Even though federally regulated consumer reports were already exempted from California’s ambitious new privacy law, the companies that sell them spent much of the last year engaged in an as yet unsuccessful lobbying effort to prevent individuals from opting out of sharing their own data from the firms’ databases.

That’s in part because they have diversified beyond consumer reports and credit scores and into the creation of personal profiles based on online information that is less well regulated and critics of the industry call intrusive.

Records of lobbying by the industry show these kinds of requests continued throughout 2019, up to the eve of the law’s implementation on Jan. 1 this year. While the companies failed last year to pass legislation that would pare back consumers’ rights to their data failed in 2019, they have argued that they can refuse to disclose information about consumers in part to protect “the security of the business’s systems or networks.”

Records of lobbying by the industry show these kinds of requests continued throughout 2019, up to the eve of the law’s implementation on Jan. 1 this year. While the companies failed last year to pass legislation that would pare back consumers’ rights to their data failed in 2019, they have argued that they can refuse to disclose information about consumers in part to protect “the security of the business’s systems or networks.”

The arguments they made, in correspondence among the thousands of pages of response to the law, also exposed a little-known aspect of the business: Consumer reporting agencies are transforming themselves into large-scale vendors of unregulated categories of personal information. Those activities now dwarf what was for decades their core business model. They have argued that allowing users to control this data could threaten their ability to provide those services to protect against hackers and thieves.

Much of the lobbying was focused on the category of “fraud prevention services,” a category whose definition is highly contested. Debates in 2020 about amendments to the law are likely to grapple with this question as well.

Emory Roane, policy counsel for the San Diego-based Privacy Rights Clearinghouse, said the term fraud prevention sets “an overbroad and unclear standard that gives businesses far too much leeway to refuse to comply with consumer requests.”

The landmark 2018 legislation, the California Consumer Privacy Act, promises to give consumers greater control over their personal information in a variety of ways. It will let people find out what information companies with large databases possess about them, and compel them to delete or stop selling their most intimate details. It sets penalties for noncompliance — though the office of California Attorney General Xavier Becerra has said it might not have the staffing to pursue more than a small handful of prosecutions against companies each year.

Last February, Eric Ellman, an executive with the Consumer Data Industry Association in Washington, D.C., flew to Sacramento for a hearing hosted by the attorney general’s office. Ellman proposed that business practices including fraud prevention be clearly exempted from the act, which comes into full force in phases throughout 2020.

The law already appeared to protect all companies from consumer requests to delete data if they claimed a fraud-prevention exemption. But consumer reporting firms argued that consumers also should be deprived of the right to opt out of having their data shared with third parties. Why? Because allowing opt-outs would create security holes in their databases that would erode everyone’s security.

“This would affect not only the consumer who requested opt-out, but all consumers, as effective fraud detection requires a large volume of data,” said the submission from Ellman’s association to the attorney general.

Jason Engel, an executive with Experian North America, one of the three largest consumer reporting agencies, expressed a concern similar to Ellman’s in a Dec. 6 letter to Becerra’s office commenting on draft regulations. Engel wanted the state to clarify the “scope” of fraud data that would be spared from deletion.

But Ellman and Engel’s work had consequences for more than the industry’s ability to guard against fraud. Publicly available corporate filings show consumer reporting agencies have developed enormous revenue streams that do not come from federally regulated consumer reports, yet use similar types of data.

Like Experian, two other consumer reporting giants, TransUnion and Equifax, are becoming large-scale data brokers, a term describing technology-based companies that use warehouses full of proprietary and publicly available digital records to create profiles of hundreds of millions of people. These profiles are sold to just about anyone for the purposes of targeted advertising, marketing, fundraising or tracking down individuals — raising just the kinds of privacy concerns that the California law is intended to regulate.

This is a far cry from the activities commonly associated with these companies, and which extensive federal regulations have applied for decades: determining credit, housing, employment or other risk factors on hundreds of millions of consumers and selling them in standardized reports.

Mission creep

Consumer reporting agencies are nowadays engaged in open trade in a broad array of data collection and resale beyond those reports, now representing as much as 80% of the industry’s overall revenues of more than $10 billion, said Pam Dixon, executive director of the World Privacy Forum, a privacy watchdog group.

