Results-based ‘Social Impact Bonds’ Offer Funding Model Tying Profit to Success

For homelessness efforts in San Francisco and across the country, Nima Krodel is convinced that “business as usual” is not doing much to decrease the number of people on the streets.

Krodel, vice president of the Nonprofit Finance Fund, argues that traditional contracts between governments and service providers have focused too much on short-term activities — hours of case management conducted,individuals served or housing units being rented.

Meanwhile, among privately run single-room occupancy facilities outside the master-leasing program, around 1 of every 7 rooms has been vacant, according to the most recent data available from the city Department of Building Inspection.

Meanwhile, among privately run single-room occupancy facilities outside the master-leasing program, around 1 of every 7 rooms has been vacant, according to the most recent data available from the city Department of Building Inspection.

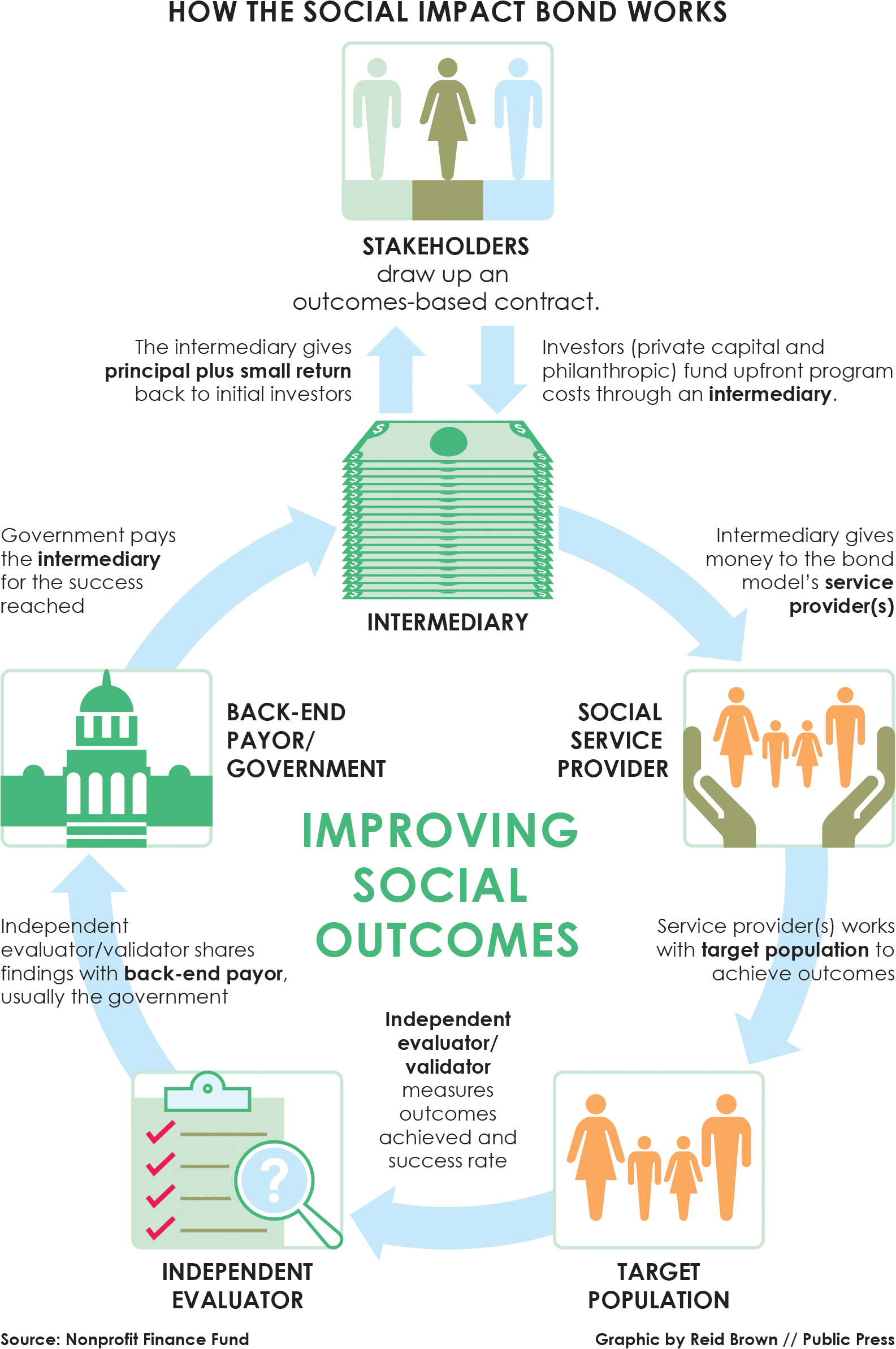

To that end, local and state governments are increasingly experimenting with what are called social impact bonds, a novel “pay for success” model of financing services through private capital. Investors are repaid, with a small profit, only if a project proves successful.

