Oakland will vote in November; S.F. measure being planned for 2019

Is an abundance of vacant units worsening the Bay Area’s housing crisis? That’s what some politicians have suggested. Their solution: a new tax on landlords who leave residential and commercial properties unrented.

Oakland voters will decide in November whether to levy a parcel tax on empty apartments, condominiums and townhouses, plus all vacant industrial and commercial buildings and lots. If two-thirds approve, Oakland would become the first U.S. city to tax so-called ghost homes.

In San Francisco, voters could face a similar measure next year.

In San Francisco, voters could face a similar measure next year.

A vacancy tax was floated in 2015 by then-Supervisor Eric Mar and again in 2017 by Supervisor Aaron Peskin, who, in a research request to the City Attorney’s Office, cited its potential to “help mitigate the impacts of the widespread practice of warehousing valuable residential and commercial units.”

The most often-cited figure for a variety of vacant residential properties is 30,000, which is based on U.S. Census data cited in a 2014 report by the San Francisco Bay Area Planning and Urban Research Association, or SPUR, a local public-policy think tank.

Peskin aide Sunny Angulo confirmed that the supervisor’s office is working to put a vacancy tax initiative before voters in 2019. She said Peskin decided not to push for this November because “there are going to be a lot of taxes on that ballot.” She said it was too soon to provide details about the plan.

Neither city would be the first to address what some critics have called a glut of vacant second homes hurting housing markets in some of the world’s most desirable cities.

Paris began taxing second homes in 2015, and two years later tripled its surtax to 60 percent of the standard property tax. In 2016, Vancouver, Canada, enacted a tax of 1 percent of the assessed value on homes unoccupied for 180 days or more, the first in North America. This year Melbourne, Australia, adopted a tax on properties empty more than six months, and Hong Kong policymakers said they, too, were considering a vacancy tax.

Tom Murphy, a former mayor of Pittsburgh, compared the proposal to an approach his city took for half a century: taxing land at a higher rate — at one point close to six times more — than any improvements on the land. “The theory of it was that if you create a penalty for sitting on vacant land, in effect, by having a higher property tax on the land, then it will encourage people to develop their land,” said Murphy, a senior fellow at the Urban Land Institute. The policy was scrapped in 2001 after an uproar among some homeowners over their land assessments.

“So that’s essentially what San Francisco is talking about,” he added. “For it to work, it needs to be at some level that is painful rather than a nuisance.”

Would It Work — Or be Legal?

Skeptics question whether taxing vacant units would be legal or effective at making more housing available.

“The economic impact is going to depend on how many there are, and what level of tax will get people to change their behaviors, and whether the tax is legal or not,” said David Shulman, a senior economist at UCLA Anderson Forecast. Depending on how the law is drafted, he pointed out, this kind of tax could be viewed as an unconstitutional taking of property.

Charley Goss, government affairs director of the San Francisco Apartment Association, likewise questioned whether a vacancy tax would be legal. He added that small-property owners who leave units vacant often have legitimate reasons, from being burned by bad tenants and having to make large payouts to get them to leave, to keeping units available for family.

“The city passes punitive legislation against property owners all the time, many of whom are low income, many of whom come from other countries, many of whom are monolingual,” he said. The city’s regulations and fees and taxes on property ownership “create an inhospitable environment for them to operate in, which leads some people not to operate in it,” he said, “but then they want to tax you for that, too.”

S.F. Vacancies, With Caveats

So why are politicians pushing this idea? Are thousands of San Francisco residential properties being kept off the market? Without better data, the second question is hard to answer. The first is clearer.

