the eight-year plan that California cities and counties must submit to the state for approval is a blueprint for local governments to show how they will keep up with population growth. San Francisco has been charged with building 82,000 units between 2023 and 2031, of which almost 57% must be affordable.

The plan notes that, “San Francisco’s housing problem is a racial and social equity challenge and an economic problem,” and later acknowledges that “many communities of color, especially the city’s Black and American Indian communities, have experienced deep, multi-generational, dispossession, harm, and near erasure, experiences that have yet to be fully told, documented, recognized, and repaired by City actions.”

To address some of these harms and commitments it made in 2020, the Planning Department branded this Housing Element as the city’s first housing plan centered on racial and social equity.

However, many community activists said that, while recognizing and rectifying the harms of discriminatory housing policies is a worthy goal, the plan doesn’t create a roadmap to deliver on those aims.

“I don’t feel like we’ve created a plan yet that we’ve set up to succeed,” said Charlie Sciammas, policy director at the Council of Community Housing Organizations, a grassroots coalition of advocates and developers focused on affordable housing and low-income communities. “It’s great to have all the lofty goals, but if the city hasn’t committed to put in place all the pieces we need to make sure we can bring it to fruition — that means a strong start to our public investments, and transforming our public institutions to truly prioritize affordable housing — it’s hard to count this as a win.”

The department began by researching and drafting key policy ideas to share with the public, before asking communities to reflect on the draft ideas and share their own housing challenges. It then updated the first draft based upon these interactions, returning to communities once again to refine policies. In these periods, the Planning Department also carried out focus group discussions with vulnerable populations and collaborated with community-based organizations on informational meetings and listening sessions, including events in Cantonese and Spanish, holding hearings open to the public and conducting a survey of residents.

In recent weeks, the department has been moving to finalize the draft, participating in a meeting at the Board of Supervisors and holding several commission hearings open to the public.

Housing development in San Francisco has not kept up with goals set by the state for the most recent housing cycle, with only 34% of the target for affordable housing units being produced. In contrast, developers built more market-rate units and achieved 150% of the city’s goal for that type of housing.

Data from the Planning Department shows that more market-rate housing is being produced in San Francisco than required under the 2014 Housing Element, but not enough affordable housing is being created to hit the 2014 targets.

Community-driven solutions

Dozens of San Francisco residents, many of them identifying as people of color or low-income, showed up in person and virtually to a Nov. 15 Board of Supervisors hearing to air their concerns about the city’s plan. Groups like the Race and Equity in All Planning Coalition, a coalition of 39 community-based organizations that came together during the pandemic, have also raised concerns.

“There’s a lot of interesting language in this housing element around centering on racial and social equity, and the three dozen or so organizations that are in the Race and Equity in All Planning Coalition from all over the city feel like it really doesn’t do that,” said Joseph Smooke, one of the group’s organizers.

Smooke later credited the Planning Department for making some revisions based on the coalition’s feedback, but said, “what we’re looking at is a Housing Element that removes communities’ voices, and does not prioritize affordable housing.”

In a document critiquing the city’s plan and proposing their own strategies to build affordable housing, the coalition described the city’s proposed Housing Element as “largely a market-based housing production plan that assumes three insufficient strategies for affordable housing.” The coalition’s document, known as the Citywide People’s Plan for Equity in Land Use, draws on development ideas generated by local communities and neighborhoods as the basis for its equitable-strategy action plan regarding affordable housing production and displacement prevention.

Authors of the People’s Plan maintain that the proposed Housing Element relies on market-rate development to achieve race and equity goals. They criticized this framework, saying that developers prioritize profit over racial equity and that building more market rate housing will not lower prices due to the commodification of the housing market.

“Instead of trying to fix displacement with displacement, we’re trying to demand creative strategies for affordable housing, such as funding for small affordable housing projects, buying existing buildings, the small sights acquisition program,” said Amalia Macias-Laventure, a member of West Side Tenants Association, at a rally before the Board of Supervisors hearing on Nov. 15.

