The article was originally reported and published by MindSite News, a national nonprofit news outlet that reports on mental health.

Sign up for the MindSite News daily newsletter here.

The first time Keith B. walked through the door of Rypins House, a residential treatment home for older adults run by the Progress Foundation in San Francisco, he thought to himself: “Where is everyone?”

A former luxury car salesman and behavioral health worker, the 60-year-old had spent years cycling in and out of institutions — detox centers, hospitals, homeless shelters. They were usually crowded and noisy, with lots of yelling. He was always on alert, afraid people would steal from him. Keith lives with bipolar disorder and took to self-medicating with street drugs back in the 90s. But as he aged, he wanted a calm space to sort his life out. Start making plans to get a hip replacement. Acquire his real estate license. Go back home to Philadelphia.

Celeste Hamilton Dennis / MindSite News

“We don’t see addiction as being something separate from mental health,” says Jim Roberts, Progress Foundation’s director of residential treatment, pictured standing outside Rypins House.Keith came to Rypins House in August last year after a drug relapse that left him on the streets of San Francisco for four days, unable to sleep. He first sought help from the Dore Urgent Care Clinic, another Progress Foundation facility that offers a place for people to stay and get help for a few days when they’re in a crisis. It’s a gentler, cheaper alternative to an emergency room visit. From there, he was given a bed for up to six months at Rypins, a butter-yellow Victorian house in a neighborhood far from the Tenderloin, where he doesn’t owe drug dealers money and has a better shot at staying clean.

More than 1 million California adults like Keith — and 19.4 million Americans — live with both a serious mental illness and substance use disorder. In fact, roughly half of all people with severe mental illness are thought to also have a co-occurring substance use disorder. Traditionally, treatment programs target one of these populations or the other. Progress Foundation is one of the few across the country serving people who have both — so-called dual diagnosis patients. What’s especially unusual is that two Progress homes are reserved for people 55 and older.

One of his first nights in the house, Keith was sitting in the living room all by himself watching ‘Coming to America.’ He put the movie on pause to go to the bathroom and when he came back, nobody had sat in his chair or taken the remote control.

“It just hit me like, ‘Wow, I’m really in a peaceful, quiet environment,’” he said. “I’d almost gotten used to the chaos of the street and institutions. They’re not good places to heal. This place doesn’t feel like a program. It feels more like a home.”

Rypins House: A respite from the storm

Progress Foundation was founded in 1969 on the belief that recovery is possible at any age. It began as an alternative to medical models that largely rely on hospitalization and clinical treatment. Instead, it employs a social rehabilitation approach, and has created a variety of programs to meet people’s needs at different stages. Nurse practitioners rotate between the programs, and clients can take medication they administer themselves. All of the programs provide clients with a home-like environment where they can learn independent-living skills.

Celeste Hamilton Dennis / MindSite News

Executive Director Steve Fields has led the Progress Foundation since co-founding the agency in 1969.“Our clients are constantly being told, ‘You’re gonna be ill the rest of your life,’” says Progress Foundation Executive Director Steve Fields, who has led the organization since co-founding it. “We’re trying to show them a pathway out of thinking so narrowly about themselves. We’re saying, who knows where you can end up? You may have episodic crises, but that’s not your definition. We can work with you on a recovery plan because we believe that you can reach a level of functioning in the community.”

Rypins House and the Foundation’s ten other residential programs — each tailored to a different need — all attempt to address a huge problem in the mental health system: the lack of places people can go after they’ve been treated for a crisis. Fewer than 50% of patients discharged from a hospital following emergency mental health treatment are seen by a therapist or other provider within seven days, according to data gathered from health plans, and that number drops below 30% when it comes to Medicare patients.

There simply isn’t enough capacity to meet the need, says Tom Insel, a psychiatrist and former director of the National Institute of Mental Health. This is due to a shortage of beds, workers and safety net services as well as residential treatment programs. “The problem isn’t just people entering the hospital. It’s how they leave. There’s no practical plan for most people when they are discharged,” he says.

