Ideas for reparations in San Francisco go far beyond a proposed $5 million payment to each qualifying Black resident — the option that captured national media attention and inspired a handwringing frenzy. The Board of Supervisors will review and discuss dozens of policy recommendations when it meets March 14 to weigh in on the city’s draft reparations plan.

[Note: @MadisonAlvarad0 (that 0 is a zero) is planning to live tweet from Tuesday’s meeting]

The proposals are non-binding, with the committee noting in the plan that “it will be up to the community to create the momentum to ultimately get these recommendations officially codified into San Francisco law.”

The committee will submit a final version to the Board of Supervisors in June, but a flurry of headlines, including ones from CNN, Fox News and the Weekend Update segment on “Saturday Night Live,” latched onto the $5 million figure when the committee released a draft of its reparations plan in January.

Several supervisors have already weighed in on the possibility of such payments. Supervisor Dean Preston, who represents the Western Addition, Tenderloin, Haight Ashbury and Japantown, and Supervisor Shamann Walton, who represents Bayview-Hunters Point, Potrero Hill and Vistacion Valley, said cash payments were possible. Two others — Supervisor Joel Engardio, who represents the Outer Sunset, and Supervisor Hillary Ronen, who represents the Mission, Portola and Bernal Heights — said they were likely infeasible.

The plan outlines a range of possible action under four umbrellas: economic empowerment, education, health and policy. It also delves into the lengthy historical record of harms committed against Black people in San Francisco.

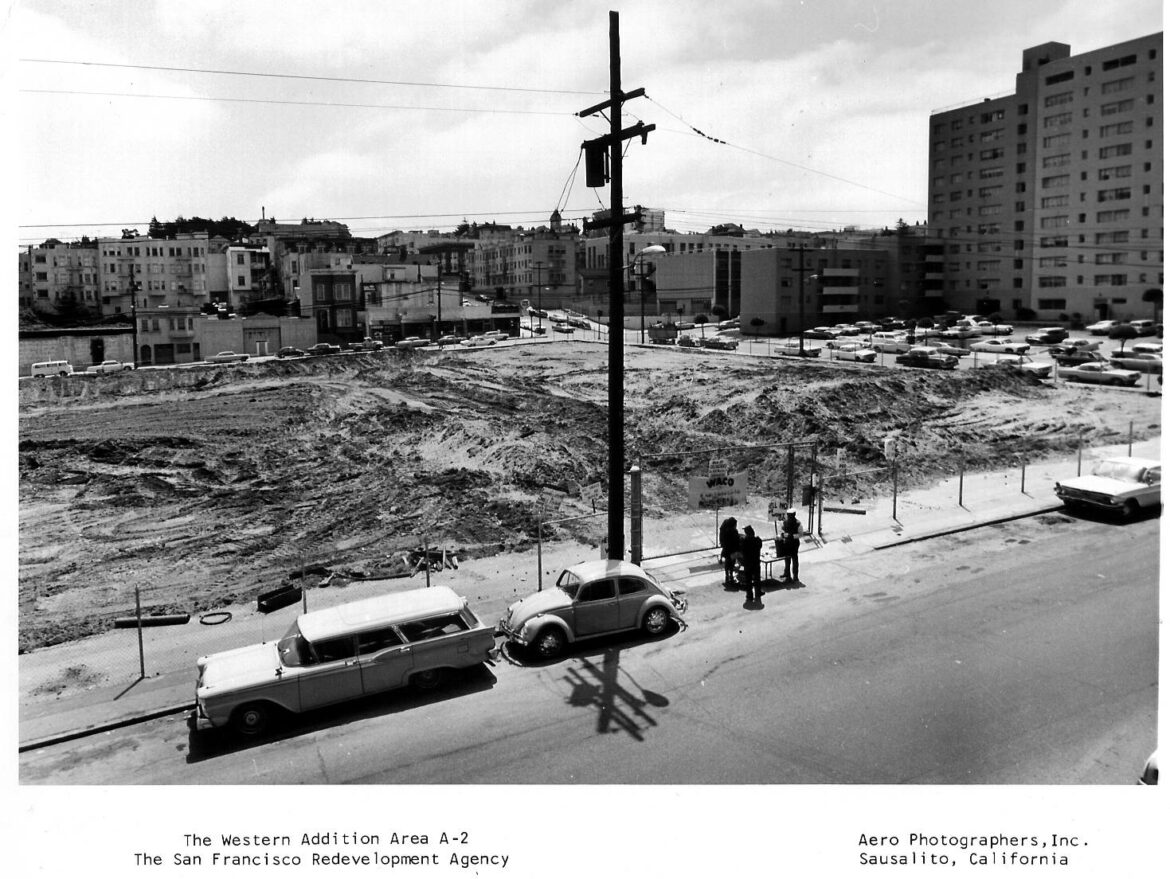

Beyond seeking compensation for the atrocities of slavery, segregation and racial terror, the plan calls for corrective action for harm caused by housing policies, particularly the displacement of thousands of African Americans from the mid- to late-20th century under a program known as urban renewal. The plan identifies other policies that divested Black communities of their rights, homes and ability to build generational wealth, including racist lending practices known as redlining (which de facto prohibited African Americans from obtaining loans to purchase homes), racially restrictive covenants that prevented Black people from renting or owning certain housing, race-based zoning laws that stopped them from living in certain neighborhoods, and segregated public housing.

