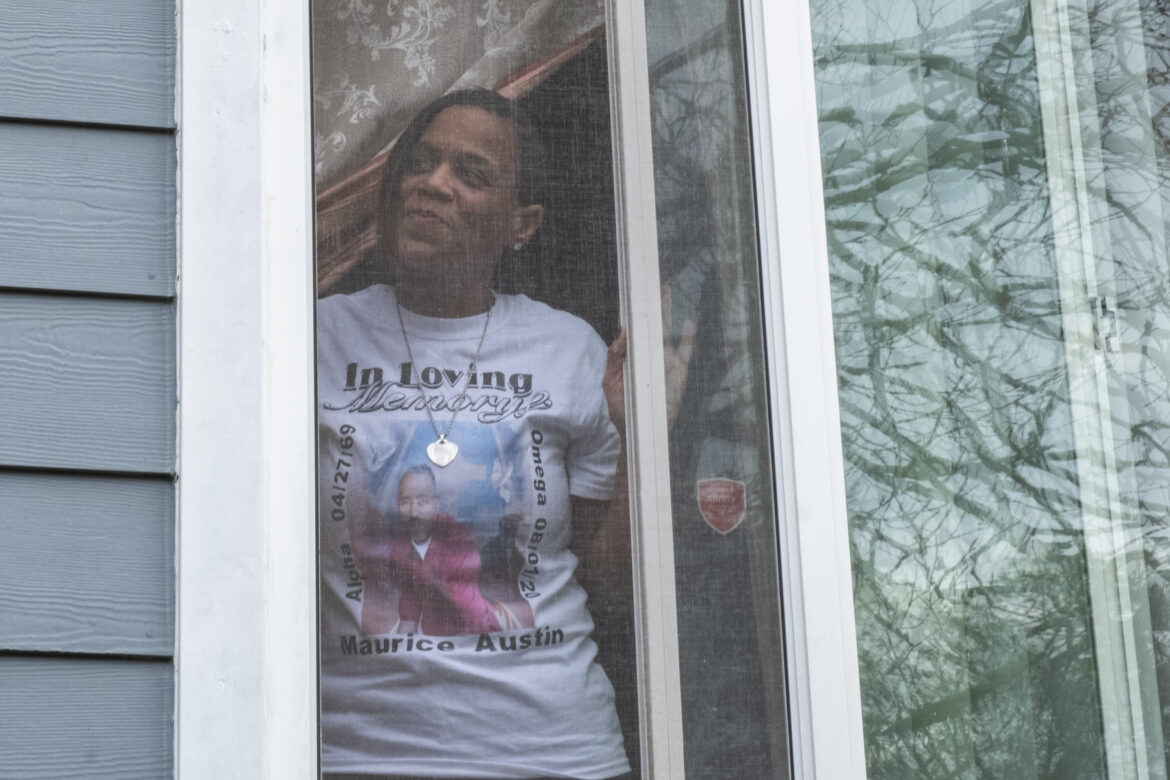

Keeshemah Johnson rushed her partner to the emergency room last summer. Maurice Austin had lost his appetite and wasn’t getting out of bed much. Then he started struggling to breathe. He tested positive for COVID-19 in the ER.

Austin died on Aug. 1, less than a week after Johnson took him to the hospital.

Within days, Johnson said, their landlord began pressuring her to leave. On Sept. 15, she received an eviction notice, stating that she had five days to move out of their Hunters Point apartment. The couple had never added Johnson’s name to the lease — a fact the property owner cited to claim that Johnson and her stepson were illegally squatting in the home they shared with Austin.

“He wasn’t even in the ground yet before they were expecting us to vacate the apartment,” Johnson said.

