Fates of Hundreds Unknown After Subsidies Expire; Some End Up Homeless Again Amid Strains

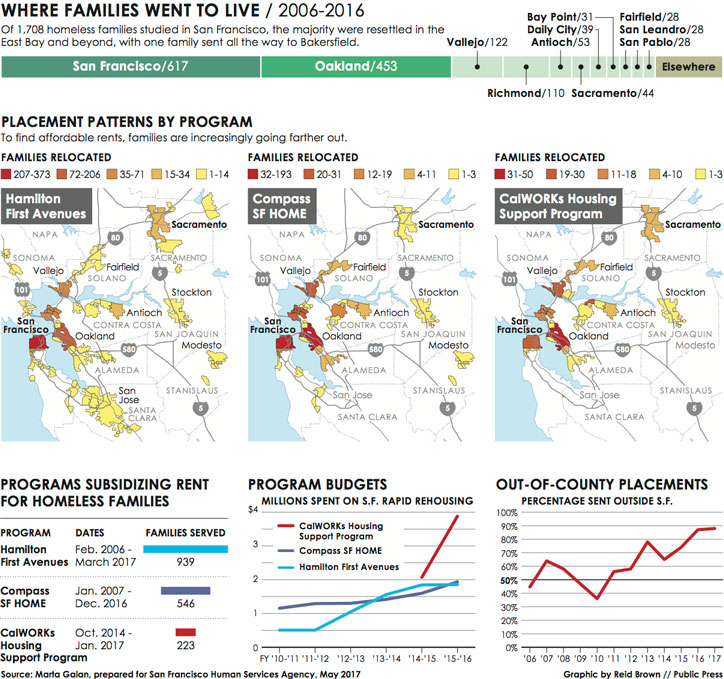

A San Francisco initiative to help homeless families find affordable apartments and assist them in paying the rent is sending most of them out of the city because of the high cost of housing. The families are moving to Oakland, Richmond, Vallejo and, increasingly, to the edges of the Bay Area and beyond, such as Stockton or Sacramento.

The multimillion-dollar subsidy program, called Rapid Rehousing, has helped hundreds of families regain their footing after an eviction, job loss or other crisis left them homeless, and for many families it has worked: They stabilize and remain housed after their rent assistance runs out.

But one year after their subsidies end, some families end up homeless again, and the whereabouts of hundreds of other families are unknown because they lose contact with their service providers. As a result, it is difficult to gauge the long-term success of the program, a Public Press review of data has found.

The number of families leaving the city through the program has been rising steadily over the past decade, from 45 percent in 2006 to 87 percent in 2016, according to an internal report prepared for San Francisco’s Human Services Agency that tracked 1,708 families. For 2017, the agency put the figure at 88 percent.

Family Ties Frayed, Stability Difficult

“This trend raises new questions about the efficacy and costs of the Rapid Rehousing model in San Francisco,” the report’s author wrote, in part because the emergency and family shelters where many families return after their subsidies end are “amongst the most expensive interventions.”

For families, relocating out of the city frays social ties and makes it harder for people to keep jobs, get child care and stay in their new homes, according to the report and officials of nonprofit agencies interviewed by the Public Press. Agency leaders are anguished about the growing exodus of so many families, yet see no other options.

“We’re chasing our families out,” said Lenine Umali, director of external affairs and policy for Compass Family Services, the lead intake agency for homeless families in San Francisco. “We rip them out of their home and send them to other cities where they have no connections and no history and no services.

“We know this is a symptom of displacement and wealth inequality, and those are things we fight against. But you can only do so much.”

Official Calls Research ‘Misleading’

The precise number of families who return to homelessness after their subsidies expire is unclear, partly because the status of so many of the families is unknown. The May 2017 report was prepared by Marta Galan, a University of California, Berkeley, graduate student who interned with the Human Services Agency. She found that one year after rental assistance stopped, the status of more than 60 percent of families was unknown. Galan based her findings on data from Compass and Hamilton Families, the nonprofit agencies that provide subsidies to most of the city’s homeless families.