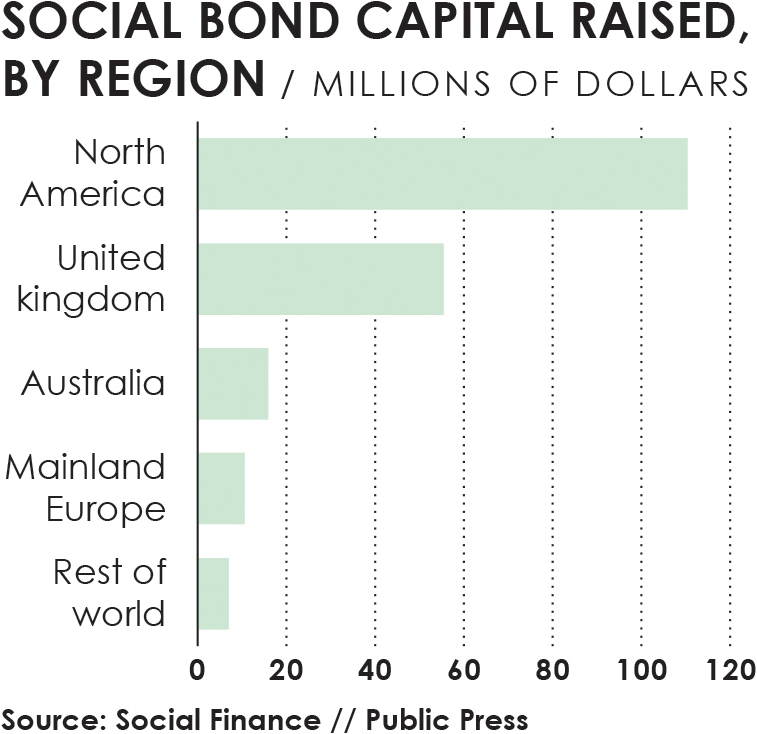

Since their debut seven years ago, these bonds have generated $200 million in the United States and 14 other countries toward programs to reduce homelessness and related social problems. San Francisco could tap into this new funding source to permanently house homeless families, as well as help low-income mothers and at-risk youth, after the city upgrades and unifies its computer systems. Santa Clara County, however, is already experimenting with leveraging private investment to house 150 to 200 people who are among the county’s most costly and chronically homeless individuals.

In 2015, the county raised about $7 million for Project Welcome Home, one of four social impact bonds established as of March 2016 targeting about 1,200 homeless individuals or families in the United States. The others are in Denver (nearly $9 million for 250 individuals), Massachusetts ($3.5 million for up to 800 people) and CuyahogaCounty, Ohio, which includes Cleveland ($4 million for 135 families).

See: Comparing 4 ‘Social Impact Bond’ Projects

The six-year Santa Clara County project emerged after a study of the records of more than 100,000 homeless individuals from 2007 to 2012. The review found that around 2,800 chronically homeless individuals cost the county an average of $83,000 each per year. That was nearly half of all public service costs.

The federal government defines a chronically homeless individual as someone who has been homeless for at least a year or has experienced at least four episodes of homelessness in the last three years, and has a long-term disabling condition.

Project Welcome Home targets these highest-need individuals — the top 5 percent of the chronically homeless — through what is known as a “housing first” model, said Maria Raven, an associate professor in the Department of Medicine at the University of California, San Francisco, the project’s independent evaluator.

Based on a previous housing-first program for a broader group of homeless people, the county’s costs fell 70 percent annually for those who remained housed through the program.

After contemplating the pay-for- success approach, San Francisco determined in a September 2015 feasibility study that it did not have the baseline data system required to track target populations, the types of services needed or outcomes on services provided.

That could change. With the creation of the Department of Homelessness and Supportive Housing and its recent investment in the Online Navigation and Entry System — a unified network to better collect and manage data on the homeless population — the city is closer to adopting a pay-for- success model.

The question is: Will the city turn to social impact bonds to do so?

The Bond Breakdown

Unlike conventional investments, social impact bonds raise private seed money for long-term, innovative endeavors such as keeping the homeless housed and reducing their use of costly emergency services.

