This article is adapted from an episode of our podcast “Civic.” Click the audio player below to hear the full story.

Lee esta historia en español.

When Karen Rodriguez arrived in San Francisco after fleeing her home country, Colombia, with her husband and her 6-year-old son, Juan, the family stayed with her son’s godmother. But when they had to leave two months later because the lease didn’t allow for extra people in the unit, they resorted to sleeping in their car.

Because the family was newly arrived, Rodriguez and her husband did not have work authorization, making securing jobs and paying rent extremely difficult.

They have since been bouncing between stays in their car and stays in hotels paid for by the city and Faith in Action Bay Area, a network of community organizers from various faith congregations. Juan has special needs, so an emergency shelter would be traumatic for him, Rodriguez said.

The Rodriguez family is among many recent migrants seeking shelter and a new life in San Francisco, who are falling into homelessness with no easy way to climb out.

San Francisco housing providers, legal advocates, faith groups and migrants themselves warn that there is not enough temporary housing to accommodate the increased need, and that the city’s response system is not equipped to handle the complications that arise at the intersection of homelessness and immigration. Housing providers say also that the city is intentionally under-counting and under-representing the need.

While city representatives said the Department of Homelessness and Supportive Housing is taking steps to reallocate funds to open a family shelter and quicken the rate at which families move out of shelter and into longer term housing, they were unable to provide a timeline or instructions as to what families sleeping on the street should do in the meantime.

‘Profound’ need and poor data

The notion that there isn’t enough temporary housing for these families conflicts with the city’s shelter inventory, an online dashboard that tends to show family shelter vacancies around 7% or 8%. But Hope Kamer, director of public policy and external affairs at Compass Family Services, a nonprofit focusing on family homelessness, said this is not a true reflection of the need.

“Families are coming to our access point at 4:30 on a Friday and saying, ‘I have nowhere to go for the weekend with my two infants,’” she said, calling the need “profound.”

Often, families are turned away for lack of shelter slots.

That happened to Álvaro Tovar and his wife and two young children when they recently showed up at a shelter access point, where families are assessed for service eligibility, he said. Staff told him that it would take two weeks before he could put their names on the waitlist, and longer to get beds. They advised him to buy a tent for his family to stay in while they waited.

