Majeid Crawford’s great uncle “Cowboy” was a jazz musician who played on Fillmore Street during its heyday in the 1940s and ’50s, prompting Crawford’s father, Leslie, a saxophone player, to follow in his uncle’s footsteps. But when Leslie Crawford returned to the Fillmore after serving in the army, the “Harlem of the West” and its many jazz clubs had been razed under urban renewal, a controversial initiative to reshape core neighborhoods that San Francisco’s Planning Department later acknowledged was part of a plan to reduce the city’s Black population. The program resulted in the dismantling of many thriving Black districts.

Urban renewal was a publicly and privately funded effort across the U.S. wherein local governments acquired land in areas deemed “blighted” — often using a racially biased lens — through eminent domain, forcibly displacing residents and demolishing existing buildings with promises to rebuild. In San Francisco, urban renewal targeted Black cultural centers and neighborhoods, uprooting thousands of families and destroying lively, well-established communities.

Seeking the “relative acceptance” of Black musicians in France, Leslie Crawford left San Francisco to pursue his musical career in Europe. The move did not go well.

“My dad died of an overdose in France and never returned home alive,” Majeid Crawford wrote in an email. “I blame urban renewal in part for my dad’s death and many others who died from broken spirits and hearts.”

Crawford’s story is one of thousands illustrating the far-reaching effects of urban renewal on San Francisco’s Black communities. Today, he is executive director of the New Community Leadership Foundation, a nonprofit partnering with the city of San Francisco to find people displaced by urban renewal — and their descendants — who might qualify for residences here through the Certificate of Preference Program. Certificate holders move to the head of the line to get into city-funded housing.

Though the program has existed for decades, the city is giving it renewed attention as the Board of Supervisors prepares to review a draft Reparations Plan to address historic harms against Black San Franciscans at a meeting March 14.

Because of high demand, San Francisco runs a lottery for city-funded affordable rental housing and units available for purchase. When individuals apply for units in a particular building, those with certificates of preference are placed in a separate category giving them priority over all other applicants. Then, their applications are reviewed for eligibility. If an applicant is eligible for an available unit, it will be offered to them. The process starts from scratch in each new housing project that is built.

Recent California legislation requires that San Francisco’s certificates of preference — and similar programs in other municipalities — be extended to descendants of people displaced due to urban renewal.

“If you get it, it’s the golden ticket,” said Cathy Davis, executive director of Bayview Senior Services, a nonprofit that provides housing and other services to seniors. The agency asks everyone who walks through its doors, mostly African Americans over the age of 50, for a childhood home address to see if they may be eligible for a certificate.

The Certificate of Preference Program is not new; the first certificates were issued in the 1960s as homes were razed and families were displaced from neighborhoods like the Western Addition and SoMa, though many of those certificates were never honored. The New Community Leadership Foundation hopes to change that and reach newly qualified descendants.

Historical wrongs

A federally and city-funded program, urban renewal led to the displacement of as many as 20,000 San Francisco residents — most were Black, though some were Japanese and Filipino. Writer James Baldwin famously stated after visiting San Francisco in 1963 that urban renewal “means Negro removal.”

It was an era of false promises: “Residents and businesses were given worthless promissory notes that they could one day return, but historically certificates of preference have not been tracked and have rarely been honored,” according to a draft reparations plan prepared by San Francisco’s African American Reparations Advisory Committee.

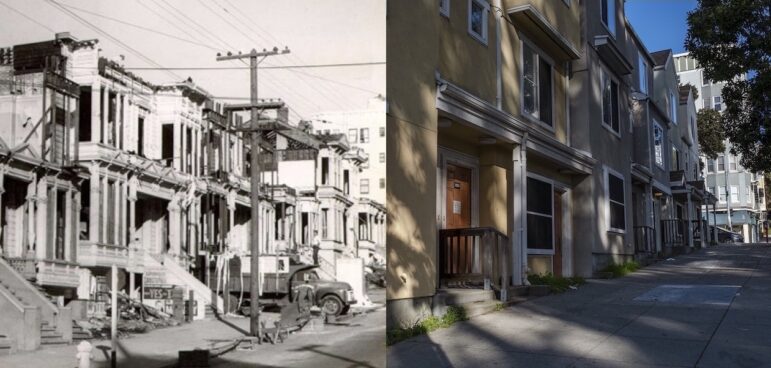

Left: San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Public Library. Right: Yesica Prado / San Francisco Public Press

In 1954, during urban renewal, several buildings on the block bounded by Turk, Eddy, Laguna and Buchanan streets were demolished to build 608 public housing units. Today, the site is known as Plaza East Apartments and remains public housing, though the buildings were torn down in the late ’90s and rebuilt again. In 2021, Plaza East tenants protested that many of the units had once again become dilapidated, which is documented in city records. The developer that owns the buildings is considering tearing them down once more, and rebuilding it as a mixed-income site.At the same time families were being forced from their homes, “a San Francisco Redevelopment Agency survey showed that 34 out of every 35 apartments in the city prohibited African Americans, and the housing that was available was typically segregated, substandard, and expensive,” according to a report from the University of California, Berkeley. Many families moved to new neighborhoods in SoMa, Mission Bay and Hunters Point, and were displaced a second time when parts of those neighborhoods were seized under eminent domain and razed for redevelopment.

Renewed efforts and key changes

In November 2022, the New Community Leadership Foundation partnered with Lynx Insights & Investigations, a private investigation firm, and began scouring records for the names of people who were displaced and their descendants and trying to track them down. They have reached hundreds and anticipate reaching “well over a thousand” in the next two months, Giles Miller, a principal investigator at Lynx, wrote in an email.