Progress Foundation is funded primarily through county health departments, and in San Francisco, that means it prioritizes clients who come from the inpatient unit at Zuckerberg San Francisco General Hospital as well as nursing homes that serve patients on Medicare or Medicaid. The agency also receives referrals from the jail system, as well as people like Keith who come from other Progress programs. This is the Foundation’s attempt to create a true continuum of care — a system that can help address the needs of patients at different stages and with different needs.

Celeste Hamilton Dennis / MindSite News

Residential Treatment Director Jim Roberts.“We don’t see addiction as being something separate from mental health,” says Jim Roberts, director of residential treatment, supported living and permanent housing. “If anything, we see some of these substance abuse issues as a symptom and behavior of their mental health.”

The Progress Foundation’s wide network

Dore Urgent Care Clinic — where people can stay up to 23 hours to avoid unnecessary hospitalization — is on one end of the spectrum. On the other end are the foundation’s transitional programs where people can stay for between three months and one year.

There’s not much research on the benefits of longer stays for people who have dual diagnoses, but a 2001 study showed that while people in short-term dual-diagnosis programs tend not to remain long in the programs or fare very well, those in long-term programs did better: They were more apt to reduce their substance use and less likely to become homeless afterward.

The foundation also has a handful of cooperative living apartments and three independent living apartment buildings. Clients need to be enrolled in or applying for Medi-Cal, and to be San Francisco residents in order to receive the more intensive services. Undocumented immigrants are now eligible too, since, as of January 1, a new state law provides Medi-Cal to all low-income residents, regardless of immigration status.

Celeste Hamilton Dennis / MindSite News

The Progress Foundation houses seek to create a homey, comfortable atmosphere.The program is a bargain, Fields says. He estimates that a bed at a Progress residential treatment program costs around $300 per day compared with $1000 to $2000 at a hospital — or more.

The foundation’s homes for seniors are especially important since older adults throughout the country are the fastest-growing age group experiencing homelessness, according to an October 2023 report from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. In California, most older adults on the streets had never been homeless before age 50, when life circumstances such as an illness, a work accident or a cut in their work hours cost them their home and left them priced out of the market. In the San Francisco Bay Area, adults over 55 are estimated to make up half of the homeless population.

The co-ed program for seniors started nearly 40 years ago with six beds at Carroll House in San Francisco’s Bernal Heights neighborhood. Shortly after, to keep pace with demand, Rypins House opened with six more beds. As far as Fields knows, they are the only such programs in the country for seniors with dual diagnoses.

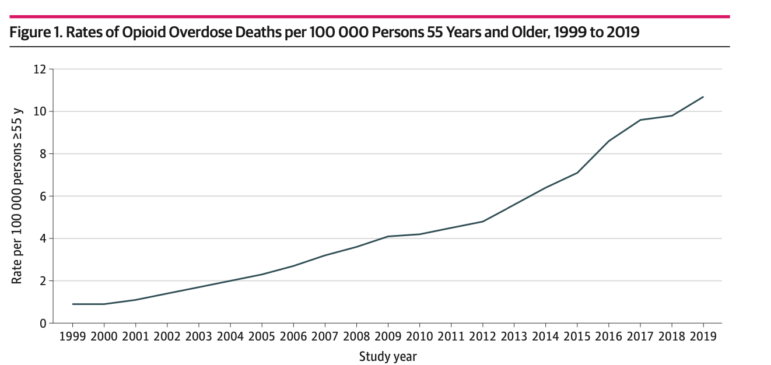

Both are almost always full, and the need continues to grow. In the first 11 months of 2023, an estimated 316 people over 55 died of an overdose in San Francisco, 42% of all the overdose deaths, according to the San Francisco Medical Examiner. Overdose deaths are rising rapidly among older people all across the country.