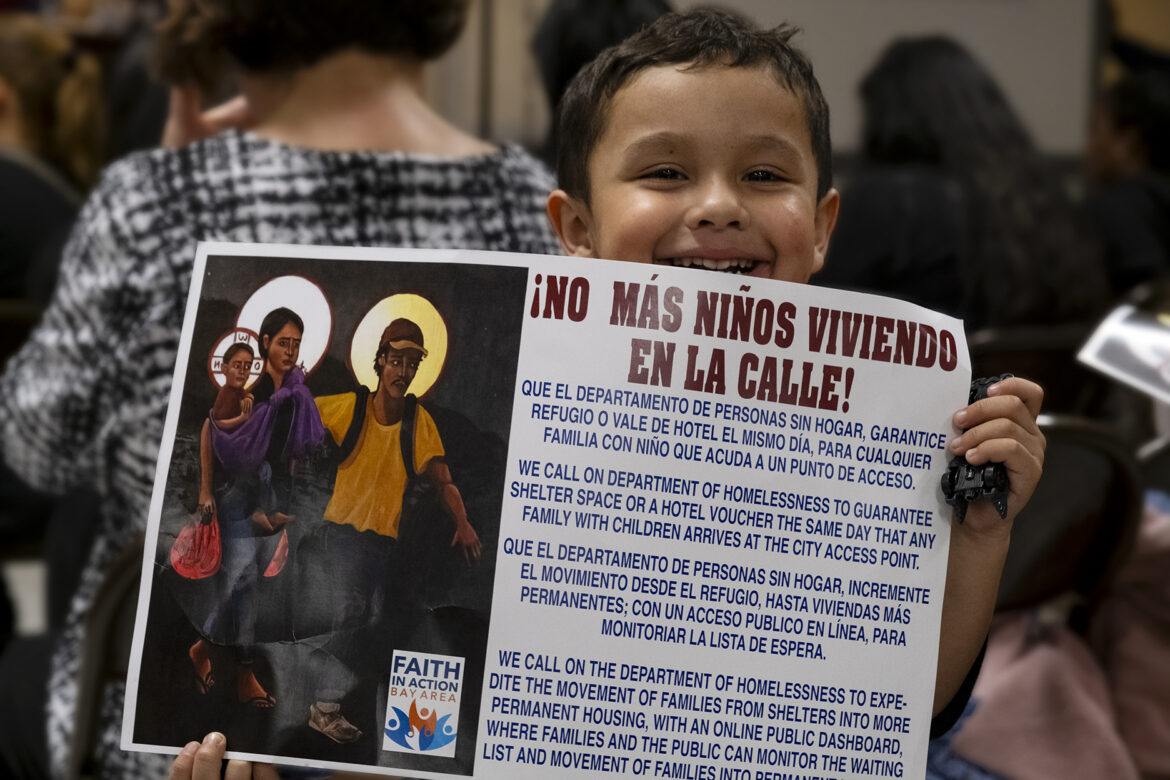

“That broke my heart because first of all, we didn’t have any money, we didn’t know the city. I lost all hope,” Tovar said at a March 7 community event that Faith in Action Bay Area hosted to bring attention to the need for family shelter.

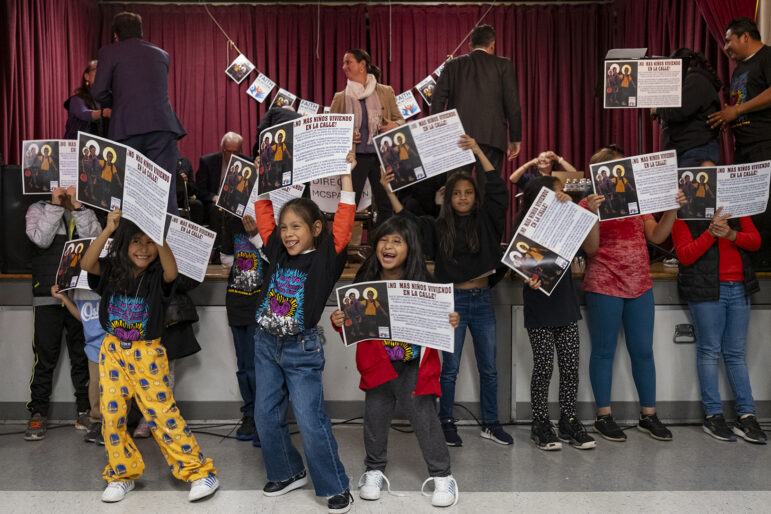

Yesica Prado / San Francisco Public Press

At the March 7 community event to urge San Francisco legislators to provide additional shelters for unhoused immigrant families, dozens of children eagerly rush to the stage at St. Anthony’s Catholic Church in the Mission District. The children raise signs asking the Department of Homelessness and Supportive Housing to guarantee applicants a shelter space or voucher to stay at a hotel.Kamer said the Buena Vista Horace Mann Shelter, a school gym that functions as a family shelter at night, gets as many as 10 calls a day from community-based organizations searching for beds for families who have nowhere to stay, many of whom the shelter can’t take in.

Laura Valdéz, executive director of Dolores Street Community Services, the nonprofit that runs the Buena Vista Horace Mann family shelter, told the San Francisco Standard in December that the city instructs the organization to not count the number of families it turns away.

Emily Cohen, deputy director for communications and legislative affairs at the Department of Homelessness and Supportive Housing, said she wasn’t aware of that instruction. Rather, she said, the department wants people to go to entry points for the homeless response system to create one centralized shelter waitlist.

Over the past six months, that waitlist has consistently contained some 200 families, Kamer said. At Buena Vista Horace Mann, the department counts the shelter occupancy at 5 p.m., before parents have returned from their jobs and thus under-representing the need, she said.

“This unwillingness to capture the full scale of the problem means that there is not accountability to these families and there is, in turn, not public pressure to build the amount of shelter stock we need,” she said.