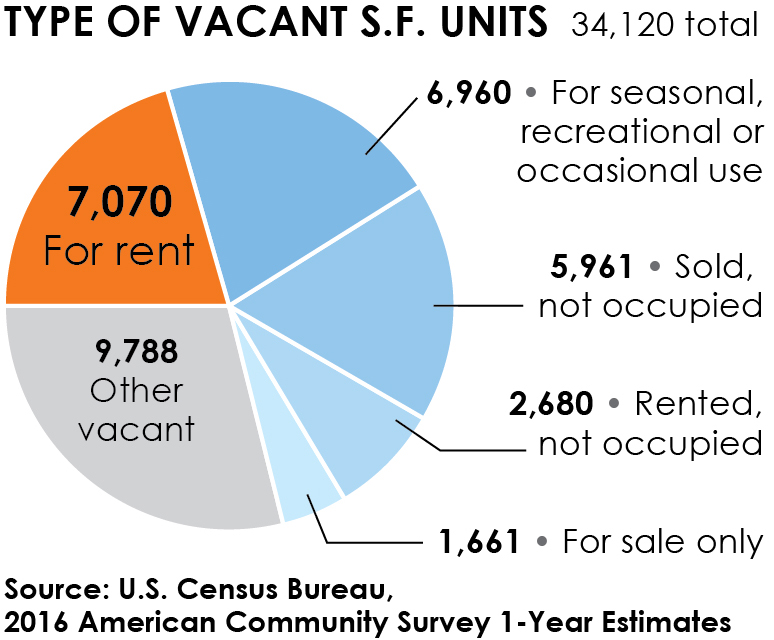

The moves appear to have been prompted in part by the SPUR estimate of 30,000 vacant units,based on 2012 census data. That figure had risen to 34,120 out of almost 387,000 total housing units in 2016, the latest data show.

On its face, that would indicate that vacant units make up almost 9 percent of the housing stock. However, the data come with two big caveats. First, 9,750 units were in transition: either for sale or for rent, or recently rented or sold with a new renter or owner who had not yet moved in. An additional 7,600 homes were either for sale or sold but not yet occupied. That left about 16,700 units kept empty for seasonal or occasional use, a category that could include both second homes and units deliberately kept empty or unoccupied for other reasons. These units make up around 4.3 percent of all the city’s housing units.

Second, the data came from the Census Bureau’s American Community Survey, which samples a relatively small slice of the population and has a high margin of error — around 13 percent for the housing-unit totals and 24 percent for the vacant units. Those numbers indicate that vacant units that weren’t for rent or sale made up between 1.3 percent and 2.3 percent of the city’s homes in 2016.

For context, Reis Inc., a commercial real estate data analyzer, put San Francisco’s apartment vacancy rate at 3.2 percent in 2012 and 4.5 percent in 2017 based on its study of buildings with 40 units or more. Condominiums were not included. Those numbers don’t seem to indicate a glut of vacancies, but without data on condos, it’s hard to say definitively.

