Veritas accused of trying to force out rent-controlled residents. Big landlord says charges are false.

When the Great Recession destroyed San Francisco’s 20th-century kings of rent-controlled buildings — the infamous Lembi family — the founder of Veritas Investments Inc. began buying pieces of that broken, over-leveraged empire on his way to becoming what is perhaps the city’s largest residential landlord of the 21st century.

Besides bricks and mortar, Veritas shares something else with the Lembi legacy: a lawsuit accusing the corporation of a litany of offenses intended to push out people paying below-market rents so that new residents will pay substantially more as rent caps are lifted. Veritas — the name is Latin for truth — vigorously denies all claims of malfeasance and in turn accuses lawyers and tenants of pursuing a frivolous suit for a big payout.

Besides bricks and mortar, Veritas shares something else with the Lembi legacy: a lawsuit accusing the corporation of a litany of offenses intended to push out people paying below-market rents so that new residents will pay substantially more as rent caps are lifted. Veritas — the name is Latin for truth — vigorously denies all claims of malfeasance and in turn accuses lawyers and tenants of pursuing a frivolous suit for a big payout.

“Veritas chooses to invest in San Francisco and its aging housing stock,” company spokesman Ron Heckmann said via email. “There are no specific claims, fact based or other, about neglected maintenance or pushing out Residents, just boilerplate allegations.”

The company, founded in 2007, says it owns more than 230 apartment buildings with more than 5,000 units, all subject to rent control because they were built at least 40 years ago, with many around 100 years old. That makes the structures cheaper to buy, while expensive to maintain or rehabilitate. The foundation of the company’s business model is to buy and improve these aging buildings, delivering “superior financial performance” to individual and institutional investors, its website states. Founder and CEO Yat-Pang Au, a Bay Area native who pursued a career in engineering before getting an MBA at Harvard, has said he plans to expand the $3 billion Veritas empire around the region, with Oakland as his next stop.

The lawsuit pits a corporate landlord, answerable to investor-owners, against low- to middle-income tenants fearful of being evicted and fighting to remain in a city that has become unaffordable.

When the Public Press first wrote about the lawsuit last fall after activists confronted Au in a protest, Veritas did not respond to requests for comment. In a series of emails this winter, Heckmann rejected claims that Veritas forced tenants out, and defended the company by saying that it had a low rate of complaints and building-code violations.

Lawsuit Expands

Lawyers filed the original lawsuit in October with 69 plaintiffs. The case is known as Evander, et al. v. Veritas Investments, Inc., et al., named after plaintiff Lance Evander, who lives at 720 Baker St. Media coverage and word of mouth prompted more tenants to contact the lawyers, who then filed an amended complaint two months later with additional plaintiffs. In mid-February, the attorneys indicated that they were preparing to amend the complaint again, with more people joining.

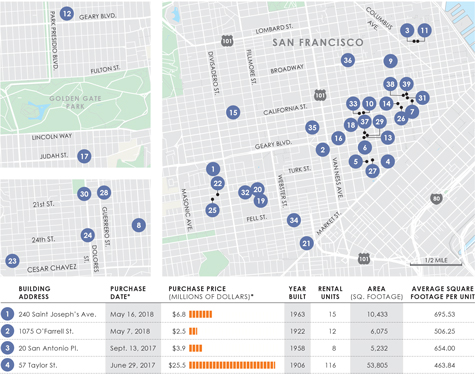

[Click for complete list and additional graphic.]

By late February, there were a total of 106 plaintiffs living in 39 buildings. Among their dozens of allegations, they say Veritas has neglected essential maintenance in occupied units while performing frequent renovations in vacated apartments that are “intended and designed” to inconvenience the residents next door. The plaintiffs also allege that the company passed inflated construction costs on to tenants as rent increases, and sometimes removed asbestos or lead paint “in an unsafe and unauthorized” manner.

Heckmann countered by saying that Veritas “performs repair work and renovations to ensure its buildings adhere to its high standards.” He added that the company paid to rehabilitate apartments and replace furniture in 2018 for several long-term residents “who were not maintaining their units in habitable condition.”

Challenging the claim that construction had made conditions intolerable, he said, “You will note that all but one of the plaintiffs still reside in a Veritas property.”