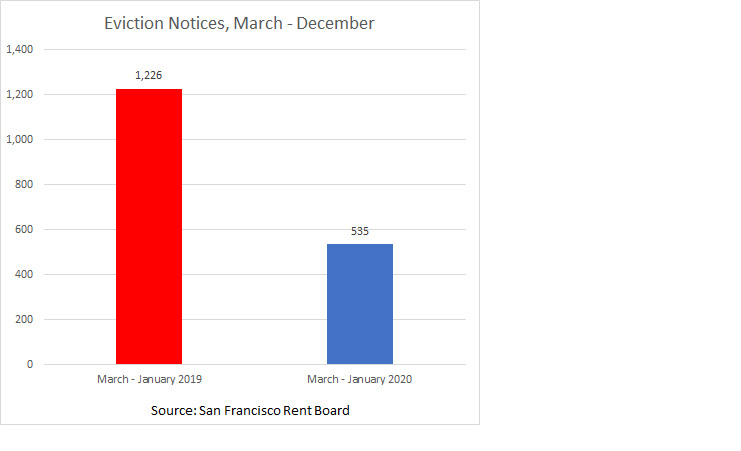

Johnson is among hundreds of San Francisco renters whose landlords have tried to force them from their homes in the midst of a global pandemic. A San Francisco Public Press analysis of the city’s Rent Board data found that from March 1 through Dec. 31, 2019, landlords filed 1,226 eviction notices; during the same period in 2020, landlords filed 535 notices, even as city, state and federal moratoriums on pandemic-related evictions remain in effect.

Frank Bass / San Francisco Public Press

The moratoriums are designed to protect tenants who are unable to pay all or part of their rent due to COVID-19. The measures do not bar all evictions, which, advocates say, puts vulnerable tenants at greater risk of losing their homes.

“The number one reality is evictions are still happening in lockdown,” said Shanti Singh, the communications and legislative director of Tenants Together, an advocacy organization. “Harassment is increasing and people are still getting kicked out of their homes.”

Nuisances and breaches

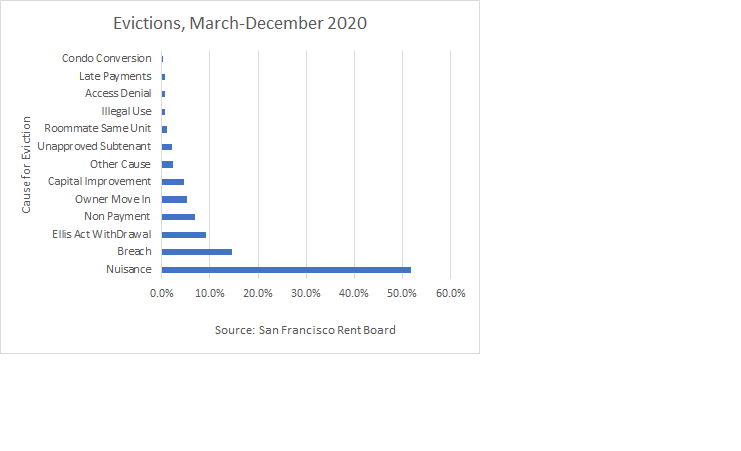

Data from the Rent Board, which oversees the city’s private rental market, indicate that many landlords are relying on reasons other than nonpayment of rent — generally a leading cause of evictions but one that’s been sharply restricted by city, state and federal moratoriums — to try to remove tenants while the moratoriums are in effect.

For the last 10 months of 2019, only one-quarter of eviction notices cited “nuisance violations,” or health and safety issues. While the number of nuisance filings was little changed during the same period in 2020, they accounted for half of all notices as filings in other categories declined.

Other causes cited in the 2020 notices include breach of rental agreements (15%); the Ellis Act, a state law that allows landlords to evict tenants if they take their property off the rental market (9%); and nonpayment of rent (7%).

Frank Bass / San Francisco Public Press

Despite the hundreds of eviction notices filed during the pandemic, the San Francisco Apartment Association, which represents landlords, said its members are focused on the loss of income from tenants who have left the city since March.

“I don’t think that there’s anybody that’s trying to do evictions in a market like we’re in now,” said Janan New, the association’s executive director. “We’re running a 25% vacancy rate.”