Progress Foundation takes a harm reduction approach. Clients are encouraged — but not required — to be sober. The location of Carroll House in sleepy Bernal Heights, a place where people can’t easily buy drugs or alcohol, is ideal for sobriety. Keith, for one, hopes to start attending AA meetings again. It’s part of the individualized plan that he’s created with the staff, reflecting a core belief at Progress Foundation that clients take ownership of their recovery.

Celeste Hamilton Dennis / MindSite News

Art on the wall at Rypins House.“We’re there to provide guidance and support,” Roberts says. “We treat the clients themselves as the expert, and collaborate with the individual we’re serving to meet the aims they’ve defined for themselves.”

That doesn’t mean they’re on their own, however — staff members are available 24/7 if clients need them for health problems or other needs.

During the daytime, group meetings take place, tailored to the needs of the clients living in the house at the time. On the Friday I visited, the group met in a cozy living room at Rypins House, surrounded by books and a piano. Led by nurse facilitators from the University of California San Francisco, clients brainstormed ways of getting social support. Keith said he was going to get a library card to read autobiographies, and that he wanted to start playing chess again.

Staff encourage these kinds of activities as a way to develop social connections. They also help clients connect to case management, psychiatry appointments, housing, and more — everything they need to be independent. As part of its contract with San Francisco County, Progress Foundation must help a minimum of 80% of clients to move to a lower, less intensive level of support identified in their treatment plan, a number they have consistently met, says Fields. But it’s complicated.

“Am I happy with all of the choices as time goes on that are available to people? No,” he says. “At least they’re not in the hospital.”

In the past year, only two out of 32 clients from the seniors program were rehospitalized during the course of their stay; the rest were able to make it through and enter one of a variety of housing choices when they left the hospital.

Some of those include traditional apartments, single room occupancy hotels, and board and care homes, which are slowly disappearing. There’s also Hummingbird Place, a psychiatric respite center that will work with clients to find a path to permanent housing after they leave. It’s a huge challenge, given California’s sky-high housing costs, especially for those who don’t have Social Security. And the age of the unhoused is rising in California.

Fields worries that as people move between different programs and facilities, each operated by a different organization, no one person or agency is looking out for people at all stages and taking responsibility for their progress.

“Who’s responsible for John Smith, who may enter the system at the emergency room, go to Progress Foundation’s acute diversion, then Rypins House for six months, and move on to a supportive housing program run by another agency?” he says.

What’s needed, he says, is essentially a system-wide super case manager, who can follow a person through all levels of the system, no matter which program they’re in.

Staff at Rypins and Caroll try to set clients up for success by helping them learn how to navigate living with roommates — odds are, they’ll have to do so in the future for financial reasons.

Rebuilding a life

Andrea Q came to Progress Foundation after living in a single room occupancy hotel in the Tenderloin, where she stopped taking her bipolar disorder and anxiety medications because there was nobody to hold her accountable. “That’s the first thing that went out the window,” she told me.