Many of the people who were displaced remain in the greater Bay Area, Sacramento and Southern California. People also moved to Texas, the Carolinas and Georgia, Miller wrote.

This renewed tracking effort is benefiting from two key changes: a 2021 law that makes descendants of people who were displaced eligible for certificates, and a stronger commitment by the city to search for and alert people who may qualify.

San Francisco Redevelopment Records, San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Public Library

An aerial view of the Western Addition redevelopment areas in the early 1970s shows the large swaths of land that underwent demolition during urban renewal.The search starts with a document called a “site occupancy record,” which families filled out when they were initially displaced. Investigators cross reference the names on that list (heads of households and dependents) with commercial databases to find potential certificate qualifiers and their descendants, relying on tools like social media when the databases fall short.

Though many initial attempts are unsuccessful, the group is persistent in leaving voicemails and speaking with relatives. Once potential qualifiers are reached, they are referred to the Mayor’s Office of Housing and Community Development, where they are instructed to fill out a certificate request form and may be asked for additional records such as birth certificates.

Since the Certificate of Preference Program was established in 1967, almost 7,000 certificates have been issued by city agencies. In ensuing decades, the program expanded at various stages to include not just displaced heads of households, but other adults who were household members, children who were displaced, and most recently descendants of those who were displaced. But until now, the program has been underused, in earlier decades due to city government not honoring certificates, and more recently due to lack of trust and a lack of information in the communities it is meant to serve.

Of the nearly 7,000 certificates of preference, only 1,483 have been exercised. In January 2022, the Mayor’s Office of Housing and Community Development began issuing the first certificates to descendants of people who lost their homes during urban renewal, and since then has issued more than 30 new certificates to children and grandchildren of displaced residents. As of December, 914 certificate holders were in contact with the office and about 100 were actively applying for housing opportunities.

Reparations connection

Reinvigoration of the Certificate of Preference Program comes at a time when the city has renewed efforts to right past injustices. San Francisco leaders are considering reparations and other potential responses to the historical wrongs of slavery, redlining, urban renewal, displacement and other ongoing disparities. The Board of Supervisors is slated to hold a hearing March 14 on the draft of the city’s Reparations Plan.

In it, certificates of preference serve as one of several mechanisms that could establish whether a person might be eligible for reparations. Suggestions related to certificates of preference include offering certificate holders automatic qualification for city-funded units and first right of refusal for any rental or home ownership opportunities rather than making them enter the citywide affordable housing lottery, giving them stipends to assist with relocation costs for moving into any housing in the city, creating a more transparent process for residents to determine whether they qualify for certificates, and allocating more money for promoting the program and toward displaced resident location efforts.

To Brittni Chicuata, economic rights director at the Human Rights Commission, whose role also includes management of the San Francisco African American Reparations Advisory Committee, certificates of preference are one piece in a puzzle of housing policies outlined in the plan.

“The hope for the housing solutions and recommendations is that there would be kind of a coordinated action or just understanding there’s the ecosystem of housing,” she said, noting such programs as down payment assistance and access to federally subsidized housing. “It takes multiple levers to actually make any progress.”

Employing certificates of preferences in conjunction with the reparations plan “creates a huge opportunity to prioritize this group of people,” she said. “If the city made that political and policy decision to only give housing to people who are on this list until that list was exhausted, that would be reparations.”

Remaining questions

Given the history of racial terror, distrust and shortcomings of San Francisco’s past governmental response to urban renewal, some community leaders still have questions about the scope of the certificate program and the larger affordable housing system within which it exists.

The Rev. Amos Brown said he doesn’t want policy solutions to solely focus on those displaced and their descendants, but to have a broader scope that applies to Black people more generally. Urban renewal “was not done individually, it was done to a group,” he said.

Urban renewal did “indescribably psychological damage to black folks,” said Brown, pastor at the Third Baptist Church in San Francisco and leader of the San Francisco Reparation Task Force’s health subcommittee. Brown is also president of San Francisco’s NAACP chapter and serves as vice chair of California’s Reparations Task Force. In addition to bearing the trauma of these memories, Black San Franciscans today also carry the burden of lower median incomes, more housing instability, and worse health and education outcomes compared with their white counterparts. Black households in the city earn on average $30,000 — less than a quarter of the median white household income.

A lot of people affected by urban renewal who qualify for certificates are struggling to get housing in the lottery system, which Davis of Bayview Senior Services called unfair. Eliminating the lottery for certificate holders, as the reparations plan suggests, could remove this barrier. Davis also said she wants to see the program expanded for those who were displaced in public housing, who do not currently qualify.

Crawford acknowledged that some people who have certificates of preference simply cannot afford available units, even when they are designated “low income,” but said that the program creates an important opportunity for those who were harmed to return to San Francisco, and could act as a galvanizing effort to unite community nonprofits on myriad issues related to affordable housing.

“Billions of dollars of wealth have been stripped from the Black community in San Francisco as a result of urban renewal, redlining and other government policies,” he wrote. “The Black community pulled themselves out of the ravages of Jim Crow just to have everything stripped from them. Reparations is needed to give back what was stolen.”

If you or a family member were displaced during urban renewal and may qualify for a certificate of preference, click here to see a list of affected addresses and here to submit an online application. To find out if you may qualify to be a Certificate of Preference holder, you can visit www.findmysfcp.org, email [email protected], or call 415-275-0035. For more information about the Certificates of Preference program, visit this city website.

UPDATED 3/3/23: Additional details were added to the resource information section at the end of this article.