A tax or lawsuits would target ‘flippers’ to save tenants and rental housing. A 2014 effort failed.

In their 2018 mayoral campaigns, former state senator Mark Leno and Supervisor Jane Kim emphasized the role of speculators in driving gentrification and displacement in San Francisco.

To curb speculation, which has boosted prices and profits, Kim proposed a stiff tax to make it unprofitable to buy and quickly sell properties for a handsome profit — a practice called flipping, which has displaced renters citywide. Though voters rejected a similar tax in 2014, Kim said the idea “absolutely” still has a future, one that she plans to pursue.

In San Francisco, voters could face a similar measure next year.

In San Francisco, voters could face a similar measure next year.

Leno pledged to take speculators to court — specifically those who repeatedly evict tenants by exploiting weaknesses in the state Ellis Act, which allows landlords to clear their buildings if they want to exit the rental business. He said speculators are robbing the city of desperately needed housing, a trend that is “not sustainable.”

But what constitutes speculation? And would efforts to curb it pass political and legal muster?

At heart, to speculate is to bet that housing prices will rise, based on increasing demand. Speculators profit because they capitalize on an upturn in the market, not because they create value or provide a service. Speculation drives displacement because it usually requires evicting or buying out tenants. It’s an engine of gentrification because it catalyzes turnover from lower-paying renters to higher-paying tenants or buyers. There’s also evidence that speculation overheats demand and raises overall market prices, not just for those buildings bought by speculators.

There’s no single way to distinguish speculation from other real estate transactions. It’s a murky concept. So, researchers and policymakers use various indicators. For example, cash purchases can be an indicator of speculative investment because institutional investors, unlike most individual buyers, have abundant capital to forgo a mortgage. Vacancies and foreign buyers are also possible indicators that units are being used for investment purposes rather than as a primary residence.

In Kim’s version of a speculation tax, speculators are defined as flippers — buyers who resell their properties after a few weeks or months or a year of appreciation, with no intention of becoming long-term landlords. House flipping, by means of the Ellis Act or otherwise, is less prevalent in San Francisco than it was after the Great Recession, when the real estate market and high-paid technology jobs soared in tandem.

In 2014, 54 percent of voters rejected an anti-speculation tax, Proposition G, one of the most furiously debated housing measures the city had seen in years. The real estate industry spent at least $1.4 million opposing the measure, which would have taxed speculators who resold properties quickly.

Ellis Act Abusers

When Leno talked about “taking speculators to court,” he referred specifically to Ellis Act abusers. Flipping property is immediately profitable only if an owner is able to sell a building quickly, replace existing rent-controlled tenants with new tenants paying market rents, or convert to condominiums. So intervening legally on speculators’ ability to evict is another way to curb speculation.

No U.S. city has enacted a speculation tax. The closest to success was Washington, D.C., in 1978, when the district council passed such a levy. But it was quickly rescinded after opposition from real estate groups along with African-Americans, then the majority of residents. One explanation for its defeat is that African-Americans perceived the tax as an attempt to suppress the creation of property wealth by means of rehabilitating or selling properties by and for African-Americans. Such a narrative is unlikely in today’s San Francisco.

Here’s how such a proposal would work: A graduated real estate transfer tax would be paid on multiunit buildings resold within five years of purchase. If a building is resold within one year, the tax would be 24 percent of the resale price; within two years, 22 percent, and at five years, 14 percent. The point is not to generate city revenue, but discourage and eventually stop flipping.

If Proposition G had passed, how many homes would have been protected from speculation? According to Redfin, a national real estate brokerage, 388 multiunit buildings have been resold within five years of purchase since 2012. Redfin estimates that would come out to about 970 units, or 162 every year. But it’s important to note there’s no way to know how many of those would have been exempt under Proposition G, which made allowances for things like emergencies or job transfers that might force a buyer to resell quickly.

“The fact is that the vast majority of evictions are happening by seven to 10 large real estate speculators,” Kim said. But, she explained, the 2014 measure was portrayed by the opposition as burdensome to average San Franciscans.

