San Francisco has begun rolling out a new technology platform that officials say will better help the homeless population by giving priority for shelter and housing to those with the greatest need. But by formalizing who has priority — and who doesn’t — the system also functions as a form of rationing of the city’s scarce affordable housing.

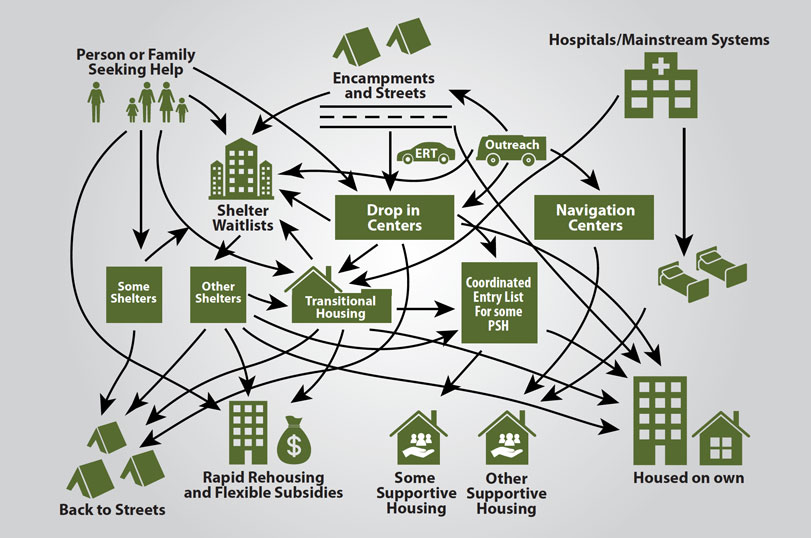

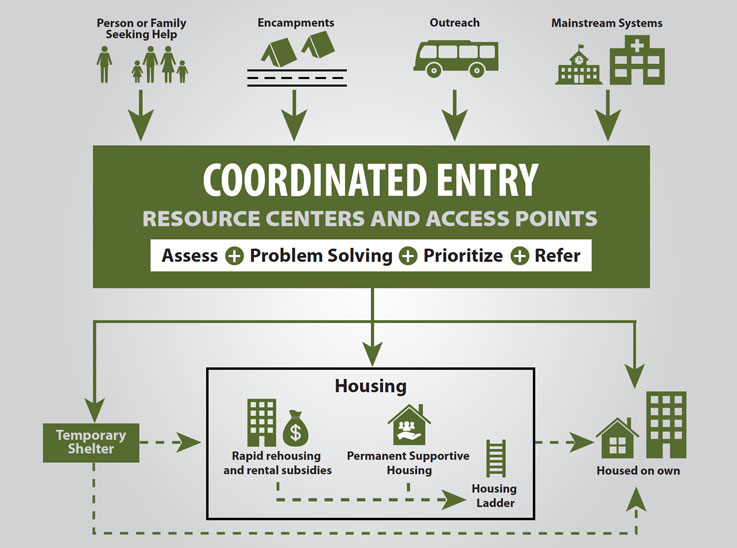

The new approach, known as coordinated entry, aims to replace a disjointed and cumbersome system that has forced people to visit programs scattered around the city, repeating their stories over and over to get help. It creates a standardized process for conducting intakes and evaluating needs, and designates two sites to handle the intake process for all families.

The new $4.9 million Online Navigation and Entry System merges 15 databases into one that tracks all people served by the city’s homelessness programs. Implementation began in June with families, and the city aims to expand to single adults by this summer and youth by the fall. That would fulfill a mandate outlined by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development in 2013 for cities receiving federal grants to address homelessness. Several other localities, including Santa Clara County, Los Angeles and Seattle, have deployed similar systems for several years.

The coordinated approach will enable the city to break through the backlog of families cycling in and out of shelters, transitional housing and their cars as they wait months to get into housing, said Jeff Kositsky, director of the city Department of Homelessness and Supportive Housing. “We’re moving towards a system in which we can see everybody who’s in the system, what their needs are, and prioritize people,” he said.

For example, families living on the street, experiencing domestic violence or staying at shelters that provide only sleeping mats on the floor are deemed higher priority and get first crack at moving to a better shelter or supportive housing. To gain access to services, families must first approach either of two official access points, one run by Catholic Charities in the Bayview neighborhood, the other run by Compass Family Services on Market Street.

