In February 2021, a tenant in a Tenderloin subsidized housing complex for seniors and disabled people phoned the Department of Building Inspection with an urgent message: Her toilet had been leaking for four or five days. The plumber had told her not to use it for 24 hours, but the repairs were still not working.

Until it was fixed, her only option was to descend nine flights of stairs to use the lobby restroom. But being elderly and diabetic, she sometimes could not make it that far and had no choice but to urinate in her bathtub.

A “known defect” in the building’s toilets led to a backlog of as many as six toilets at a time, the complaint said. She expressed doubts that the Tenderloin Neighborhood Development Center and Glide Community Foundation — which had taken control of the facility from the city after making major renovations — intended to fix it, based on how long they were taking.

“Its known that mgmt will leave tenants with leaks and broken toilets,” the raw notes from the complaint read. “Mgmt said they cant do anything about it.”

The filing was one of hundreds in a crescendo of post-renovation building inspection complaints, many resulting in citations for code violations, across the 29 former public housing buildings that San Francisco handed over to new owners in 2015 and 2016.

Under a federal program known as Rental Assistance Demonstration, nonprofit and for-profit property managers performed direly needed repairs and partnered with onsite service agencies. The conversion infused nearly $800 million into the degrading buildings for repairs, which include about 3,500 government-subsidized apartments.

The privatization process also opened new pathways for residents to learn about their rights, with tenant-support groups reaching out to educate them about how to submit complaints to city departments.

During the conversion, tenants armed with knowledge about regulations became more vigilant about problems, flagging poor management responsiveness to the lack of heat or hot water, plumbing malfunctions and nonfunctional appliances. Tenants have also been filing more grievances about negligent managers than before the system was privatized.

[Read more in our ongoing series, Public Housing in Private Hands]

Complaints and code violations issued by the Department of Building Inspection rose sharply during construction, as might be expected. But they remained high after the renovations concluded, a Public Press analysis of city records shows.

We calculated a rate of complaints and violations per year by adjusting for the number of apartments at each site. Then we compared these rates for the periods before and after construction, accounting for the buildings’ different repair timelines.

Overall, the rate of complaints rose by 156% from pre- to post-construction, while the rate of cited violations rose by 251%, according to building inspection data from January 2000 to February 2023. But building conditions were just one area of conflict. Tenant advocates said they worried that under private management, residents faced increased chances of eviction — except during a slow period due to pandemic-era moratoriums. Precise figures are unavailable because the city did not track evictions in these properties before the conversions.

There are also many stories of rocky relations with new management at some properties: threatening messages, personal confrontations, ignored requests for help.

“It has changed a lot,” said Nina, a tenant in a Mission District subsidized housing facility, describing the transition to new management. Nina lives in a community for seniors and people with disabilities, located at 3850 18th St., with her life partner Ernesto. They requested their last names not be shared due to fear of harassment.

“Why do we have to hide in our room and walk down the hallway and hope we don’t see them?” said Nina, who described numerous instances of harassment by building management and even another tenant who she said had communicated with onsite staff. “We all have our own illnesses and anxiety, and it stresses us out.”

The site is run by Bridge Housing and the Mission Economic Development Agency, nonprofit organizations that took over management of the site from its longtime owner, the San Francisco Housing Authority.

Rose Dennis / San Francisco Housing Authority / 2012 file photo

Housing Authority Director Henry Alvarez lost his job in 2013 after allegations of discrimination against employees, financial mismanagement and poor living conditions. The scandals led city leaders to push for the privatization of thousands of public housing units.San Francisco was one of the first cities in the country to convert a large portion of its public housing stock to private control. Conditions were so bad when operated by Housing Authority staff that leaders knew they had to do something. In 2012, the federal Department of Housing and Urban Development labeled the San Francisco Housing Authority “troubled.” Mismanagement led to the firing of the agency’s director and most of its city-appointed commissioners in 2013.

HUD has declared Rental Assistance Demonstration a success nationally, authorizing more units to be converted and noting that the program has leveraged large sums of private funding to address the substantial repair backlog. It is hard to make direct comparisons with conditions under their former status as government-managed public housing because officials use different scoring systems.

Local inspection records, however, reveal a rising chorus of dissatisfaction.

Complaints to inspectors totaled 607 in the era before conversion (15 to 16 years, depending on the site), but 320 in just the few short years following renovations (2.5 to 4.5 years).

The nonprofit organization Mercy Housing saw the biggest change, with a 256% increase in complaints per year on sites it managed. The runners-up were the for-profit John Stewart Company, with a 189% increase, and nonprofit Tenderloin Neighborhood Community Development Center, at 160%.