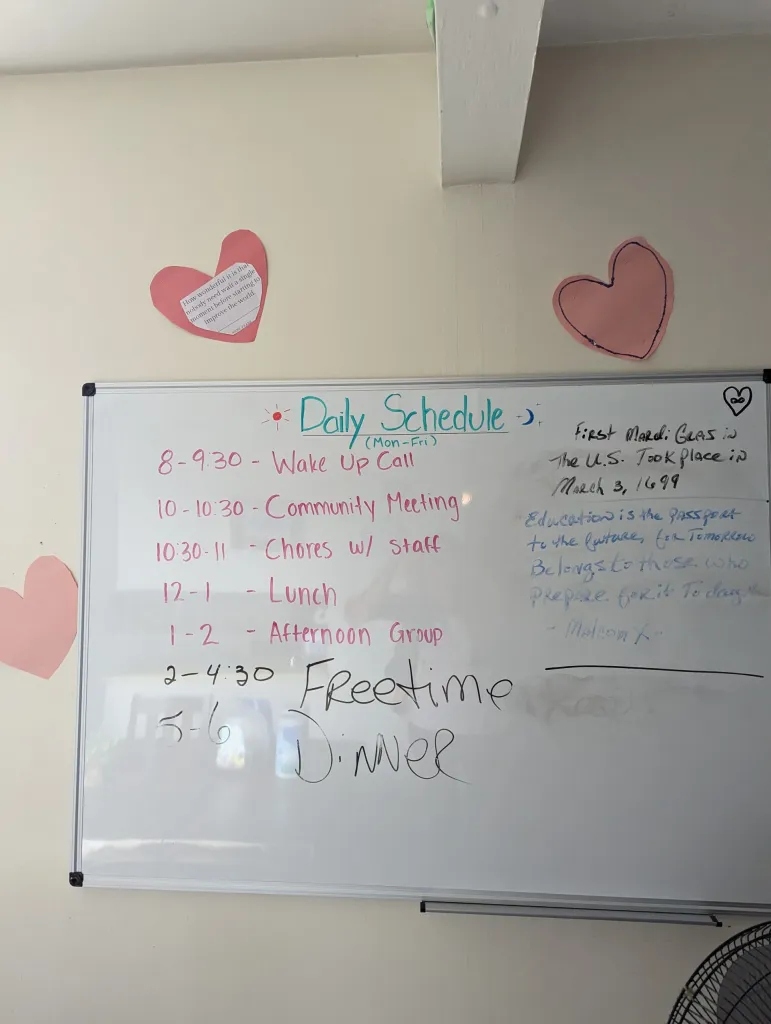

Celeste Hamilton Dennis / MindSite News

The daily schedule at Carroll House.Then the 62-year-old relapsed with her husband, with whom she’s been using substances and off for 30 years. In June last year, she overdosed — and almost died after injecting a combination of Xanax, methadone, and fentanyl. Her heart stopped beating — only to be revived with a shot of Narcan. It was the wake-up call she needed to come to Carroll House.

“We’ve pretty much had it with that life. I can’t tolerate any kind of drugs anymore. It would be like a death sentence,” she says. “I wanted somewhere I have to be held accountable.”

These days, Andrea spends most of her time developing a routine outside the house that she can continue once she leaves — like swimming at a nearby pool and being part of a writing group. She gets Social Security and hopes someday to move with her husband, who’s in another treatment facility, to “a nice place” outside San Francisco.

For now, Andrea likes being around people her own age who won’t mind hearing about her osteoporosis. She enjoys the camaraderie with her roommate the most, an older Latina woman who dyed Andrea’s bob hot pink — and in the process, dyed a patch of her own hair when she touched her temple with a stained hand.

With their matching pink hair, they sat with their housemates on a Friday evening in August to dine on Andrea’s cheese and tomato quesadillas. Eating together builds community and encourages responsibility, and clients take turns making meals. Cooking can be challenging for Andrea, and sometimes provokes anxiety. So she keeps it simple — quesadillas or ravioli.

These two senior homes are in high demand, especially in the spring. When beds open up, program staffers go to hospitals, jails, and other programs to interview potential clients. One thing they let prospective residents know is that staying there means learning to navigate conflict.

Just ask Andrea. One night not long ago, one of her housemates didn’t show up for dinner. He came into the kitchen a bit later and declined Andrea’s offer of a quesadilla. He made a bowl of Ramen instead, and spilled it all over the microwave.

“Are you going to clean it up?” Andrea asked.

“How?” he said. “What do you clean it up with? Water?”

“No, with paper towels,” Andrea said. “You know how to clean up.”

“I’ll do it in a little bit.”

He sat at the table in his flannel shirt and slurped the noodles, saying little. Andrea was irritated, but said nothing more. Then the man took his bowl to the sink, tore off some paper towels, and wiped the microwave clean. Andrea thanked him, a tinge of pride in her voice.

“Good for you,” she said. “Good job.”

Reporting for this story was supported by the California Health Care Foundation and the National Institute for Health Care Management.