“In my lifetime alone, I’ve seen family after family, community member after community member, move out of San Francisco because they simply cannot afford to live here,” said Arianna Antone-Ramirez, a citizen of the Tohono O’odham Nation and a board member and adviser at the American Indian Cultural Center. “It’s insulting to our community when the Planning Department wants to come to us and ask us to think creatively about fitting in market rate housing with the affordable housing to be built.”

Another partial solution raised by the coalition and the Council of Community Housing Organizations was encouraging the city to increase land banking for affordable developments — i.e., purchasing land for later use without a specific development plan in mind.

Sciammas said that affordable developments have a hard time competing with market-rate developers and other private investors to acquire sites.

Sciammas commended the Planning Department for naming land banking as a “major strategy” in the most recent draft of the plan, but wrote in an email that “Our biggest concern is that the policy action will not go very far without a major commitment of public investments and a realignment of the city’s approach to affordable housing.”

Members of the coalition also pushed for community input in identifying possible sites and an increased role for the Mayor’s Office of Housing and Community Development and housing-focused nonprofits in preparing for more affordable site purchases and eventual housing production.

No silver bullet

Speaking to the criticisms outlined in the Peoples’ Plan, the Planning Department cited economic barriers.

“Some of the community leaders within that organization want to elevate the affordable housing or housing that is produced by government and nonprofit organizations, and we are with them,” said Miriam Chion, the department’s community equity director. “At the same time, we have an economic paradigm within which we function, which requires private investment, and our job is to guide those private investments. We would be failing if we didn’t provide that.”

Chion emphasized the department’s efforts in reaching out to and listening to affected communities as it went about creating the Housing Element, which community advocates also recognized.

“We’ve made a concerted effort over the last two years to reach out to communities that haven’t typically been a part of these discussions, especially communities of color, lower income communities, to get their voices in,” Chion said. “It was going to them, to where they were, and having the conversations with them on their own terms.”

While the plan describes various communities’ desires to hear the city acknowledge and repair past harms, Planning Director Rich Hillis did not point to specific strategies when asked to explain how the city would do that.

“There’s not one silver bullet,” Hillis said. “There’s a host of actions, which is why this document is as long and dense as it is.”

New state requirements

San Francisco’s intention to address equity in housing align with California’s new requirements to “affirmatively further fair housing” in housing elements. This means adopting measures to combat discrimination, desegregate neighborhoods and transform racially concentrated areas of poverty into “areas of opportunity.”

Since 2005, only 10% of new affordable housing in San Francisco has been built in “higher opportunity areas” — defined by higher incomes, home ownership rates, and educational, employment and health outcomes. These areas also have higher concentrations of white households. The Planning Department points to zoning as one driving factor, noting that 65% of the land in these areas is limited to one or two-unit residential zoning.

In the new plan, the Planning Department recognizes the historical reasons for those differences, and proposes some policies in response. One of the biggest divergences the department sees between the current element, which covers 2015 through January 2023, and the proposed element is the fact that the new plan considers the differing needs and histories of neighborhoods across the city.

“We treat communities a little bit differently in this,” Hillis said. “We’re trying to build housing in those well-resourced neighborhoods that haven’t seen a lot of housing, and focusing efforts and actions around housing stability.”

San Francisco’s new Housing Element proposes rezoning to hit state mandates and developing more housing in well-resourced neighborhoods.

“We’ve got to engage with and build trust with communities,” Chion said. “Communities used to fight against the Planning Department and the Planning Commission — we welcome the challenges but it is also important to build collaboration. This Housing Element points us in that direction.”

However, some community advocates said the plan broadly focuses on development in these areas when it should be focuses on affordable development specifically.

“What we’re seeing is the planning is basically directing a density strategy instead of actually directing an affordability strategy,” Smooke later said in an interview.