Tenants filed fewer wrongful eviction complaints with the Rent Board during the first 10 months of the pandemic, an indication that measures to protect renters are having some impact. Tenants filed 68 such complaints between March 1 and Dec. 31, 2020, compared with 186 in the same time period in 2019.

Advocates say the data do not fully capture the many tactics landlords use to pressure tenants to leave, including harassment and lockouts.

“There doesn’t seem to be any kind of coherent collection or assessment of what’s going on right now,” said Singh of Tenants Together. “So how are you supposed to communicate the urgency of the crisis?”

Poorest districts hard hit

More than 1 in 4 eviction notices with an identified neighborhood were sent to tenants in the Mission and Tenderloin districts, according to the Public Press analysis. The two neighborhoods are home to many of the city’s low-income renters.

A large proportion of notices also went to neighborhoods with more Black residents, including the Bayview-Hunters Point and the South of Market districts.

Yesica Prado / San Francisco Public Press

Keeshemah Johnson’s name was not on the rental agreement at the home she shared with Maurice Austin. She was able to fight off the eviction attempt after he died.Evictions are “going to be in a lot of the neighborhoods with a higher proportion of households of color, particularly Black households, and particularly low-income households,” said Tim Thomas, a researcher with the Urban Displacement Project, a UC Berkeley research initiative that tracks gentrification. “That’s kind of the trifecta of where evictions tend to occur most.”

In 2018, San Francisco voters passed Proposition F to provide free legal assistance to tenants facing eviction. According to data from the Mayor’s Office of Housing and Community Development, legal aid organizations that received funding through the measure provided counsel to at least 328 tenants between March and December of 2020.

The vast majority of tenants who sought that assistance are extremely low-income, and a third are Latino. Seventy requests for aid came from Mission District renters — nearly twice as many as from any other neighborhood.

“The population that can least handle having to deal with displacement during this pandemic are the ones that are being most subjected to that risk,” said Ora Prochovnick, the director of litigation and policy at the Eviction Defense Collaborative, which receives Proposition F funding. “People who are very low income who are evicted often are evicted to the streets.”

“None of us were prepared”

Johnson and Austin were high school sweethearts who reconnected later in life. They had maintained a long-distance relationship for years. She moved from Texas to San Francisco in 2019 to care for Austin, who had suffered several strokes. She found a job as a preschool teacher, while he collected disability.

Yesica Prado / San Francisco Public Press

Keeshemah Johnson displays a photo of her partner, Maurice Austin, who died from COVID-19 in August.Once they were living together, Johnson often dropped off rent payments in person. Their landlord, Northridge Cooperative Homes, owns the federally subsidized housing complex. Austin’s mother had lived in the house before he did. The couple had planned to add Johnson’s name to the lease when Austin contracted COVID-19.

“It all happened so suddenly. None of us were prepared,” Johnson said.

When Northridge Cooperative Homes filed a legal action against Johnson, giving her five days to vacate the apartment, she sought legal assistance. The company claimed Johnson was a squatter, according to court documents the San Francisco Public Press reviewed.

“A lot of tenants, when they get that notice, they don’t realize that they have the right to go through the whole court procedure and have a jury trial before they have to move out,” said Dyne Biancardi, an attorney with Open Door Legal who represents Johnson.

In October, Johnson’s eviction fight went to court. Biancardi argued the filings from Northridge Cooperative Homes included errors that undermined the validity of the complaint. In January, a housing court judge dismissed the case.

In a written statement to the Public Press, the property owner’s attorney, Vernon Goins, said, “In light of the circumstances and impact caused by COVID-19, Northridge elected to pause on recovering possession of the Unit by deciding to take no more legal action.”

For now, Johnson can remain in her home and grieve, surrounded by her memories and photographs of Austin.

“I can breathe,” Johnson said. “I can be grateful that I am still here and that we are able to heal in a healthy way.”

Frank Bass contributed reporting.