Migrant families themselves have been banding together to create that pressure. Partnering with Faith in Action Bay Area, the families have issued demands to the Department of Homelessness and Supportive Housing: guarantee same-day shelter or a hotel voucher for any family who goes to an access point; expedite the transition from shelter to long-term housing; and create an online dashboard that lets families check their position on a shelter waitlist.

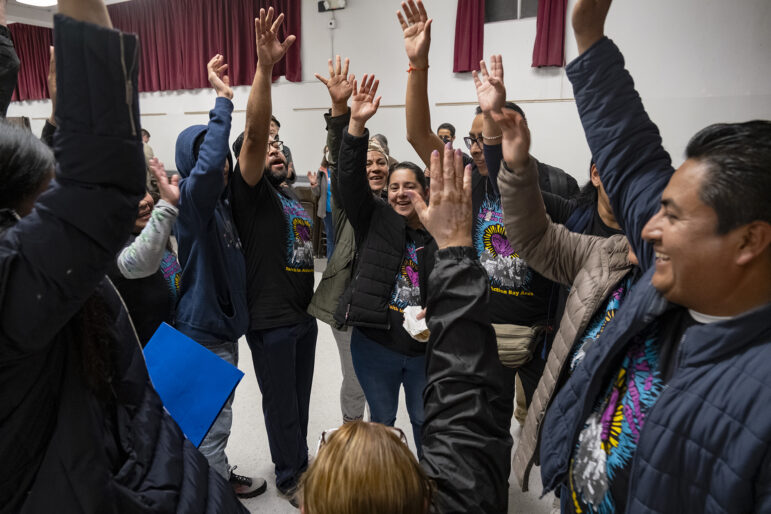

Yesica Prado / San Francisco Public Press

After the March community event, many immigrant families from Latin American countries gather to discuss their advocacy work, aimed at garnering support from local legislators for housing initiatives. They form a circle, cheering for their collective efforts.The group held a rally outside City Hall on March 12, the day supervisor and declared mayoral candidate Ahsha Safaí introduced a non-binding resolution calling on Mayor London Breed and the Department of Homelessness and Supportive Housing to respond to migrant families’ housing needs. The full Board of Supervisors will hold a hearing on the resolution on April 22, according to staff from Faith in Action Bay Area.

Other barriers to safe housing

Besides lack of shelter beds, migrant families face other issues as they try to navigate the system.

“For many families, the homeless response system in San Francisco is their first touch point for social services in the United States, and the system is fundamentally not resourced to do the legal navigation and trauma-informed care that a family that has just made an immigration journey to San Francisco needs,” Kamer said.

Vanessa Bohm is the director of the Family Wellness and Health Promotion programs at the Central American Resource Center, a nonprofit that helps Latinx migrants and under-resourced families in the San Francisco Bay Area. She said that 15 or 20 years ago, it was easier for people to get rooms or jobs through the informal economy or through connections to people they knew here. Today, she’s not sure that is the case, she said.

Silvia Ramos, a senior case manager and support group facilitator for the family wellness program at the Central American Resource Center, said many families arrive in San Francisco with trauma from their journey and feel displaced as they enter a system that is difficult to adapt to. When families show up with nowhere to stay and the city has no beds, she will look for beds in Oakland or other nearby cities and teach people how to use Bay Area Rapid Transit.

Navigating these systems can be even more difficult for people who don’t speak English, or who come from different cultural backgrounds, many providers said.

Role of immigration court

While trying to access housing, families must also worry about the asylum process and immigration court system. However, providers noted disconnects among the legal and homeless response systems, and groups that offer other resources like medical care or food.

“There is no government help coming to connect the legal response system and the homeless response system,” Kamer said. “The direct care providers are figuring out how to do that.”

Milli Atkinson, director of the Immigrant Legal Defense Program at the Justice and Diversity Center of the Bar Association of San Francisco, said most people’s asylum cases aren’t decided for years and they often worry more about immediate needs like housing or food.

“A lot of people get lost in the system, just because they don’t have the capacity mentally to figure all of these things out at once, and they’re going for their basic needs first,” she said.

But having legal representation during the asylum process helps migrants get work authorization, enabling them to become more self-sufficient.