Examining history and its ongoing impacts

The challenges communities of color face with housing instability are deeply rooted in the region’s history. The Bay Area was the birthplace of many exclusionary housing policies that are now common across the country.

In San Francisco, zoning was used to criminalize the Chinese community. The Cubic Air Ordinance and anti-laundry laws targeted Chinese communities in the 1870s, though both were found to be illegal in court. The former required 500 feet of cubic space for each person in a lodging house and was used to jail thousands of Chinese residents, while the latter gave the Board of Supervisors the ability to restrict where laundries could be located, the majority of which were operated by Chinese people. An outright attempt at segregation, the Bingham Ordinance, passed in 1890 and banned Chinese residents from certain areas of the city — giving them 60 days to move or be charged with a misdemeanor and face jail time.

Racial covenants were common between the late-nineteenth and mid-twentieth century, wherein white property owners and developers would write in clauses that barred people of color, especially African Americans, from buying or renting property.

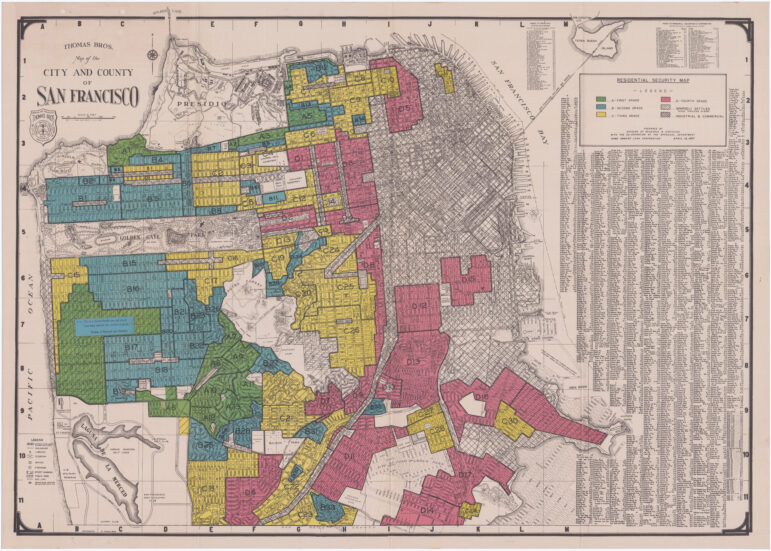

Another policy, redlining, which began in the 1930s and was named for the colorful maps used to demarcate areas deemed “hazardous” for lending, denied borrowers access to credit based upon the racial or socioeconomic makeup of their neighborhoods. These maps contributed to divestment in Black communities and segregation across the country.

In the 1950s, San Francisco began planning the demolition of areas deemed “slums” or “blighted,” many of which were Black cultural hubs, in the name of urban renewal. The Western Addition was one such neighborhood. It encompassed most of Japantown and the Fillmore District — known then as the “Harlem of the West” — which itself was populated by Black communities in the wake of the forced internment of Japanese Americans during World War II. All in all, more than 20,000 families were estimated to have been displaced through the razing of these thriving neighborhoods.

Today, communities are still dealing with the fallout of these discriminatory policies regarding housing access and wealth building. The Urban Displacement Project found that 87% of San Francisco’s formerly redlined neighborhoods are currently undergoing displacement. San Francisco’s Black population declined by 41% between 1990 and 2020. American Indian and Alaskan Natives are also experiencing displacement, with their presence in the city dropping 16.7% between 2014 and 2019.

On Dec. 15, the Planning Department will hold a hearing to adopt the final draft Housing Element, which must be adopted by the city by Jan. 31 and found compliant by the state if it hopes to avoid fines, losing out on affordable housing funding sources and other penalties. Chion of the Planning Department said on Tuesday that the plan is close to being adopted in accordance with state guidelines, saying that only three minor changes still remain.