Jeff Kositsky, director of the city Department of Homelessness and Supportive Housing, Hamilton’s former chief executive and a proponent of data-driven solutions, faulted the methodology of Galan’s report and called it “misleading.” He did, however, acknowledge that she had “uncovered some theories worth testing.” His office forwarded data to the Public Press that claimed a roughly 90 percent success rate for the program, but that ignored the large numbers of families whose status was unknown after their rent subsidies expired.

Trent Rhorer, director of the city Human Services Agency, also had issues with Galan’s report. He said some conclusions about the CalWORKs subsidy program were based on too small a sample but added, “I believe 100 percent that her data is valid and accurate.”

Galan did not respond to several requests to discuss her research.

City Unifying Databases to Improve Services

San Francisco, with one of the highest national rates of homelessness, is in the midst of a major restructuring of its programs, which Kositsky is driving. Under former Mayor Ed Lee, who died in December, the city announced an ambitious plan to end family homelessness by the end of 2021.

The city is rolling out a data-driven “coordinated entry system” that aims to create a unified database of all people assisted by the city’s homeless services system, starting with families. The Online Navigation and Entry System aims to immediately get homeless families into shelter or housing and does away with waiting lists for families defined as high need: those sleeping on the streets or in their cars.

A cornerstone of the city’s plan is the Rapid Rehousing initiative that provides subsidies to move families into rental housing. The concept emerged from local programs in Los Angeles; Hennepin County, Minnesota; and Lancaster, Pennsylvania, and went national with funding from the Obama administration’s 2009 stimulus package. These programs aim to provide rental assistance to people shortly after they become homeless, on the theory that the longer they remain unhoused, the harder it is to keep them from becoming chronically homeless.

In the San Francisco effort, carried out by Compass and Hamilton, housing specialists hunt for vacancies and cultivate relationships with landlords. Families get rent subsidies averaging, in the case of Hamilton, $1,400 a month, as well as help with deposits. But the catch — and one with profound implications for the composition of the city’s population — is that the vast majority of the housing is outside the city.

Relocation Key to Homelessness Effort

Sending people out of San Francisco has become a key part of the city’s effort to address homelessness. The city began offering Rapid Rehousing subsidies in 2006 under former Mayor Gavin Newsom, who in 2005 also initiated the Homeward Bound program that provides homeless people one-way bus tickets to join family members or friends elsewhere. About 850 homeless people leave the city each year through Homeward Bound, which also accounts for the most common exit from the city’s navigation centers, the Public Press reported in summer 2017.

These initiatives leave homelessness advocates fearing that San Francisco’s pledge to end family homelessness by 2021 is predicated primarily on large numbers of low-income families simply leaving the city.

“In our desperation to house homeless families, we are losing the city’s lifeblood — our diversity, our neighbors, our talent, our friends and our family members,” said Jennifer Friedenbach, executive director of the Coalition on Homelessness. “San Francisco must invest fully in housing that keeps impoverished families in our city. We have done some of that, but we need to do a whole lot more.”

Defense of Rapid Rehousing

Kositsky said the city is trying to address the crisis for families in the most humane and rational way possible — by working to get them off the streets and into housing as fast as possible.

“Is it better for a kid to be homeless for two years, struggling and bouncing between shelters, or to get quickly housed somewhere else in the region where real estate prices are more affordable?” he asked in an interview at his Mission Street office.

“One reason we don’t make enough progress addressing homelessness is because people want to engage in magical thinking that we’re going to be able to build enough housing for all the people who are earning below 35 percent of area median income,” Kositsky said. “That’s just an unrealistic expectation.” In 2017, a Bay Area family of three at that income threshold made $31,150, according to data from the mayor’s office.

Under the banner of “housing first,” Kositsky’s department devotes about two-thirds of its $239 million annual budget to rent subsidies, housing counselors and providing 7,403 long-term supportive housing units in the city to people who need services beyond rental assistance — 710 of them earmarked for homeless families. By 2022, the city plans to add 1,367 supportive housing units, including 527 for families.

In 2015, and again in 2017, the city’s biennial Point-in-Time count found about 600 family members to be homeless on a single night, nearly all of them in emergency shelters. But because many families come and go, data from the city’s new online navigation system showed that for a three-month period ending Nov. 21, the city’s homeless services had housed or assisted 3,406 unique family members.

