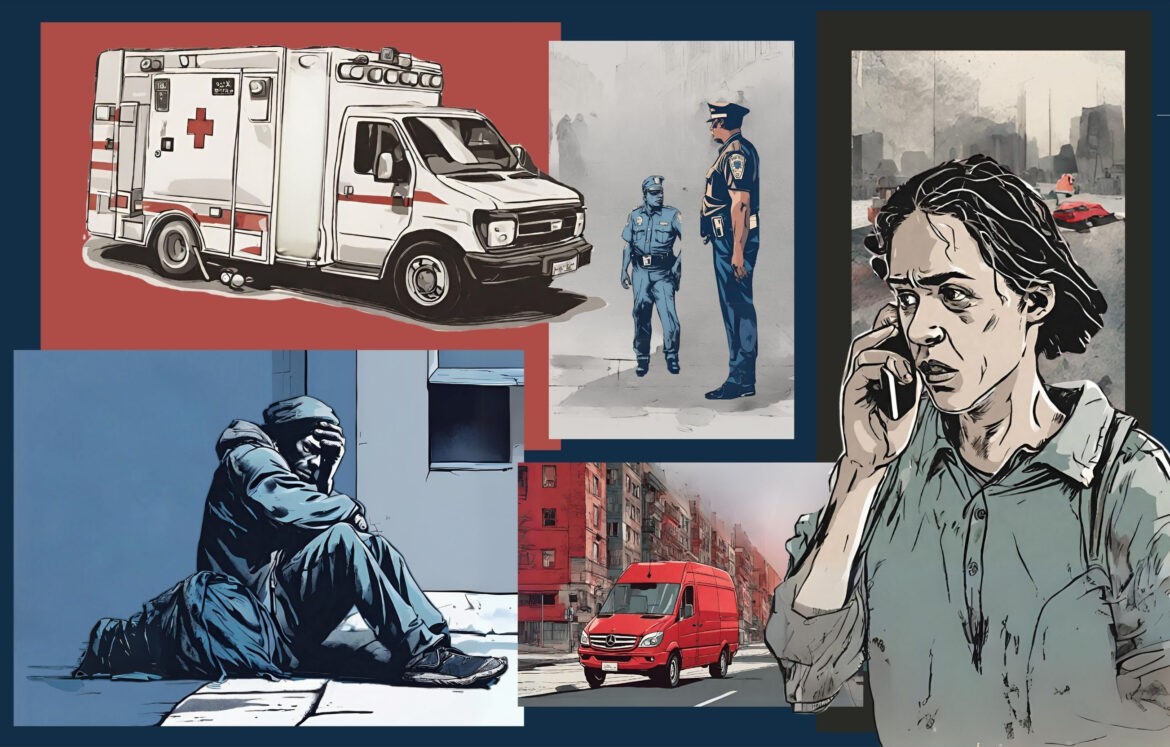

In San Francisco, it is not uncommon to cross paths with a person experiencing homelessness in the throes of a mental health crisis. The scene can be tragic, confusing and sometimes might feel dangerous.

Bystanders might wonder how to summon help from the city — and what will happen if they do.

We created a flow chart to answer those questions, though it does not capture all possible outcomes. Scroll down or click here to find it.

Cases traverse a tangle of pathways, through handoffs between dispatchers and myriad public workers. The person in crisis might spend days or weeks tumbling through the criminal justice system or health care facilities. They might get a reprieve from the outdoors in a sobering center or a communal recovery setting, where they can access food and information to help them seek social services. Their path depends on many factors, like the availability of the Street Crisis Response Team, what the bystander tells city personnel and whether responders can calm them.

Often, the person returns to where they started: the streets.

San Francisco emergency dispatchers can receive tens of thousands of calls per year about mental health incidents, including suicide attempts. According to a recent study by a city working group, there were nearly 13,700 recorded involuntary psychiatric detentions in the fiscal year that ended in 2022 — a conservative tally as the analysis did not include some facilities in San Francisco. The study found that African American residents were detained at disproportionately high rates, and unhoused people were frequent users of psychiatric emergency services.

How San Francisco Handles Mental Health Crisis Calls by Yesica Prado and Madison Alvarado(Click the link below the chart to see a version that allows you to zoom in.)

The San Francisco Public Press spent months investigating how people can be detained involuntarily due to mental health crises and what happens to them afterward. The psychiatric detentions are commonly called “5150” holds, a nod to the section of state code that defines the criteria for this intervention. We examined hundreds of pages of call records, department procedures and training documents, and interviewed staff at numerous city departments directly involved in crisis response to map the city’s system of care.

A single phone call about an incident can trigger responses from multiple departments. Major responders include the Department of Emergency Management, Fire Department, Police Department, Sheriff’s Department, Department of Homelessness and Supportive Housing, and Department of Public Health.

Sign up for our free weekly newsletter so that you catch our follow-ups on this topic

People witnessing a crisis generally request help by calling either 911, the city’s emergency line, or 311, for general services and assistance. Dispatchers do their best with the information the caller provides to quickly determine whether the distressed person poses an immediate danger to themselves or others.

Calls about mental health crises often ping-pong between 911 and 311 as details emerge, said Burt Wilson, president of the union chapter that represents the city’s emergency dispatchers.

Many unhoused people carry weapons to defend themselves at night, and they might struggle with drug addiction or be mentally unstable, Wilson said.