‘A Step in the Right Direction’

Local service providers and advocates generally support the concept, largely because the process of seeking shelter and housing from multiple organizations has been haphazard.

“Coordinated entry is a step in the right direction,” said Lenine Umali, director of external affairs and policy for Compass Family Services. “Prior to this, the system wasn’t working. Families had to tell their stories and relive their traumas over and over again” each time they went to a different service provider, she said. “Now, they tell their story once. It’s locked in and everyone has access.”

The initial rollout of the ONE System, developed by Las Vegas-based Bitfocus, was hampered by software problems and confusion about which families are deemed a top priority. Jennifer Friedenbach, executive director of the Coalition on Homelessness, said some families are being excluded from getting moved into shelter or supportive housing. Families who have squeezed into the apartments of friends or family members or scrape together enough money to temporarily pay for a hotel room are considered low priority and are unlikely to get housed.

“They are prioritizing families who are on the street,” Friedenbach said. “That creates a perverse incentive for families to stay on the street. We don’t have enough housing or shelter, and this is basically a system to figure out who among all the people desperate for a place to live gets to be the lucky ticket winners into housing.”

‘Not a Place to Raise a Kid’

The new system may keep Amy Hampton, Dempsey Jackson and their 5-year-old son stuck in the small room they’ve been sharing for almost three years at the Knox residential hotel on Sixth Street. They have no kitchen and share a bathroom with other tenants down the hall. Mouse droppings litter the floor behind their small refrigerator.

“We have bedbugs, roaches, mice,” said Hampton, 38. “It’s not a place to raise a kid.”

Both parents have struggled with addiction, and each has been clean for more than five years. Hampton has a full-time job as a janitor, earning minimum wage, and Jackson gets $900 a month in Social Security disability payments for post-traumatic stress disorder and other medical complications. Between them, they take home about $2,500 a month and pay $700 in rent.

Before moving into the Knox, they were living separately at different transitional programs. Then caseworkers at Hamilton Families approved them for a rent subsidy and they searched, unsuccessfully, for an apartment.

“We never got a call back,” Jackson said. “No one wanted to rent to us.” After three months, the subsidy expired without ever being used.

Their son is in kindergarten at Bessie Carmichael Elementary School and is having a hard time in school and at home. “He doesn’t have his own room or area, and there’s no room to play with his toys,” Hampton said. The cramped quarters make for a lot of tension, “with everybody in everybody else’s business.”

Even worse, “he’s got bug bites, and we all wake up every night from the bugs and the mice,” Jackson said. “He acts up in school, and the teacher admitted to giving up on him.”

Jackson went to the school and met with his teacher and a social worker. Both expressed concern, and the social worker wrote a referral to the Hamilton program, encouraging it to help the family get housed.

The Catch-22

“Family is currently living in SRO with bedbugs, mice and cockroaches,” the school social worker said in her referral. “The child … is having trouble at school when others get too close to him.” She urged Hamilton to help the family obtain better housing for the sake of his “social and emotional development.”

Jackson took the note to Hamilton, but workers there told him that because of the new system, he needed to go to Compass, the agency designated in the new coordinated entry system as the official downtown access point for homeless families. Under the new scheme, Hamilton no longer takes direct referrals.

But at Compass, his luck was no better. Jackson was told that even though they are staying in a single room, under the city’s new guidelines they are still officially considered homeless. However, because they have a place to stay, the Hampton-Jackson family is not considered a priority for other shelter or housing programs, which go first to families living on the street or in cars, or those experiencing domestic violence or other high-priority needs.

Now, Jackson said, he doesn’t know what to do. The options all seem bad: They can remain in their cramped hotel room and watch their son continue to suffer, or move into a tent on the street for a week so they qualify as high priority under the system.

Umali, from Compass Family Services, confirmed that the city’s guidelines don’t give priority to families living in a residential hotel. She said in an email that she hoped the family would return to Compass “to see if they qualify for other housing opportunities.” But she also added a note of resignation: “Given the housing situation in San Francisco,” she wrote, “this option also takes time and is not guaranteed.”

Indeed, after hearing of Umali’s invitation, Jackson returned to Compass. But once again, he was told the agency couldn’t help him because his family is considered sheltered.

This article also appears in the spring 2018 print edition of the Public Press, which can be purchased at select retail locations.