‘Unknowns’ Excluded From Success Claims

Kositsky said that if he can show solid results in reducing the number of homeless people on the street, San Francisco residents and political leaders might be more willing to invest in new affordable, subsidized housing in the city for homeless and low-income families.

Galan’s report looked at a decade’s worth of data for the Hamilton First Avenues program and Compass-SFHOME and found that one year after rent subsidies ended, 28 percent of the families that left San Francisco and 43 percent who stayed here were considered to be stably housed. Between 1 percent and 6 percent of those tracked were known to be unstable while the status of the rest of the families, a majority of the total, was unknown.

Kositsky and his staff offered conflicting figures. An email from spokesman Randolph Quezada put it succinctly: “We find 88% outside of SF and 93% within SF were stably housed. RRH (Rapid Rehousing) programs work.”

But those figures ignore the large number of unknowns. Indeed, these dueling analyses make completely opposite assumptions: Galan’s metric for stably housed families is a percentage of all families in the program, including those whose status is unknown. The city calculates the stably housed as a percentage of only those whose status is known, leaving the unknowns out of the equation even though they represent at least half of the families served.

After the city pushed back against Galan’s findings, the Public Press requested data from both Compass and Hamilton. Both reported not knowing the status of large numbers of families one year after their subsidies ended: Compass couldn’t reach or didn’t know the status of two-thirds of the families and Hamilton had no data on about one-third.

CalWORKs Program Also Examined

Galan also examined a smaller, state-funded rent-subsidy program offered to recipients of CalWORKs, California’s cash assistance program for low-income families. Since its start in 2014, she found, CalWORKs has provided rent subsidies to 223 families. Of 113 tracked, 91 were placed outside San Francisco. Of those, 49 returned to San Francisco after their subsidies expired and 37 became homeless or lived in unstable housing. The other five families were unaccounted for.

Caseworkers from the three rent-subsidy programs interviewed by Galan identified numerous problems facing families that left San Francisco. Many could no longer see their doctors. Some had run-ins with their new landlords, making it hard to get housing references. Others fell off waiting lists for public housing.

She also randomly contacted eight CalWORKs families who moved out of San Francisco to ask about their experiences. Seven of the eight had returned to the city and to “insecure housing situations” after their subsidies ended.

Success Stories From Rent Subsidies

Two of the families told her that despite problems with the program, it made their lives better. “I would not be where I am today if it had not been for this program,” a member of one family told her. Another said the family’s caseworker had been “phenomenal.”

Four of the families felt the program set them back, Galan reported. One complained that it ended abruptly and as a result, “I lost my housing, my job, my child care and my aide all at the same time.” Another said, “The program helped me get on my feet, then pulled the rug from under me. It caused me to go backwards in all of my progress.”

The subsidy program helped Regina Bates, a 50-year-old mother of two who was born in San Francisco and has lived all over the Bay Area. Her experience with homelessness began in 2010, when she lost a job as a medical receptionist after fracturing her foot and going on disability leave for six months. The ripple effects caused her to lose her apartment and put Bates and her family under stress.

“Suddenly I had nowhere to live and no job — homeless with an almost-3-year-old,” she told the Public Press.

For the next few years, she moved around, with one and then two daughters in tow. She stayed with family in Dallas and Atlanta, slept in her car, crashed with friends in Berkeley and stayed several times at the Richmond Rescue Mission, once for four months. In 2013, the family moved to Las Vegas and lived with Bates’ niece.

The next year, the family moved in to the Hamilton Families shelter in the Tenderloin. Bates enrolled in CalWORKs, landed a two-day-a-week job and was offered a rent subsidy through Compass.

Finding Home Beyond S.F.

She hunted for apartments, in San Francisco and beyond, that would accept tenants with rent subsidies. Eventually, “by the grace of God,” a friend told her about a one-bedroom apartment in Vallejo and gave her the landlord’s number. The next week, she and her daughters moved in. She pays just $220 of the $1,295 monthly rent; the balance is covered through her subsidy.

Bates is taking social science classes at Laney College in Oakland and hopes to transfer to San Francisco State University to get certified to work in community mental health. She misses the city, she said, but not too much – and especially not living in the Tenderloin.