The plan includes solutions addressing homelessness and housing affordability. Today, Black San Franciscans represent 38% of the unhoused population even though they represent only 5.3% of residents. They also have the lowest rate of homeownership citywide.

“A hope of the African American Reparations Advisory Committee is that this document would serve as an actionable tool for communities for advocacy, and really a road map for lawmakers,” said San Francisco Human Rights Commission Economic Rights Director Brittni Chicuata, who also manages the reparations advisory committee.

“Most of the folks I’ve talked to have only focused on the $5 million recommendation,” Walton told The San Francisco Standard. “I’m trying to get everyone to focus on the fact that the task force is taking this work seriously and came together with recommendations that we need to look at.”

Housing action items

The plan’s current objective regarding housing reads: “Ensure that all members of the affected community have access to affordable, quality housing options at all income levels,” and focuses on living situations that include home ownership, rentals on the private market, subsidized rentals and public housing. To help tackle ongoing disparities and rectify past harms, the plan offers these housing-related suggestions for those qualifying for reparations:

- Removing qualification barriers for subsidized rental units, and offering first choice to those who qualify for reparations. The plan also recommends that the city subsidize those who cannot afford a unit’s full cost.

- Guaranteeing funding for the Dream Keeper Down Payment Assistance Loan Program, which provides down payment loans for first-time home buyers in San Francisco.

- Changing Dream Keeper program loans into forgivable grants for those owed reparations, regardless of their income.

- Amending the below-market-rate ownership program to help participants build wealth. Currently, participants cannot pass along units to descendants or rent out properties.

- Creating pathways for public housing residents to own units by converting public housing into condominiums with a $1 buy-in for current qualifying tenants.

- Establishing and funding a Black-led community land trust, a type of nonprofit that owns and stewards land on behalf of a community, providing long-term affordable housing and assets like gardens or small businesses.

- Requiring building owners to make residential units that are vacant for three months or longer available for rent or purchase by people who qualify for reparations, and by Black holders of Section 8 vouchers or certificates of preference.

- Offering grants for home maintenance and repair costs for those who qualify for reparations.

- Paying extra housing-related monthly costs in new buildings that might otherwise act as affordability barriers for people who qualify for reparations, such as parking fees.

- Fast-tracking permit approval and providing other support for developers building below-market-rate housing.

- Creating new benefits for housing choice voucher holders under Section 8, a federal program for low-income people who pay 30% of their income for a private unit, with the government subsidizing remaining rent. Suggestions include giving voucher holders first right of refusal to any housing opportunities in the city and offering financial assistance to help with moving costs.

- Changing regulations regarding certificates of preference to offer further benefits to certificate holders, outlined in our previous coverage.

- Underwriting expenses that come with refinancing mortgage loans.

Some suggestions in the reparations plan may be difficult to implement given legal prohibition of racial discrimination in housing opportunities.

“I think we need to be more bold and take more risks and really be intentional in how we address inequities around race,” Walton said in a December interview about the city’s eight-year housing plan. Citing ongoing displacement of people of color and disparities in access to affordable housing, Walton said, “there are going to have to be some law changes that allow us to spell out and call out race, that allow us to call out ethnicity, and allow us to carve out for populations that have suffered the most injustice here.”

Regional and national context

Domestic reparations are not a new idea: The first recorded reparations in the United States were paid in 1783 to a woman named Belinda Sutton, who was formerly enslaved. In the past decade, the concept of reparations has garnered more mainstream attention, most recently bolstered in the wake of the pandemic and the murder of George Floyd by police.

For a recent pilot reparations program in Evanston, Ill., the city gave 16 residents $25,000 each for home repairs and other property costs. The program is part of a broader resolution to give $10 million in reparations to Black people.

California approved the creation of a statewide Reparations Task Force in September 2020 and is considering cash payments among other policies. Meanwhile, representatives have introduced legislation to probe similar questions at the national level without success.

“We’re in a kind of sweet spot, and it’s in a moment of truth and reconciliation,” Chicuata said of the current mood regarding reparations.

The San Francisco African American Reparations Advisory Committee, which meets monthly, formed in December 2020 under legislation introduced earlier in the year by Supervisor Walton. The committee’s 15 members come with a broad range of experiences. If you live in public housing, you can apply to fill a vacant seat with instructions here. The group plans to submit its final reparations plan to the Board of Supervisors in June.

To tune into the March 14 Board of Supervisors meeting, click here. You can dial (415) 655-0001 and enter the meeting ID 2487 791 7160 ## to comment remotely. You may also attend in person at the Board of Supervisors Legislative Chamber in City Hall, which is Room 250 at San Francisco City Hall, 1 Dr. Carlton B. Goodlett Place.

CORRECTION 04/24/23: An earlier version of this story included photos of two buildings, one incorrectly identified as having been torn down. The incorrectly identified structure still stands, and the building in the second photo replaced a different historic building that was torn down on a neighboring block.