There were 223 cited violations before conversion, and 162 after. The two entities experiencing the steepest increase in the rate of violations were Bridge Housing, at 950%, and Mercy Housing, at 549%. Bridge partnered with the Mission Economic Development Agency at five sites and Bernal Heights Neighborhood Center for the redevelopment of two sites.

In an emailed response to these findings, Rosalyn Sternberg, a spokesperson for Mercy Housing, said the conversion “led to significant, tangible improvements” at the organization’s four sites, including physical rehabilitation, onsite staff presence and meetings with residents during the conversion process. The rise in complaints may have resulted from more effective communication among building owners, city agencies and tenants.

Bridge Housing “works diligently to maintain a high standard of maintenance and upkeep at our properties,” wrote Jet Doye, a spokesperson for the organization, noting the millions of dollars it has spent addressing structural challenges and deferred maintenance. Doye said building code violations across Bridge’s seven facilities averaged fewer than one per month since 2015, and every inspection issue has been resolved. Some violations stem from multiple instances of the same problem, so are easily addressed by management.

Complaints and repairs

It is normal for buildings to get written up as they degrade over time, said Lydia Ely, deputy director of housing at the Mayor’s Office of Housing and Community Development. “The key is how long those requests sit, how responsive the owners are and how much trust do people have in their landlords to fix things when they break,” she said. “Things really have improved significantly, but it’s a work in progress like all of the work that we do.”

To explain why rates of complaints and violations were higher today, mayor’s office staff said building inspectors did not regularly visit the sites before their transition from public housing to the Rental Assistance Demonstration program.

They also cited high turnover in management, though they said this was improving. Helen Hale, director of Residential and Community Services at the mayor’s office, said an increase in violation and complaint rates at these sites was unsurprising, but “what becomes concerning would be if they were not responding.”

Most complaints and violations in the dataset were not active, meaning the Department of Building Inspection had closed the cases because the issues were resolved or because no violations were found. However, complaints from residents in 16 buildings noted that management and maintenance crews had not addressed issues in their units in a timely matter, or at all. This pattern echoes the apparent neglect under Housing Authority control a decade ago.

One complaint from a tenant, whose name was redacted, told of a clogged toilet and feces burbling up through the bathtub for four days.

“This is affecting my health,” the complainant wrote. “I am getting sick and throwing up. Management are not responding I need assistance.”

Nina and Ernesto, the two tenants at 3850 18th St., also described a lack of responsiveness. Nina said that Ernesto has been forced to do his own repairs because management had dismissed or failed to adequately address problems.

But maintenance problems weren’t the only issues they faced. As they gathered with family for Thanksgiving in 2021, they heard loud banging on the front door. It was the building manager, who demanded to speak to Ernesto. Nina said she began filming the encounter when the manager became belligerent, threatening to “86” her and then storming off.

“It kind of made us all cry,” she said. The manager was later moved to a new building, but Nina said that despite calls expressing her distress, she never got an explanation or apology from the groups that own the building.

Doye of Bridge Housing disputed these allegations, but declined to comment on specifics. The Mission Economic Development Agency did not respond to requests for comment.