While each company is slightly different, Dixon said, they “are typically now hybrid entities that have separate business units” performing services “which can be in many cases more profitable than the consumer reporting agency side of the business.”

Experian’s main market is the United States, and the company has a large presence in California, with its North American regional headquarters in the Orange County city of Costa Mesa. The company’s global CEO, Brian Cassin, said in an earnings call with investors last May that the company was seeing near-record earnings through its expanded business practices utilizing personal data.

“It’s been a very good year for Experian, one of our best in history in fact,” Cassin said. He added that he saw identity verification as “a large and growing market opportunity,” since more businesses across the economy are moving online, increasing their vulnerability to sophisticated fraud techniques.

Consumer reporting agencies have been working for years to diversify the consumer data they sell, said Chi Chi Wu, an attorney for the Washington, D.C.-based National Consumer Law Center and an expert on the federal law that regulates consumer reports.

“The mission creep incentive is to sell more data,” Wu testified at a House Financial Services committee hearing last February.

Ed Mierzwinski, senior director of the federal consumer program at the Washington, D.C.-based U.S. Public Interest Research Group, argued that these companies were improperly trying to attribute their broader data-collection practices to consumer reporting or fraud prevention — anything that’s already exempt from disclosure.

“There are several sets of companies and interest groups that are trying to drive a hole in the privacy protections of the CCPA,” he said, referring to the California privacy law, “and the credit bureaus are the most disingenuous, probably.”

Lee Tien, a senior staff attorney specializing in privacy at San Francisco-based Electronic Frontier Foundation, said that “fraud prevention” might be a catch-all, justifying the collection of more than what’s necessary.

“The word fraud is so broad,” Tien said. “It’s very hard to pin down and yet it’s hard to oppose.”

But Lydia F. de la Torre, adjunct professor of privacy law at Santa Clara University, was more cautious. She said that at least part of the companies’ central activities is legitimately intended to protect the public rather than invade their privacy for profit. “A lot of cybersecurity relies on accessibility to threat intelligence,” she said.

For sale: everything about you

One of Experian’s leading products sold to businesses is a tool named CrossCore. The company calls it its “first open fraud and identity” platform, and it is marketed as a comprehensive package to financial firms and other businesses. CrossCore, according to its website, is supported by nearly 300 experts globally. Experian doubled its users in the last fiscal year and has 133 companies using the platform, it said in its most recent annual financial statement.

Experian is also pushing two other services: PowerCurve and Ascend. PowerCurve reportedly makes predictions on how consumers may react to products, while Ascend makes inferences on consumer behavior with machine learning and artificial intelligence. Experian said PowerCurve alone saw a 60% growth compared with the year before.

Neither Ellman nor representatives for Experian returned any of more than a dozen phone and email requests for an interview. Experian spokesman Jordan Takeyama said in an email that beyond comments shared by Ellman, the industry representative, “we do not have anything to add at this time.”

TransUnion and Equifax also did not respond to requests for clarification on their business services, products or public financial statements.

Experian collects and sells a wide range of consumer data to client marketers, who can use it to craft “campaign messaging that truly resonates with each” of their target groups or customers.

One Experian brochure for marketers touts its data on more than 300 million individuals and 126 million households and businesses, enabling clients to “reach niche markets from children to grandparents, mobile homes to mansions.”

According to Experian’s web site, the company sells basic snapshots of consumers that include estimated mortgage amounts and household spending budget estimates. A snapshot with information on 1,000 consumers costs $137.