The suit also charges that Veritas and Au “falsely deny receipt of Plaintiffs’ rents, intentionally make Plaintiffs’ rent ledgers confusing to purposefully allege arrears, and claim fraudulent late charges.”

Heckmann acknowledged that, because the company oversees so many buildings, “it is possible that some sort of billing confusion might arise in an individual case.”

“What we can assure is that both Veritas and the Rent Board provide ample communications to residents concerning the amount of rent due,” he said, referring to the city department that adjudicates disputes in rent-controlled buildings. “More importantly, I wish to make clear that Veritas does not pursue evictions based on some sort of billing mistake; to the contrary, evictions are pursued only as a reluctant necessity due to continued nonpayment of rent or, in rare cases, based on serious tenant misconduct. As I’ve said before, the eviction rate is very low.”

The plaintiffs’ lawyers paint a darker picture.

“You have a very sophisticated business entity that’s attacking the tenants,” said Ryan Vlasak, a partner with Bracamontes & Vlasak, one of two firms representing tenants in the suit. “It’s a pretty unbearable situation that they’re creating.”

Vlasak said Veritas’ offenses differ from those of other landlords in type and scope.

“We’ve never seen all these tactics orchestrated in such a calculated and widespread manner,” he said. “A smaller-scale landlord will pick one strategy and try to stick to it.”

Vlasak, who is working alongside lawyers at Greenstein & McDonald, speculated that this could be “an eight-figure case” — $10 million or more, including punitive damages from Veritas, which has several subsidiaries, including Greentree Property Management. He said a trial could begin within a year and last about three months.

Neither Veritas nor its CEO is listed as the legal owner of any of the 39 buildings named in the lawsuit, according to the real estate database at the Assessor-Recorder’s Office. Instead, the owners are limited-liability companies or limited partnerships, usually named for the addresses. For example, the owner of the apartment building at 57 Taylor St. is 57 Taylor I7, LLC.

Each company is therefore different and seemingly unrelated to the rest. Limited-liability companies or limited partnerships allow owners to reduce legal exposure and reap tax benefits.

“It is a standard, widespread practice in real estate to own properties through specific LLCs, and this practice has been in place for quite some time, not exclusive to Veritas,” Heckmann said.

The plaintiffs live in Veritas buildings concentrated in the city’s northeast. Many are in the Tenderloin, Chinatown, the Mission District and around Alamo Square.

The differences in their housing costs, based on the lengths of their tenancies, are striking. Most moved in over the past 14 years, and eight have lived in their units since the 1970s, court documents show. The tenant with the lowest rent, $247 a month, arrived in 1972. The highest rent is $3,350, shared by two tenants who began occupying their unit in 2017. The highest individual rent is $2,695, for a tenant who started renting in 2015. The lawsuit does not describe the sizes of the plaintiffs’ apartments.

The Lembi Saga

Before Veritas, the Lembi family was the big name in rent-controlled buildings. In its heyday, the company reportedly owned more than 300 San Francisco properties. Rent control limits annual increases in buildings erected before 1979, granting longtime tenants below-market rents.

The Lembis’ story began in the late 1940s, when a young Frank Lembi bought a slew of buildings in probate after returning from World War II. They became the foundation of his companies Skyline Realty and CitiApartments. Skyline and its many subsidiaries, under the leadership of Lembi’s son, Walter, purchased rent-controlled properties and was accused of pressuring longtime tenants into moving out and replacing them with tenants paying higher, market-rate rents.

In 2006, City Attorney Dennis Herrera sued the company for “a shocking panoply of corporate lawlessness, intimidation tactics, and retaliation against residents.” The lawsuit claimed that company personnel used “strong-arm tactics” to pressure tenants to leave, such as shutting off utilities or showing up, armed, at their homes.

The company settled with the city in 2011, admitting no wrongdoing and agreeing to pay up to $10 million.

By then, the Lembi Group was in shambles. It had overleveraged in its efforts to buy up additional properties, so that when the housing bubble burst it was unable to pay back its loans. Big banks, insurance companies and other creditors sued the Lembis and their family trusts, and the majority of their properties were foreclosed upon, seized or sold. Broke, Walter Lembi died of esophageal cancer in August 2010, several months before the settlement with Herrera. The city was able to collect only $836,649 before the defendants went bankrupt, said John Coté, communications director for the City Attorney’s Office.