Housing instability can affect immigration cases in other ways. One of the biggest hurdles for people experiencing homelessness, Atkinson said, is that the court system relies heavily on paper and communication is primarily done through the mail. People are expected to keep the court updated on their addresses.

“If the court mails you things about your case, and you don’t get them, it’s your fault,” she said.

Influx of migrants

Housing providers, legal advocates, and the Department of Homelessness and Supportive Housing anecdotally noted an increase in the number of people seeking services who are fleeing Latin America due to political unrest, poverty and other violence.

Atkinson said that in recent years her organization has seen a greater number of migrants from countries like Nicaragua, Colombia, Peru and Cuba. As the number of countries experiencing political instability in recent years has risen, the number of people seen coming in at the border has also gone up, she said.

Because San Francisco is a sanctuary city, questions about immigration or refugee status during the coordinated entry process, a system used to determine what type of resources people qualify for, are limited. This makes it difficult to say what percent of the recent surge of families seeking shelter are migrants, Cohen said, though she anecdotally noted that there have been more people from Central and South America asking for assistance.

City data shows that the share of Spanish-speakers and Latinx people experiencing homelessness is increasing. The share of Spanish-speakers in the city’s ONE System, which tracks people receiving assistance from the Department of Homelessness and Supportive Housing, increased to over one-quarter of the department’s client population in 2024. Additionally, from 2019 to 2022, there was a 55% increase in the number of Latinx people experiencing homelessness, according to data collected during the 2022 point in-time count, a biennial count of the number of people experiencing homelessness.

Yesica Prado / San Francisco Public Press

Unhoused immigrant families rally outside San Francisco City Hall in support of Supervisor Ahsha Safaí’s resolution, which urges the city to ensure that families can access shelter and more easily transition from temporary to permanent housing. Safaí and Supervisor Dean Preston, left, stand in solidarity.Leslie’s story

Safe, stable housing enables migrant families to thrive.

Leslie, who asked to keep her last name private, fled Nicaragua in November 2019 with her daughter and her partner as the country faced increased political violence and she and her partner lost their jobs.

“There was a war and a lot of people were killed. There was chaos everywhere and the economy was already in bad shape,” she said, noting they had no food. “So we left it looking for a better future.”

When they arrived, Leslie faced abuse from relatives she was staying with and was forced to keep her daughter, who is autistic, in her room to shield her from harassment.

“I felt a lot of frustration, a lot of desperation, not knowing what to do,” she said.

Eventually, Leslie, along with her partner and daughter, left. They changed addresses at least three times, moving from a shelter to a friend’s house to a city-funded hotel. It was there, where she was no longer sleeping on the floor, that she began to feel some comfort. She started seeing a therapist and getting medical care, and learned how to get her daughter into school.

But she didn’t know how long they would be able to stay, which caused her anxiety, and there were other problems.

Therapy “opened up my eyes to the abuse that I was suffering at the hands of my partner, so I decided to leave him,” she said. “I didn’t have any family here and I didn’t have any friends. I just had my daughter.”

With the help of Compass Family Services and prenatal homelessness services, Leslie was eventually able to apply for permanent housing for her and her 7-year-old daughter. They moved in in September 2023.

“Now that we have found stable housing, she feels safe, we feel safe,” she said, noting the stability is good for her daughter.

The security has allowed Leslie to pursue an internship teaching preschoolers and sit on Compass Family Services’ Family Advisory Council to share her experiences about navigating homelessness in San Francisco. Going back to school has made her feel useful.

“It makes me feel like I have a better future here,” she said, noting that she wasn’t sure if she would be cleaning toilets for the rest of her life in the United States. “It really fills me up with life and I love to be with the children, and I love to learn.”

Madison Alvarado reported this story while participating in the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism’s 2023 Data Fellowship, which provided training, mentoring and funding to support this project.

Andrea Valencia of Linguaficient, a company that provides professional language services, interpreted our interview with Leslie, a monolingual Spanish speaker. Yesica Prado, a journalist at the San Francisco Public Press, interpreted our interview with Karen Rodriguez.