“That’s not a place to raise kids, always stepping over feces and needles,” she said. “I would like to be in San Francisco, but now that I’m in the East Bay, my kids are more calm.”

Several families who stayed with Bates at Hamilton also got subsidies and all of them left the city. “People just wanted to have a place,” she said. “They went as far as Stockton or Sacramento. Some were sad to leave and some were ready to go.”

The thrust of the report — that most families are being housed out-of-county, jeopardizing their ability to maintain housing and employment — was echoed in interviews with agency leaders.

Difficult Conversations With Families

Most families moving out of the city have longstanding connections here that are being severed, causing them to leave behind “churches, synagogues, community connections, child care and families to watch kids,” said Devra Edelman, Hamilton Families’ director of programs. These considerations trigger difficult conversations with agency counselors, she said.

“Our housing service specialists, they pull their hair out quite a bit,” Edelman said. “They have to explain to families, ‘If you’re going to exit homelessness and stabilize back into housing, it’s most likely you won’t find housing you can afford in San Francisco. You’ve been here all your lives and now the only place I can find for you is in Stockton.’ And the families are like, ‘Where’s Stockton?’ It’s tough for both the family and the staff.”

Since people get paid more to work in San Francisco than outside the city, they end up grappling with a difficult calculation, Edelman said: “What’s the balance between getting paid less in Fairfield and more in San Francisco?” The farther they move, the greater their challenges and the more likely they are to return, homeless, to the city after their subsidies run out, she said.

‘Downside of Living in a Capitalist Economy’

Kositsky said families are opting to leave the city, as people with varying incomes do all the time. “I don’t consider it displacement,” he said. “I don’t have any problem with it at all.”

San Francisco has created more permanent supportive housing for homeless people per capita than any other U.S. city, Kositsky said, “but we can’t build all of the social housing in the Bay Area that’s needed. I wish we could.”

“In my heart, I want there to be a universal housing subsidy for all people making below 35 percent of area median income,” Kositsky said. “But until we have that, we’ve got to do this rationing. The downside of living in a capitalist economy that doesn’t produce enough housing for poor people is that you have to ration.”

Tomiquia Moss, who replaced Kositsky as chief executive officer of Hamilton Families in July 2016, is concerned about the toll relocation is having on homeless families and on her staff.

“We stabilize you, get you into shelter and counseling services, get your kid in school, help you think about budget,” Moss said. “Families start feeling OK. They start looking forward. Then a family rehouses outside of the county, and that process starts all over again. People get destabilized because they have to relocate.”

New Measures to Boost Family Support

Hamilton is taking steps to bolster families who move outside the city by tracking them for two years and setting up a text-messaging system to stay in closer touch with them after they leave the rent program. The agency is also contracting with Urban Institute and UC Berkeley’s School of Social Welfare to conduct focus groups and interviews with relocating families.

Still, seeing few other options, Hamilton and the city have doubled down on the Rapid Rehousing approach. Hamilton has almost completed an effort to raise $30 million for its Heading Home campaign, which supports its rent subsidy and housing assistance programs, Moss said. Salesforce contributed $10 million, the city of San Francisco committed $7.5 million, and Airbnb and the San Francisco Giants are jointly kicking in $350,000.

Other Bay Area cities also are confronting the need to relocate homeless families to more affordable cities. A rehousing program in Berkeley is placing 97 percent of homeless people outside that city. Galan’s report recommends that Bay Area cities address the problem regionally, and Moss and Rhorer said they were talking with colleagues in other counties about sharing social workers, satellite offices and case management services.

“This is on the minds of the entire Bay Area,” Rhorer said.

In the meantime, Moss said, it’s better to help families with children find homes outside the city than to leave them sleeping in cars or homeless.

“I don’t like the reality,” she said, “but I want to put as many choices as possible in front of these families.”

Correction, March 9: The rent-subsidy provider for Regina Bates was incorrect in the initial online version. It was provided by Compass Family Services, not CalWORKs.

An abridged version of this article appears in the Spring 2018 print edition of the Public Press, which can be bought at select retail locations.