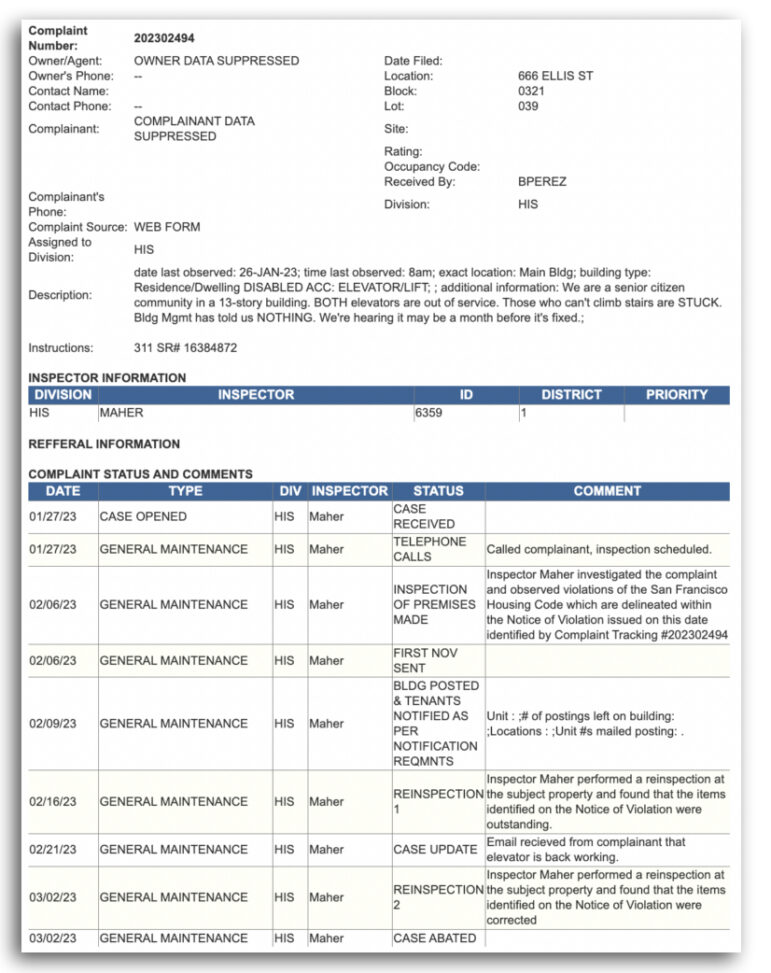

Another complaint noted that both elevators in a building for seniors and people with disabilities were in disrepair and management was not communicating.

Department of Building Inspection

Residents at subsidized housing properties turned over to private owners have increasingly been complaining of poor communication with management, especially regarding the timeline of repairs.Mayor’s office staff said they expect building management to be in communication with tenants, and they connect parties when they receive complaints.

Vulnerability to eviction

Despite the necessity of rehabilitating sites, some advocates said they feared tenants were more likely to be evicted under Rental Assistance Demonstration than under the old locally run public housing paradigm.

Fred Sherburn-Zimmer, executive director of the San Francisco Housing Rights Committee, said the Housing Authority had poor record keeping, and did not typically pursue evictions against people who were behind on rent. She said the small nonprofits that now run some of these sites need the money to fund repairs and social services, leading to evictions for nonpayment of rent and other causes.

Mission Local reported that despite the economic vulnerability of tenant populations, tenants in nearly 14,000 affordable units in city-owned multifamily properties received eviction notices between early 2016 and late 2020. Management companies in recent years have used eviction threats to impose “behavioral stipulations” such as not fighting with other tenants or playing loud music at night, according to advocates.

The city maintains that evictions in the renovated properties are fewer than 1% of households per year. Data from annual reports from the Mayor’s Office of Housing and Community Development shows 91 evictions at Rental Assistance Demonstration sites between initial conversion and December 2019. Hale said residents typically were evicted due to violence or other “cause action,” a reference to the city’s Just Cause Ordinance.

Evictions citywide slowed during a federal pandemic-era moratorium and state-level protections. Only four evictions were documented at these sites between January and December 2020. Data from more recent years was not available.

Covid-19 led many tenants to lose jobs or other income, so many were granted repayment plans or financial assistance. Data shows that between initial conversion and December 2019, 804 households were on repayment plans. Between January and December 2020, there were 109.

“Rent is not a reason to necessarily evict somebody unless you’ve exhausted all opportunity, because what we want to do here is give people a chance to be successful at maintaining their housing,” Hale said.

Heightened tensions

But eviction notices were not the only reflection of a changing relationship with management. The transition to new management has been difficult for some tenants, who described their living experiences as prison-like, claiming the new system was an example of criminalization of being poor, criticism leveled at public agencies across the country.

Establishing a trend across all 29 sites is difficult. Tenants at one site detailed constant surveillance by the housing provider, as well as restrictive rules around who can visit. Some cited feelings of harassment from repeated notices for minor “lease violations” such as momentarily letting a service dog off leash.

Several complaints across the 29 sites alleged harassment, targeted retaliation or eviction threats from building management. Some tenants and advocates described a patronizing dynamic linked to inherent bias related to the demographics of those who lived there. In 2019, 89% of public housing units in San Francisco had a head-of-household who identified as an ethnic minority.

“We’re so patronizing towards tenants who live in public housing,” Sherburn-Zimmer said. “We treat it like they don’t deserve fair housing, decent housing, that they shouldn’t have a say-so in their house in basic decisions that affect their lives. Ultimately, over and over, I think this is because of racism.”

One tenant named Johnny Rudolph said he often joked with the building manager, calling her “warden.” She called him “inmate.”

Other tenants in interviews or in complaints submitted to the Department of Building Inspection said they did not receive reasonable accommodations for disabilities or conditions described in doctor’s notes.