Veritas CEO Au bought many Lembi properties in the aftermath of the financial collapse, and they accounted for much of Veritas’ holdings at the time, the San Francisco Chronicle reported. In a 2017 profile of Au, he told the San Francisco Business Times that he had maintained a friendship with the elder Lembi — then, 99 — and that they had dinner once a year.

Au’s company faces many accusations reminiscent of those leveled at the Lembis. But while the plaintiffs against Veritas have claimed harassment, the lawsuit does not mention any of the physically threatening tactics that Herrera cited.

The Housing Rights Committee of San Francisco, a nonprofit tenant-advocacy group, has asked the city attorney about taking action against Veritas. In February, Coté said he could not comment “on the existence of any potential investigation.”

Recruiting Plaintiffs?

For Veritas, the motivation behind the lawsuit is suspect.

“The San Francisco Rent Ordinance provides that plaintiffs’ lawyers recover attorney’s fees on such claims, providing a strong incentive to contrive such cases,” Heckmann said.

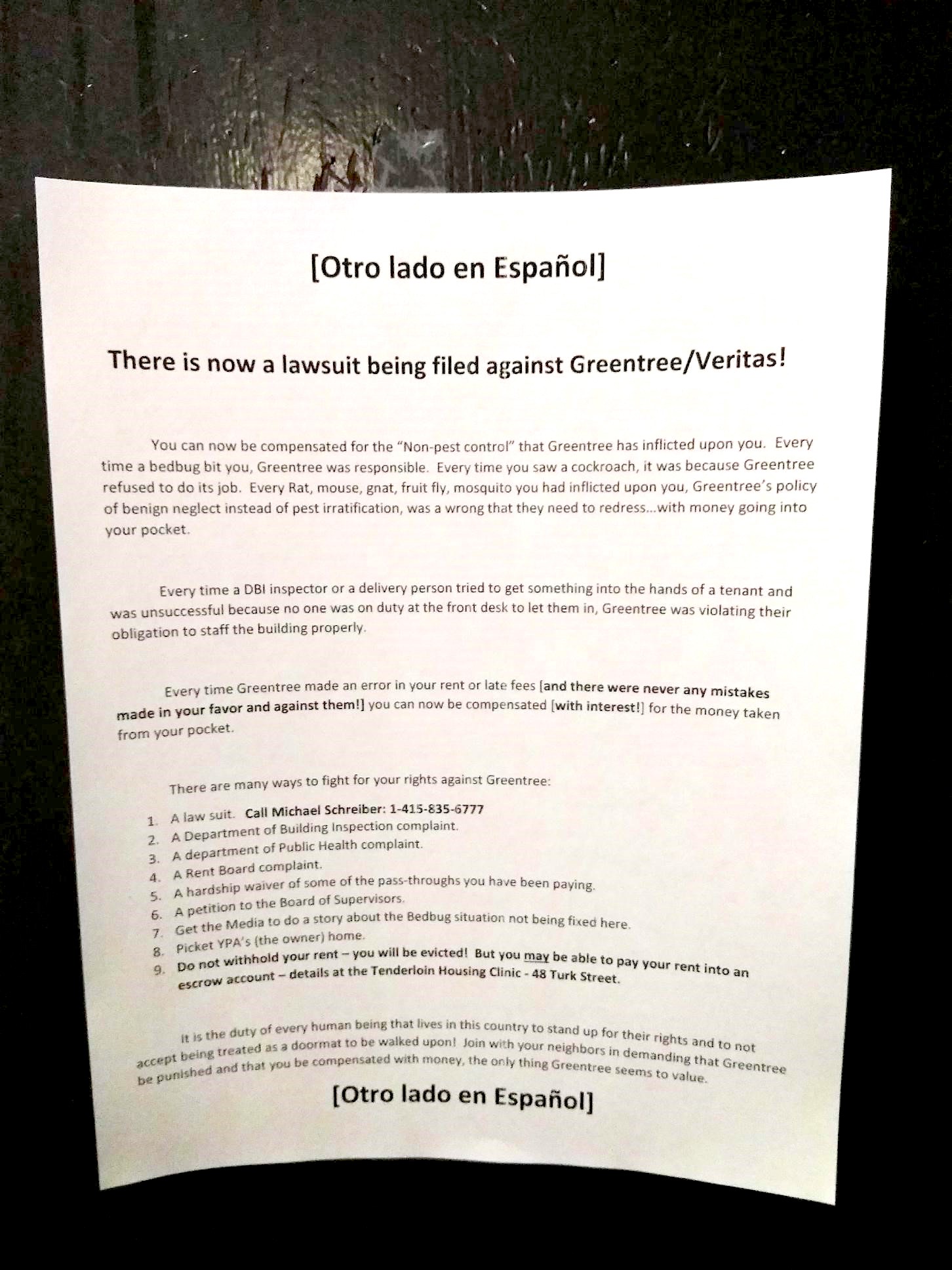

He sent the Public Press a photo of a flier he said was posted at one of the properties named in the lawsuit, though he did not say which one.

The notice said, in part: “There is now a lawsuit being filed against Greentree/Veritas!

“You can now be compensated for the ‘Non-pest control’ that Greentree has inflicted upon you. … Every time Greentree made an error in your rent or late fees [and there were never any mistakes made in your favor and against them!] you can now be compensated [with interest!] for the money taken from your pocket.”

The flier listed nine ways to “fight for your rights,” the first being to call Michael Schreiber, one of the attorneys. Tenants could also complain to various city departments, picket Au’s home or “Get the Media to do a story about the Bedbug situation not being fixed here.”

Vlasak denied that the attorneys had created the fliers.

“Most probably an aggrieved tenant mistreated by Veritas took the initiative,” Vlasak said via email. “Clients come to us for help. Veritas will do all it can to spin its malfeasance as an attorney invention in defense of this colossal lawsuit. There is an organic movement in this City against Veritas’ illegal business practices. We believe Veritas knows this but cares more about money than the residents.”

Rental Data Lacking