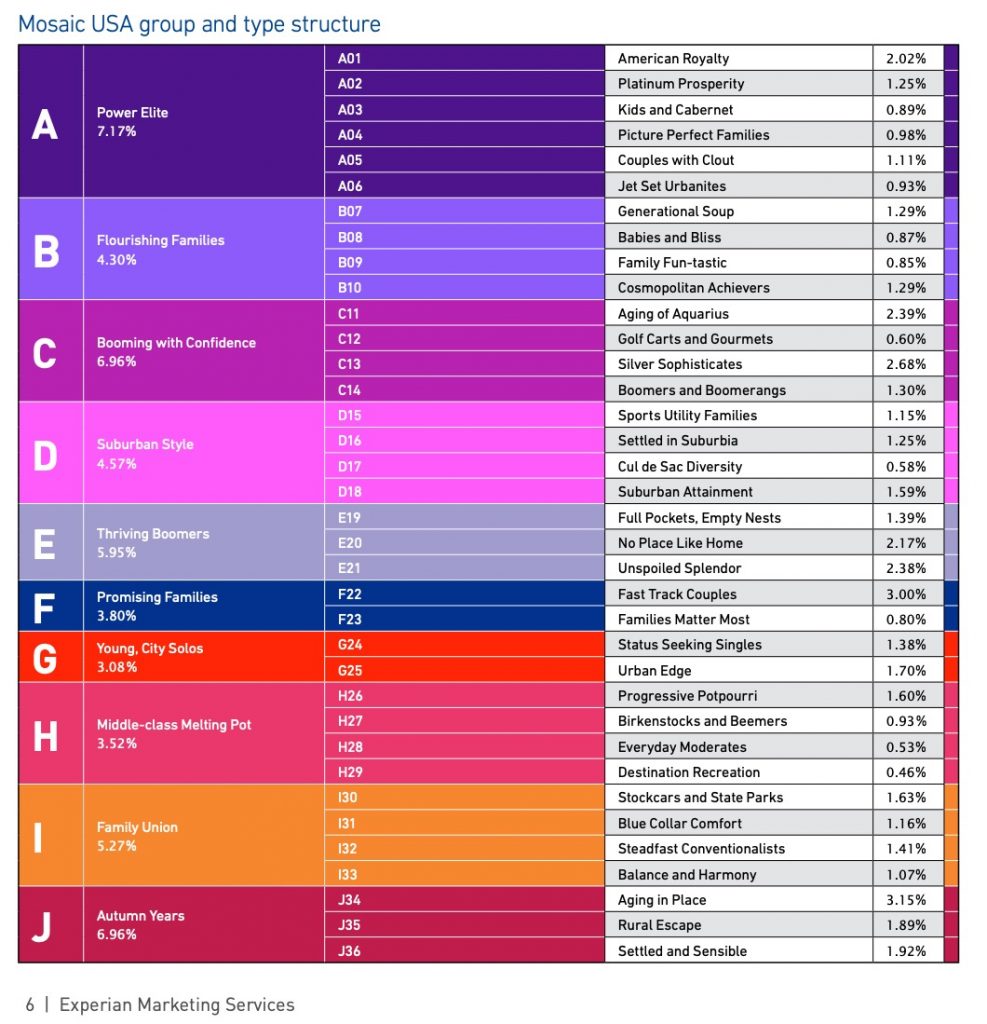

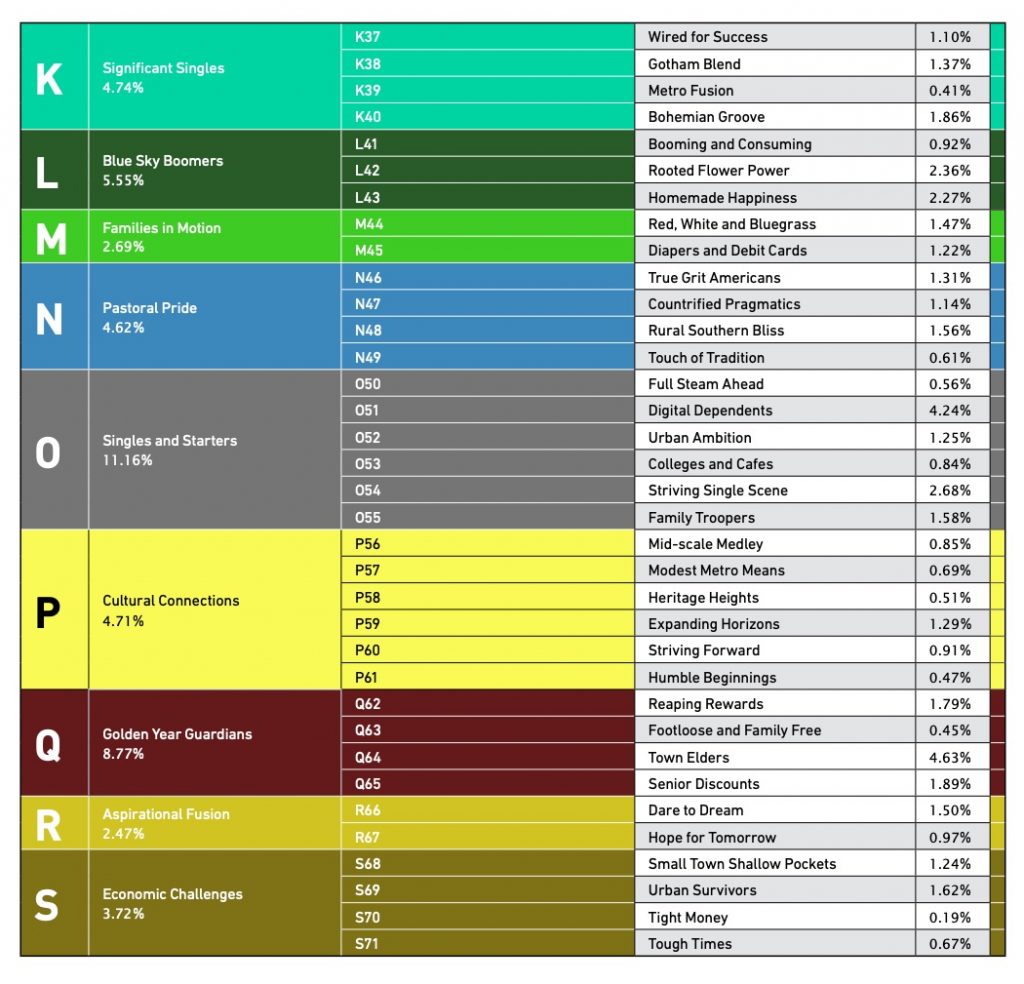

Another of its catalogs sorts American households into 71 categories falling into 19 broad groups. It contains data on consumer marital status, income range, age range and presence of a child in the household. It also claims to reveal a consumer’s ethnic group, status as a homeowner or renter, employment status, level of education and current and past addresses.

The catalog is chock full of colorful labels representing distinct target markets: “Flourishing Families,” “Booming with Confidence,” “Singles and Starters,” “Babies and Bliss,” “Golf Carts and Gourmets,” “Colleges and Cafes,” “Small Town Shallow Pockets” and the dourly euphemistic “Economic Challenges.”

The company also sells the names of expectant parents and families with babies under 3 years old, under a product called Newborn Network in collaboration with Princeton-based marketing data firm ALC. Pricing for the list was not posted on Experian’s website, but for comparison, another marketing list service sold a “pregnant women email/postal/phone mailing list” for $185 for every 1,000 names, with extra charges to filter by income, child’s age and other factors.

Experian even tracks a bevy of seemingly mundane details about consumer habits and inclinations, according to a company document found online: type of motor vehicle owned, hobbies, frequency and destination of travel, preference for movies and TV shows, cellphone usage, number of children and their approximate ages, preference for exercise, dieting patterns, food choices such as vegetarianism, loyalty to brands, preference for frozen and fast food, organic products, political affiliation, position on abortion rights and proclivity to compost food waste.

How they profile consumers

Another Experian catalog for marketers claims that the company’s algorithms can infer whether a consumer has clinical depression or suffers from heart disease, takes a certain brand-name drug or has a dog or cat. It also offers lists based on inferences about whether a consumer has dry or oily skin, or wears contact lenses or glasses.

How do Experian and other data brokers know so much about us? Consumer reporting agencies ingest personal data from social media platforms, said Brett Horn, a senior equity analyst for investment advisory firm Morningstar. They can derive gender and ethnicity from information found on users’ Facebook accounts, including pictures, he said. If such information is used as a metric to extend credit “it could be a minefield,” he said, but the same information used for marketing purposes instead was “not such a problem.”