“I don’t know how you differentiate, on the phone call, who to transfer to 311 and who to transfer to the police,” Wilson said. “Most of the 311 calls end up coming back to our call center because 311 just has to say a certain trigger word like, are they ‘aggressive?’ And then it comes right back to us.”

The Department of Emergency Management dispatches police in cases of calls about people threatening violence or wielding weapons; that doesn’t include people who are merely yelling, said Officer Robert Rueca, a spokesperson for the San Francisco Police Department.

But what qualifies as “violence?” The Department of Emergency Management could not say.

“‘Violent’ is not something we have a concise definition for,” a spokesperson said. “It will vary based on circumstances and the level of information the reporting party is providing.”

And a “weapon” is broadly defined as “anything that can be used as a weapon,” according to department guidelines. For many types of small weapons, such as pocket knives, possession alone is not considered a threat.

“The shortage of support and funding is really a challenge. … Without having continued support after being 5150’d, or [receiving] forced treatment, you’re just setting up someone for more failure.”

Mark Salazar, Mental Health Association of San Francisco

If a person is in severe crisis, police and medical personnel can put them on a 5150 hold.

But involuntary hospitalization can be harmful, said Sarah Gregory, a senior attorney at Disability Rights California. The organization advocates for community-based services for people with mental health disabilities, as an alternative to forced stays in hospitals or psychiatric wards.

Gregory called it a “traumatic” experience when someone “who’s already having a mental health crisis calls for help, and then receives a response that takes away the person’s rights.”

“Client after client says, ‘I came out of there worse than I went in,’” Gregory said, referring to places where patients were involuntarily detained.

When a person in mental distress is not an immediate threat, the call goes to medical personnel like the Street Crisis Response Team, Fire Department or paramedics. The crisis team is one of many created in recent years as San Francisco and other cities have shifted away from a law enforcement response following high-profile police killings, including those of Mario Woods, Tony Bui and George Floyd, in which the officer was convicted of murder.

The San Francisco Police Department “would never be dispatched to a medical call” even if the Street Crisis Response Team or an ambulance were unavailable, said the spokesperson for the Department of Emergency Management. The police were the crisis team’s backstop in its early years, but that stopped in June 2022, they said.

The team uses de-escalation strategies to calm a person in distress, like speaking softly, asking questions to get to know them, and offering snacks or water. When the person regains composure, the team might connect them to treatment or follow-up care with the Office of Coordinated Care, Homeless Outreach Team or Post Overdose Engagement Team, the spokesperson said.

The team might also simply leave the scene once the person is no longer in distress.

People who engage with the city’s crisis-response system might benefit most from having long-term case managers who can help them fully resolve problems with their health or living situations, said Mark Salazar, chief executive officer of the Mental Health Association of San Francisco. The organization provides case management and peer support services at courts, jails and Zuckerberg hospital after someone is released from a 5150 hold.

“But the shortage of support and funding is really a challenge,” Salazar said. “Without having continued support after being 5150’d, or [receiving] forced treatment, you’re just setting up someone for more failure.”

Support for people struggling with their mental health

San Franciscans struggling with their mental health can call many local and national hotlines. To learn about the resources that are available, and potentially speak with counselors, reach out to the organizations below.

Mental Health Association of San Francisco: Talk to a peer about your feelings and get information about available mental health services.

- Warm line is open 24/7

- Call or text 855-845-7415

San Francisco Behavioral Health Services: Find local mental health or substance use services that meet your needs.

- Clinicians are only available Monday-Friday from 8 a.m. to 7 p.m., and Saturday-Sunday from 9 a.m. to 4 p.m.

- Behavioral access helpline is open 24/7

- Call 415-255-3737 or 888-246-3333

Harm Reduction Therapy Center: Speak with someone if you are experiencing homelessness and seeking peer counseling or harm reduction services.

- Community helpline is open Monday-Friday, from 10 a.m. to 8 p.m.

- Call 415-863-4282

San Francisco Night Ministry: Speak with counselors trained in trauma-informed care, interfaith spiritual support, suicide prevention and crisis management.

- Care line is open every day from 8 p.m. to 2 a.m.

- Call 844-467-3473

Mobile Crisis Team: Speak with clinicians who can help someone experiencing a crisis. The team may visit the person to assess whether they meet the criteria for involuntary psychiatric detention, and they can request support and transportation by paramedics or police.

- Helpline is open 24/7

- Call 628-217-7000

SF Suicide Prevention Hotline: Speak with a counselor if you or your loved one are considering suicide. Counselors can provide referrals for mental health, HIV and addiction services.

- Hotline is open 24/7

- Call 415-781-0500 or text 415-200-2920

Other resources

California Peer-Run Warm Line

- Warm line is open 24/7

- Call or text 855-600-WARM (9276)

California Suicide Prevention Lifeline

- Hotline is open 24 hours

- Call 988

- Crisis counseling is available 24/7

- Text HOME to 741741

- Visit their website to connect via online chat or WhatsApp

Like many media organizations, the San Francisco Public Press is experimenting with artificial intelligence (A.I.) tools that aid the creation of images for use in some stories. Nearly all our visual content is produced by humans.

The Public Press is part of the Mental Health Parity Collaborative, a group of newsrooms that are covering stories on mental health care access and inequities in the U.S. The partners on this project include The Carter Center, The Center for Public Integrity and newsrooms in select states across the country.

See our related article, The Often Vicious Cycle Through SF’s Strained Mental Health Care and Detention System