Jay Cheng, of the San Francisco Association of Realtors, said at the time that attacking speculation “was overtly politically driven policy and was not a solution for the issues we faced.”

“There were a lot of misleading ads,” Kim said. “The opposition spent a lot of money to conflate a speculation tax with a tax on regular homeowners,” such as those who have an in-law unit or a duplex.

The opposition’s messaging prevailed despite the fact that owner-occupied buildings were exempt from the proposal. Kim now supports a version of the tax that applies only to buildings with three or more units.

Flipping Vs. ‘Productive Activity’

So far, however, no one has found a way for the tax to distinguish between flipping — quickly profiting from appreciation — and what’s considered “productive activity.”

“If somebody buys the home and makes a bunch of improvements on it and then sells it, is that speculation or is that a productive business activity that uses available capital to improve the housing stock?” asked Eli Moore, a researcher with the Haas Institute at UC Berkeley. He cautioned that discouraging or penalizing rehabilitation could negatively affect contractors and anyone else in the construction trades.

It might be possible to structure the tax in a way that distinguishes between pure speculation and more productive activity. It could, for example, exempt from taxation the value of improvements made to the building. But, so far, no such proposal exists.

Kim doesn’t see renovation as a reason to go soft on speculators. If capital is needed to maintain San Francisco’s housing stock, “I think that the city can and should provide low-interest rehabilitation loans,” Kim said. “We already do that … and we should greatly expand that program. I think that you can have an anti-speculators tax and still support responsible landlords in maintaining their properties.”

If an anti-speculation tax prevails, it will likely be challenged in court. But San Francisco has “significant leeway in enacting tax legislation that has the effect of discouraging house flipping and the like,” said professor Leo Martinez, at the University of California Hastings College of the Law.

Opponents of Proposition 13, which caps property taxes, unsuccessfully challenged a 1992 California Supreme Court ruling in which the justices declined to judge the wisdom of the system of taxation “absent harshness or oppression.” Martinez said he would “expect a similar challenge in a house-flipping tax,” and, as in the challenge to Proposition 13, “a failure of the argument.”

In 2014, while Kim was pushing the anti-speculation tax, Leno tried and failed to reform the Ellis Act in the state Legislature. During his failed bid for mayor this year, the former supervisor and assemblyman said that, if he were mayor, he would work collaboratively with the City Attorney’s Office to build an unprecedented case to penalize scofflaw speculators.

Taking them to Court

“I would like to send the message to the folks who are doing this, that there’s a new sheriff in town,” Leno said. “They’re not going to be able to get away with this any longer.”

The Ellis Act was written to protect landlords who want to go out of the rental business and must evict their tenants. But speculators exploit the law by purchasing buildings, temporarily “becoming landlords” and then invoking the Ellis Act to “go out of business” and evict everyone so the building can be quickly resold for a sizable profit.