Vancouver’s Experience

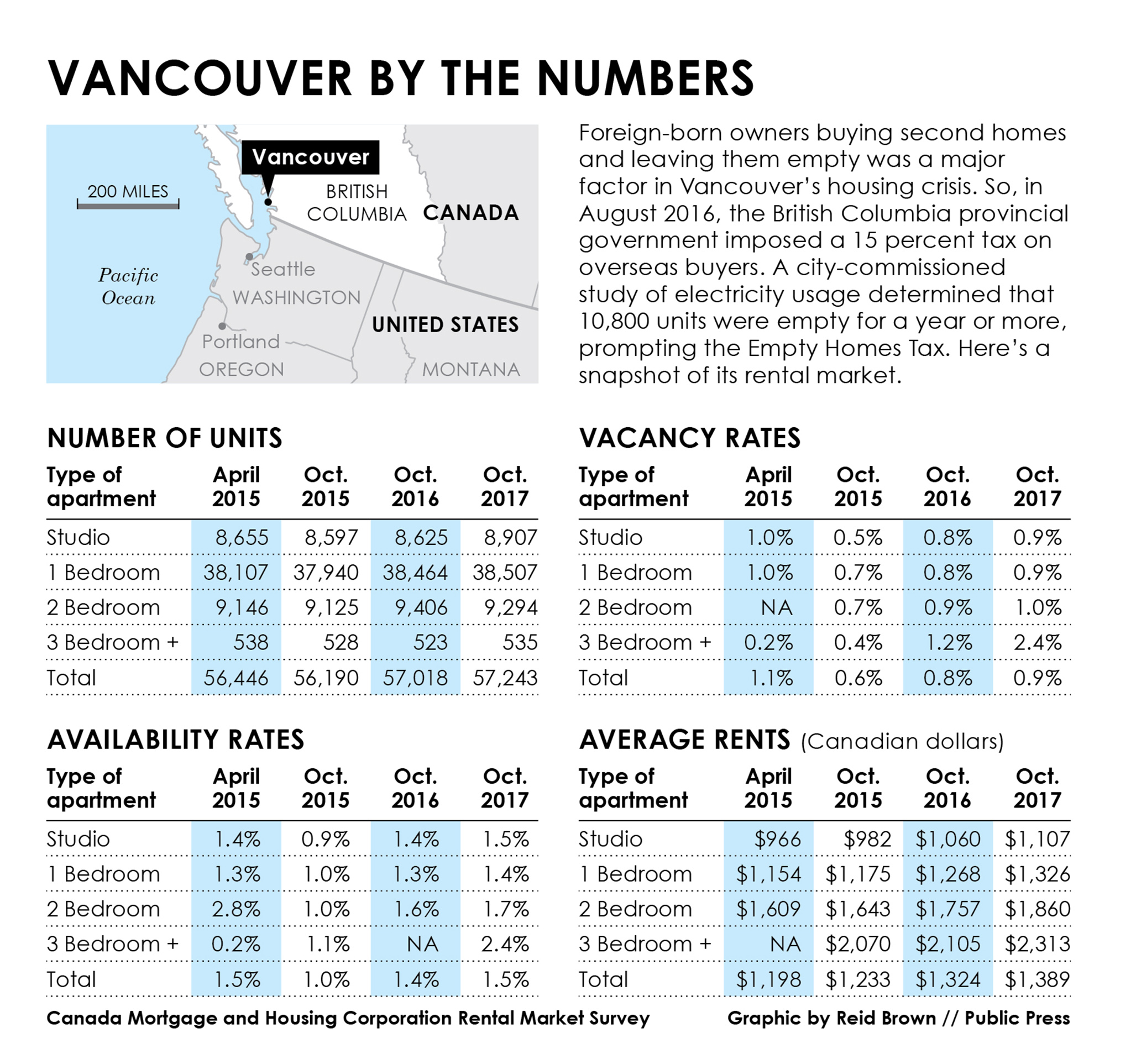

Vancouver faced similar data problems in its effort to tally vacant housing. The city was especially concerned about foreign owners buying second homes and leaving them empty or occupied rarely. In August 2016, the British Columbia provincial government imposed a 15 percent tax on foreign buyers, and weeks later the federal government tightened mortgage-insurance requirements to further discourage ghost homes.

To get a better handle on vacancies, Vancouver commissioned a study of electricity usage that set abnormally low power consumption as a proxy for vacancy. It concluded that 10,800 units were unoccupied for a year or more, resulting in a non-occupancy rate hovering around 5 percent from 2002 to 2014, even as census data showed non-resident occupied units growing by about 50 percent.

“A healthy vacancy rate for a city is considered between 3 percent and 5 percent,” said Patrice Impey, a spokeswoman for the city of Vancouver. “What it means is that if somebody comes to your city to rent something, there’s enough choice for them.”

Between April and October 2015, Vancouver’s already tight vacancy rate grew even tighter, dropping from 1.1 percent to 0.6 percent. So even a slight bump — 0.9 percent last year from 0.8 percent in 2016, according to city data — was cheered as evidence that the market was loosening, thereby increasing available housing.

One factor that helped ease implementation of the tax was that the city didn’t use a time-based system that would have required audits of how often a home was in use, Impey said. Instead, homeowners simply must state whether the property is their principal residence. “That allows us to audit based on straightforward things like your driver’s license and government records,” she said.

Tax Generates $23 Million

Vancouver Mayor Gregor Robertson announced in April that the tax was expected to generate about $30 million (U.S. $23 million) in its first year from 3,300 properties out of about 184,000 total units. Of the 8,500 properties determined to be vacant or under-used, 5,200 were declared exempt from the tax for various reasons, including proof that a unit was being rented out long term, being remodeled or redeveloped, or that the owner works in the city at least six months a year. The highest single tax was $250,000, with a median of $9,900. Proceeds will be directed to housing initiatives.

“We brought in the Empty Homes Tax because we want to ensure that housing is for homes first, not just treated as a commodity,” Robertson said in a news release. “With a near-zero vacancy rate, we can’t have homes sitting empty while people who want to live and work in our city are struggling to find a place to rent.”

For San Francisco, the questions and answers are less clear-cut. Without better data, officials can’t quantify the scope of the problem or estimate how many units a vacancy tax might free up.

And to some observers, the shortage of affordable housing is more of a supply problem than anything else. Since 2010, San Francisco has added more than 78,000 residents, but just over 31,000 housing units.

“The solution is not a vacancy tax,” said Shulman of UCLA. “The solution is changing the zoning and building more housing. Everything else is rearranging the deck chairs on the Titanic.”

This article also appears in the summer 2018 print edition of the Public Press.