In countering the broad assertion that the company is trying to systematically eject long-term tenants and replace them with those who can be charged higher rents, Heckmann said the average tenancy across all Veritas’ apartments is 10 years.

The city does not independently collect records about the length of tenancies in all rent-controlled buildings, so it is practically impossible to assess Veritas’ statements or compare the circumstances of its tenants with those in other buildings. The Rent Board collects this information only in carrying out its complaint-driven petition process, said the board’s executive director, Robert Collins.

“If a landlord didn’t file to increase the rent, or if a tenant didn’t file because they thought they were being evicted illegally, then there would be no interaction between us and that tenant or that landlord during that period of time,” Collins said. Tenants commonly file petitions to have their rents adjusted in response to claims of illegal increases, or reduced services, such as heating, parking or elevator access, he said.

Likewise, the Rent Board can discover that Greentree Property Management is responsible for a building only when either that company or one of its buildings’ tenants files a petition of some kind, forcing identities into the open.

The Rent Board makes individual records available either on computer terminals at its downtown office or through written requests to staff. By comparison, the Department of Building Inspection makes daily updates to an internet-accessible database containing all complaints citywide, making the data set useful for spotting trends.

In recent years, the Department of Building Inspection has received complaints similar to those described in the lawsuit. Several, upon visits by inspectors, were elevated to the official status of code violations.

The lawsuit claims that Veritas has neglected to resolve “habitability defects” like bed bugs and other infestations, water intrusions, mold, exposed wiring, inoperable elevators and accumulations of garbage. The company also exacerbated some of these conditions through “the poor performance of their construction work,” plaintiffs allege.

The lawsuit identifies 14 building code violations in the 39 buildings, adding that the total could be higher.

Heckmann called that “a low rate.” In January, he said that 12 of the 14 had been abated, and that the other two would be resolved as soon as the company obtained a permit and fixed a stuck window — “hardly the stuff of uninhabitability.”

Across its portfolio, “Veritas has an exemplary record of property management and upkeep,” Heckmann said.