Spending tax dollars directly on challenging problems or populations is usually a hard sell politically. What differentiates a social impact bond from other general outcomes-based approaches is the use of outside investors to front direct-service costs. This lets governments test new interventions without digging into their budgets right away and pay only when goals are reached.

The best part, some experts say, is that these bonds align governments, nonprofits and the private sector in a way not seen before.

“The structure links the capital provider much more directly to ‘Are these people’s lives being improved long term for themselves and for the society?’” said Andrew Rachlin, managing director of lending and investment at the Reinvestment Fund, which has invested in homelessness bonds for Santa Clara and Cuyahoga counties. “And we’re at risk, so we’re very invested in making sure the service provider is doing what they say they’re going to do.”

The first social impact bond was launched in the United Kingdom in 2010 to keep ex-offenders out of jail. Since then, about 60 bonds have been implemented across Europe, Asia, Australia and North America.

See: The World of Social Impact Bonds: An Interactive Map

Although the bond model has attracted mainly philanthropic investors, notably the Rockefeller Foundation, it has also opened a pathway for private capital — Goldman Sachs invested in the first U.S. social impact bond in 2012.

In the United States, 10 projects were established by March 2016. One, to reduce recidivism at the Rikers Island prison in New York City, was terminated for failing to show impact. Others target homelessness and early childhood education, with many more in the early stages or still being developed.

With Santa Clara County’s project, investors are paid back as each individual hits certain milestones: being stably housed for three months, six months, nine months and 12 months or more. If someone has a lease but spends time in jail, uses emergency health care or is back on the streets, the success measurement can be paused or restarted, said UCSF’s Raven.

The county is separately tracking changes in the use of public services by Project Welcome Home participants and nonparticipants to determine whether the model can lead to better health outcomes.

If it hits its success metrics, the county will pay investors back a little over the program’s six-year life span — much more doable than providing the payout at once, Raven said. As program participants are weaned off county services, the county can tap into those savings to repay investors. Returns on social impact bonds have generally ranged from 2 percent to 5 percent.

Because the county has a limited budget and cannot commit the necessary funding for an untested project, the use of private capital allows for an added benefit to the service provider: greater upfront funding to target high-need populations with enough case management services and housing.

“Normally, our contracts are starvation contracts. The government tries to give you the very least to get work done without looking at nonprofits’ outcomes,” said Louis Chicoine, the executive director of Abode Services, the contractor for Project Welcome Home. “It’s a cycle where we’re never catching up and having enough infrastructure.”

Further still, as private-sector funding comes with fewer strings attached, a service provider can adjust how and where money is spent, Chicoine said.

“No one was saying, ‘Oh, you could do it for less than that,’” Chicoine said. “This focuses on having appropriately funded nonprofits that have to perform.”

San Francisco’s New Path

Over the years, the call for establishing public-private partnerships that bring in investors other than philanthropic foundations has grown stronger in tech-centric San Francisco.

Although the city is trying to bring its data systems into the 21st century, there are more challenges that are specific to the social impact bond approach.

The contracting process can take over a year as the different sectors decide how to measure success. Because the approach is new and none of the current U.S. projects have completed their terms, there is still no way to compare the success of social impact bonds to previous contracting methods.

As a result, stakeholders say it has been a challenge to encourage private capital to take risks in the social realm, although many recognize its necessity because of the vast resources available in those markets.

Still, they say that more institutional lenders will grow interested as social impact bonds become established and continue to fund programs using proven preventive strategies, such as housing first, rapid rehousing and eviction prevention.

That raises another question: Should private capital remain involved after a pilot project is completed?

Reinvestment Fund’s Rachlin said no, not in investor status. The bond is just a way for the government to make a transition to paying for outcomes, and the private sector should be cut out of the outcomes contract if the project is a success.

“If I have $100 to spend on a social program and I’m not sure it works, it may be worth it to me to spend $90 on that social program and $10 paying an investor’s return in exchange for risk transference,” he said. “But once I know it works, I want $100 worth of social services.”

Others, however, say priorities differ among governments: While some want to get the full bang for their buck through direct contracts with service providers, others may value 100 percent performance-based contracts that require outside investments.

The social impact bond is just one approach to focusing on the long term. Krodel, of the Nonprofit Finance Fund, said the bottom line is that the path forward, whatever it may be, should focus on “outcomes first, approach second.”

“Regardless, it’s about really reorienting lots of different stakeholders into ‘How do we achieve the best outcomes for people in the community?’” Krodel said. The bond “is a piece of that.”

This article is part of the special report Solving Homelessness: Ideas for Ending a Crisis, which appears in the Fall 2017 issue of the San Francisco Public Press.