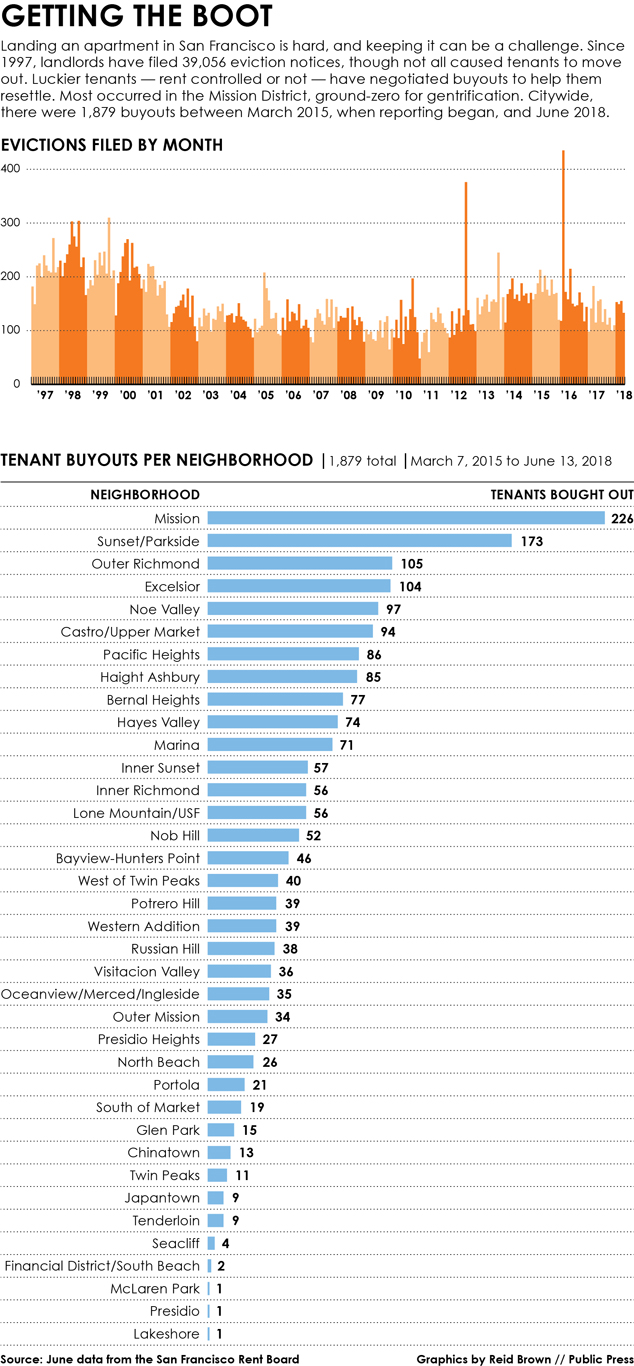

Since 2016, 163 San Francisco households have been evicted through the Ellis Act, according to the Anti-Eviction Mapping Project. The rate has stayed relatively steady after dipping during the recession. That number doesn’t reflect almost 1,879 tenants since 2015 who have accepted buyouts from their landlord rather than be evicted, Rent Board data show. It also doesn’t reflect the thousands more who are priced-out through other perfectly legal means. And yet, in Leno’s view, the city can’t afford to lose any rent-controlled dwellings.

“It’s so expensive for us to build new affordable housing, our first priority has got to be protecting the existing stock,” Leno said. “For every 10 new units we build we’re losing four. That’s not sustainable.”

Leno’s 2014 effort was to amend the state law to prohibit owners from using the Ellis Act to evict tenants for five years after purchasing a building; limit repeated use of the Ellis Act to evict tenants from multiple homes; and to levy fines and penalties for violators.

The San Francisco and national Realtors associations were, again, instrumental in defeating Leno’s reform effort.

“Even if rental property owners are losing money every month, it would force property owners to stay in business against his or her will,” the Realtors wrote about Leno’s legislation. “The bill will only worsen the housing situation in San Francisco, and seriously impact the lives of small property owners and homeowner families.” The San Francisco Realtors group did not respond to numerous requests for comment on this story.

Speculation Influences Market

Speculation doesn’t affect merely the tenants who are displaced or outbid. Because speculators with deep pockets or institutional financing can afford higher prices, they can overheat demand. That means average prices may rise sharply, and because property is overvalued, fall more precipitously at the end of a cycle than in markets with less speculative activity.

Today, flippers are focusing on other areas of California where prices are rising and it’s easier to “buy low, sell high.” But, as always, the market is cyclical. Supporters of a speculation tax argue that it can be thought of as an automatic stabilizer, remaining dormant when speculation is low and activating to deter price increases due to the creation of artificial demand during boom times.

However, it’s hard to predict how much curbing speculation would stabilize overall prices. Institutional investors aren’t the only ones with the means to outbid ordinary buyers.

Over the past 12 years, one-fifth of single-family home and condominium sales in San Francisco were all cash, according to reporting by the statewide public affairs news site CALmatters.

Some analysts say that institutional buyers dominated cash purchases in the years immediately following the recession, but that has changed, and a larger portion of buyers of real estate are super-rich individuals, often living outside the United States. Most of those all-cash properties weren’t flipped, however, so neither they nor the massive inequality driving housing unaffordability would be affected by anti-speculation efforts.

This article also appears in the summer 2018 print edition of the Public Press.