Some tenants pointed to a lack of responsiveness from the Housing Authority and the inability of tenants’ rights groups to act before a formal eviction process has begun.

In response to questions about such critiques, the Housing Authority emailed a statement not attributed to an individual there that the properties’ day-to-day operations “are solely the obligations of the nonprofit affiliated developer owners” and that the agency’s role is to provide rental subsidies and ensure lease compliance with the developer that runs the site.

The email noted that the agency addresses tenant concerns brought to its attention at the Housing Authority Board of Commissioners meeting, by facilitating meetings with owners, service providers and the mayor’s office.

Educated tenants

The transition to Rental Assistance Demonstration did keep its promise to rehabilitate deteriorating conditions — and increased tenant knowledge in the process.

“The buildings were in horrendous shape” before conversion, Sherburn-Zimmer said, citing lack of federal funds and incompetence at the Housing Authority. Agreeing with this assessment regarding the financial situation, the Housing Authority said in its statement that it aimed to ensure “safe, decent and sanitary housing” and social services for tenants.

During the transition, the city worked with the Housing Rights Committee and Bay Area Legal Aid to educate tenants on their rights, including the ability to submit complaints and receive city inspections.

Hale also said tenants who had not paid rent for years after objecting to unaddressed poor living conditions had to adjust to paying again. That resulted in much higher rates of collections. Tenants also needed to be educated on the complaint process with each building’s management and reasonable timeframes for addressing repairs.

In Sherburn-Zimmer’s experience, property management makes repairs in most situations, though some respond to maintenance requests slowly, especially in the wake of the pandemic. In recent years, the Housing Rights Committee has not had the funding to place organizers in every property, making it hard to keep track of issues in detail.

All agree that the 29 public housing sites were deteriorating before renovations — a problem in San Francisco’s remaining public housing that persists today. Tenants at Plaza East Apartments, a public housing complex demolished and rebuilt in 2001, continue to face distressing living conditions. Managers at Potrero Terrace-Annex, another former public housing site in Potrero Hill undergoing demolition, received a failing scorecard from the Housing Authority in January and February 2023 for failure to address life-threatening maintenance issues in a timely manner and other problems.

An unprecedented plan

Mayor Ed Lee initiated the transition to private ownership in a July 2013 plan to re-envision public housing across the city, citing $270 million in deferred maintenance. Nationwide, the public housing repairs backlog is estimated to be as much as $70 billion due to declining funds over several decades. The Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, a think tank that analyzes government budgets, found that funding for repairs fell by 35% between 2000 and 2018.

Many of the renovated San Francisco sites had received failing inspection scores from HUD for years. In 2012, it gave the Housing Authority a score of 54 out of 100 on an assessment of its physical and financial condition, making it one of two housing authorities statewide to receive such a low rating.

Many residents and advocates were initially wary of the program. At the heart of residents’ fears around the privatization scheme was fear of displacement, and for good reason. Under a 1990s federal program meant to rebuild public housing using private funds, the city demolished buildings and rebuilt several hundred units fewer, forcing out tenants.

To avoid repeating this mistake, the city renovated the first two phases of Rental Assistance Demonstration buildings in parts instead of wholesale demolishing them, temporarily relocating tenants until fixes were complete.

Overall, the city estimated that the total value of the real estate deal was $2 billion. This includes $800 million in loans owed to the Housing Authority. Bank of America Merrill Lynch and Aegon provided $816 million in financing in exchange for interest and various tax benefits. The Federal Home Loan Mortgage Corporation lent $332 million, and the city of San Francisco lent $100 million.

Under the new program, the land underneath the buildings remains in the hands of the San Francisco Housing Authority, which leases it out for 99 years to maintain affordability.

Today, more housing authorities across the country are using Rental Assistance Demonstration to complete repairs, with more than 170,000 units converted, and almost $17.8 billion spent in construction investment. An additional 180,000 are in the process of being converted.

“The effort to preserve public housing and create new affordable units has long been hindered by tight federal budgets and scarce city and state funding,” then-HUD Secretary Julián Castro said of San Francisco’s renovations back in 2013. Rental Assistance Demonstration, he predicted, “will spur millions in private investment to address long overdue capital repairs, spark economic development, enhance this city’s urban life and secure its affordable housing future.”

While HUD’s rosy assessment turned out at least partially true, tenants’ accounts and the record of building code violations show how rocky the road has been.

Additional reporting by Jordyn Gleaton.

This article is supported by a grant from the Fund for Investigative Journalism.