Violation Radar, a company that spots complaints and violations only in San Francisco databases, enables landlords to “repair before the inspector arrives,” says a promotional message on its website. Last fall, company spokesman Devon Bradley told the Public Press that Veritas, a client, “has a lower-than-average rate” of complaints and violations than do other landlords.

Heckmann said some buildings Veritas buys “have deferred maintenance issues at acquisition. For such buildings, Greentree works steadily to improve the buildings, sometimes addressing decades of neglect by prior owners.”

Lead-Contaminated Dust

Vlasak said that Veritas and Greentree “are not following proper protocol” for their construction work, and that is especially dangerous when jobs include lead-paint removal. “They’re disturbing it without properly containing it,” he said.

Plaintiff Sofia Uc and her six children, who live at 57 Taylor St. in the Tenderloin, were exposed to lead as a result of construction, Vlasak said. The lawsuit states that her two minor children “both suffered lead poisoning during her tenancy.” Records from the San Francisco Department of Public Health show three cases of lead hazards at the building since 2015. Two occurred in Uc’s studio apartment.

Heckmann questioned Uc’s claim. “Have you reviewed any medical records?” he asked the Public Press. Uc agreed to share her children’s medical records with the Public Press, but had not provided them by the time this article was published.

Uc (pronounced “oose”) migrated to the United States in 2002 from Yucatán state in Mexico, in search of better opportunities. “There’s not a lot of jobs back there,” she said in Spanish, through an interpreter. She works at a restaurant in San Francisco and makes ends meet with the help of food stamps. She and her children moved into the building in 2012, and their monthly rent is about $900, court records show.

The 116-unit building was constructed in 1906, when paint contained lead. It would be seven decades before the federal government banned it in residential properties and public buildings for being a major health hazard, particularly to children.

In 2015, two years before Veritas bought the building, the health department found lead-contaminated dust in her unit. Uc said a visit to the doctor revealed that her son’s blood had elevated levels of lead, known to cause brain damage, likely caused by eating paint chips. The owner abated the paint, and her son’s blood began to normalize.

But a routine medical checkup in November revealed that her infant daughter had elevated lead levels, she said in an interview after joining the lawsuit in December.

In a separate investigation that month, the health department again found paint dust with dangerous lead levels in Uc’s apartment. The dust was “readily accessible to children,” the investigator’s report said.

Uc said Greentree’s recent remodel of her bathroom, kitchen and floor could have loosened the paint.

Heckmann said Uc’s suspicion was unfounded. The work did not include paint removal, “which is typically how such chips could be dislodged,” he said. “Therefore, the assertion does not make sense on its face.”

The investigator ordered Greentree to eliminate the hazards. Heckmann said the company would have done this work anyway, if it had known before Uc reported it to the city. “But that would have meant that plaintiffs’ counsel would not have a story to pitch,” he said, suggesting that the lawyers were playing up the dangers to get media coverage.

“The issuance of an NOV does not mean that the property manager did anything wrong, it just means that there is an issue to fix,” Heckmann said, referring to the notice of violation that the health investigator issued.

The city’s health investigator also found lead in the faucet water at levels below 15 parts per billion, the threshold at which the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency and California Department of Public Health mandate treatment. But the water could “still be hazardous,” the investigator wrote in her report. “The San Francisco Childhood Lead Prevention Program highly recommends that the measures be taken to reduce the lead level.”

The Public Press asked Veritas how it would respond to this recommendation. “As the water testing showed the water to be EPA-compliant, DPH required no further action in regard to water,” Heckmann said, referring to the city’s Department of Public Health.

Greentree temporarily relocated Uc and her family to another apartment while workers addressed the lead-paint hazard. She said she returned to her unit in February when the work was completed.

Uc said that, regardless of the lawsuit’s outcome, she planned to move to another home where her children would be safer. But in San Francisco — where the average monthly rent for a studio apartment was $2,567 in January, according to rental-listing site Zumper — she might end up paying triple for a similar apartment.

Whenever she leaves, it’s almost certain that her old unit will rent for much more than the $900 she paid.

Yesica Prado contributed to this article, which also appears in the spring 2019 print edition of the Public Press.

Do you live in a building owned by Veritas Investments or managed by Greentree Property Management Co.? If so, we’d like to know your experiences. Drop us a line at [email protected].