Experian

What they know will surprise you: Experian promotes its ability to sell marketers targeted information about consumers based on a broad swath of demographic information, including taste in food and drink, investment behaviors, buying habits and the presence of children in the home.Social media is just one type of information source that data brokers use to build consumer profiles, said Robert Gellman, a Washington, D.C.-based privacy and information policy consultant. Much of that information comes from consumers themselves.

Customers might fill out surveys in exchange for coupons and other free information they find useful. If a consumer visits WebMD to research a medical condition, Gellman said, data brokers “can track your purchases, they can track your web activities.”

“You will find that you can buy a list of people by disease,” he added. “You can get a list of people who aren’t diabetics. You can get a list of people by virtually every disease you’ve ever heard of.”

In 2012, the New York Times reported how retailer Target concluded that a teenager was pregnant based in part on what she was buying. “That kind of inference can be done all the time,” Gellman said.

Industry pressure

The lobbying by the consumer reporting industry seems to have been taken seriously in the state Capitol.

In 2019, Experian spent close to $51,000 on lobbying efforts for over a dozen bills including Assembly bills 1416 and 1355, which were amendments to California’s privacy law.

AB 1416, proposed in February 2019 and sponsored by Sacramento-area Democratic Assemblyman Ken Cooley, would have exempted all data used to create fraud prevention services from public disclosure or deletion. The bill would have allowed “a business do essentially anything in the name of cybersecurity protections,” said Roane from Privacy Rights Clearinghouse.

AB 1355, sponsored by Assemblyman Ed Chau, a Democrat from the Los Angeles area, patched up broad carve-outs by consumer reporting agencies to California’s privacy law, Roane said. Equifax paid a firm called California Advocates almost $88,000 in 2019 to lobby on this bill and others.

Consumer reporting agencies lobbied well into September, negotiating language on AB 1355 “up until the last minute,” Roane said. The consumer reporting agencies argued that they were “already regulated” and therefore should not need more restrictions, he said.

In the end, neither lobbying effort weakened consumers’ rights to control their data. AB 1416 failed to leave a Senate committee for a full vote. AB 1355 was signed by Gov. Gavin Newsom in October, though it merely added language to the new privacy law confirming that consumer reporting agencies had the same restrictions with the new California law as they did under federal law, Roane said.

“The world’s largest companies have actively and explicitly prioritized weakening” the new California privacy law, said Alastair Mactaggart, cofounder and chair of Californians for Consumer Privacy, in a statement he posted to the web in September to encourage improved legislation. In a 53-page white paper he penned in November, he proposed to strengthen the privacy law through a fall 2020 ballot initiative called the California Privacy Rights and Enforcement Act.

The new ballot initiative will allow consumers to stop companies from using sensitive personal information, such as sexual orientation or precise geolocation “unless it’s necessary to deliver a product or service to you,” Mactaggart said in a recent sit-down interview. Consumers will be able to tell companies “look, you actually can’t use that to advertise. You can’t use that for any reason unless it’s actually necessary to deliver a product that I actually have asked for.”

Messy responses to privacy requests

Since the new privacy law took effect in January, this reporter tried to request her data be disclosed, to opt out of sales and to have data deleted from all three major consumer reporting agencies.

The process was difficult, making it unclear how each of the companies interpreted their duty to consumers.

Experian made it the easiest to apply online, but after a month, Experian delivered an ambiguously worded statement: “Experian may have shared” personal information with other entities including law enforcement, “Travel, Leisure & Entertainment companies” and “Other.” The company “may have collected” the data from telecommunication firms, “Consumer Inquiries About Experian Products/Services,” and “Other Product Companies Not Categorized.”

Equifax’s online process did not work, and it took three hours on the phone to apply. (Two and a half hours was consumed waiting for an available Equifax representative on a hotline it established for California consumers needing help with their privacy rights. When asked why it took so much time, representative Gabriel replied, “We’re experiencing high call volume.”)

TransUnion’s application process was the worst. It only allows consumers to choose disclosure, opt-out or deletion one at a time. After a request to opt out of sales early in January a TransUnion representative said in a follow-up call: We have no record of you registering for an opt-out.

This series was made possible through the support of the Fund for Investigative Journalism. See previous coverage about the landmark California Consumer Privacy Act: