M ore than 1,200 youths between 18 and 24 years old were unsheltered — living outside, in a vehicle, or in a place not meant for habitation — in San Francisco earlier this year, about the same as the previous biennial count in 2015. As the city steps up efforts to house this nationally targeted population, officials are adapting services used for homeless adults, including navigation centers and rapid rehousing, while looking for new approaches. One proposed solution is based on a simple premise:

Would you host a homeless youth in your home?

“It’s important that we find different ways to access housing in the community,” said Ali Schlageter, the youth-programs manager at the San Francisco Department of Homelessness and Supportive Housing. “This idea of asking community members to open up their homes is something we want to explore.”

“It’s important that we find different ways to access housing in the community,” said Ali Schlageter, the youth-programs manager at the San Francisco Department of Homelessness and Supportive Housing. “This idea of asking community members to open up their homes is something we want to explore.”

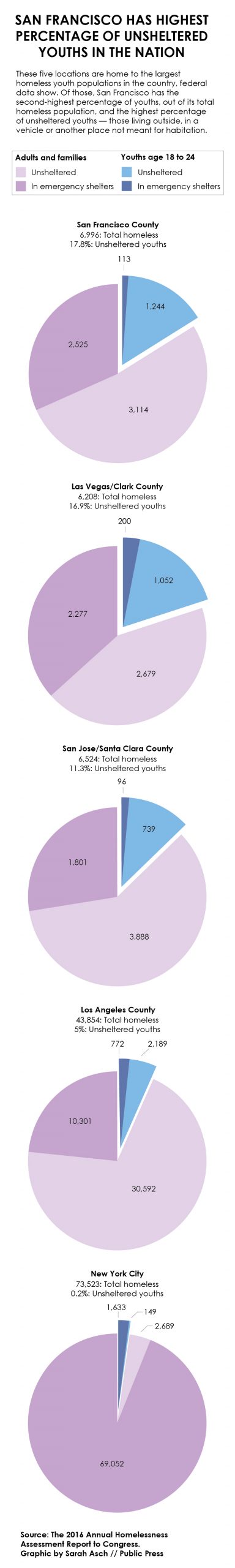

Based on existing programs, this model has shown some success, and it could potentially help the city meet the federal government’s goal of ending youth homelessness by 2020. According to a 2016 report to Congress, San Francisco has the third largest population of homeless youth under 25, behind New York and Los Angeles, but the highest rate of unsheltered homeless youth — nearly 92 percent.

The chronic lack of affordable housing leaves youth few options beyond supportive housing, which is expensive to build and operate. Host homes may provide a small-scale alternative.

How it Works

While many residents may dismiss the idea of taking in homeless youth, there are precedents, most targeting specific populations. The Edgewood Center for Children and Families runs a host home program in the San Francisco Bay Area that assists former foster youth in identifying family or friends to stay with and helps cover the cost. In Minneapolis, the GLBT Host Home Program operates homes for gay, lesbian, bisexual and transgender homeless youth, and they rely on volunteers within that community to be hosts. This offers a potential model for San Francisco, where 49 percent of the homeless youth identify as LGBTQ, according to the 2017 Point in Time count.

Both organizations provide case management to help youth work toward their educational and employment goals. Caseworkers meet with youth in their host homes to help them stay on track to find stable housing after leaving the program, which can last up to several years.

The Department of Homelessness and Supportive Housing is considering funding a pilot host home initiative with some of the $2.9 million grant from the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development to end homelessness among what are classified as “transitional age youth” ages 18 to 24.

Timeline: Efforts to End Youth Homelessness

Stakeholders are debating whether this model, which has a track record, would gain enough traction among youth and potential hosts to get off the ground in San Francisco.

Schlageter, who oversaw the city’s planning process for the HUD funds, identified several benefits of host homes, including that they cost significantly less than supportive housing programs that require the city to pay market-rate rents or employ 24-hour staff.

Edgewood’s program for emancipated foster youth offers an idea of what a bigger host home initiative might cost. The average yearly cost of independent transitional housing in San Francisco is about $30,500 per youth, said Simone Tureck, associate policy director at John Burton Advocates for Youth. But Edgewood’s host home program costs only $16,000 a year per youth, including a monthly stipend for the host, as well as a stipend and case management for the youth, said Cynthia Green, Edgewood’s director of family support.

Schlageter said that by asking people to open their homes, the city could scale up the overall response to homelessness, even if the host home program itself were small, because the housing options for this population are limited.

Edgewood’s program has yielded positive results. A year after leaving the program, 78 percent of the 28 youths who have participated since the program began in 2010 were housed in some capacity: 65 percent as contributing adults in the host family’s home, 10 percent in shared independent housing and 3 percent in another housing program. Only 5 percent were homeless again. The remaining 17 percent could not be located.

The Minneapolis program has also kept the majority of participants housed. Over the past 10 years, nearly 84 percent of the 68 youths who left the program went into stable housing immediately or soon after they left, program manager Rocki Simões said.

The program can only handle 10 to 15 youths at a time, however, highlighting the limited capacity of the host home model.

To skeptics, that is one of the biggest shortcomings. “The host home thing is a small solution to a large problem,” said Christian Calinsky, co-founder and executive director of Taking It to the Streets SF. “There’s at least 1,000 homeless youth and I can pretty much guarantee there’s not 1,000 host homes.”

He also said a host home program would not work for the majority of the youths in his program. As someone with a history of homelessness, Calinsky said that it takes time to work through the trauma of homelessness to the point where a youth could live in someone’s home, especially a stranger’s home.

Recruiting Youths and Hosts

One barrier to growing a host home program is getting youth to participate. According to Calinsky, youth build support networks on the street and often do not want to leave that support system, which is why his program houses groups together. Because a host home program would most likely split up homeless youth, Calinsky does not think many youths would volunteer.

Green said that in her experience with former foster kids, though, she is able to find willing youths because they want to live with familiar figures.

“The most attractive thing about it is getting help with room and board and finding connections with family,” she said.

Recruiting hosts also remains a struggle. Green said that even when the host and youth have a relationship, it is hard to persuade hosts to participate when the county can pay only a small fraction of the cost. The program can pay $500 a month per host family, and “generally in San Francisco room and board costs way more than that,” she said.

Funding is the biggest barrier keeping a program like Edgewood’s from expanding, Green said. With enough funds to hire more caseworkers, Green said she believes this model could work for a wider demographic.

Even with ample funding, hosts must face another hard reality in their desire to help: their guests have likely suffered through some form of trauma.

Calinsky said that the challenge of hosting a youth, especially one who has been on the street or in foster care, can overwhelm well-intentioned hosts, whether they have a relationship with the youth or not.

“You’re taking one of these kids off the street with everything that they have, and I’m not talking about personal belongings. Whether it’s drug addiction, alcohol or trauma, they’re still carrying it around with them,” he said. “The kid might have good intentions and might be an amazing person, but the family is not equipped to deal with that.”

Training Hosts in Minneapolis

The Minneapolis program prepares hosts for the experience with training sessions. The program covers conflict resolution and boundary setting, as well as issues such as race and class.

“The vast majority of queer and trans youth in our program have been youth of color, and the folks who have the resources to step up and help out are often white and middle class,” Simões said, which can lead to power dynamics between youths and hosts the training hopes to address.

The training contributes to the program’s ethos of grass-roots activism. They also root themselves in the community by staying small and avoiding government funding, which can have strings attached. For example, Simões said some of their youths stay in accommodations that would not meet the child welfare requirements, but that are still better than sleeping outside.

“I understand the need to talk about liability,” she said. “But I think sometimes we need to get out of our own way.”

Schlageter said parts of the Minneapolis and the Edgewood programs could work in San Francisco. She also sees the potential for multiple host home programs that target different demographics.

HUD is reviewing the city’s plan, which it must approve before the Department of Homelessness and Supportive Housing can solicit project proposals from service providers. Once proposals are submitted, the Youth Policy and Advisory Committee, comprised of homeless and formerly homeless youth, will help decide which projects to fund.

Service providers who support the host home model are hopeful that San Francisco will implement it. Mollie Brown is the director of programs and community development at Huckleberry Youth Program, an organization that serves youth in San Francisco and Marin. She participated in the planning sessions for the HUD grant and advocated for host homes because the lower cost could expand the city’s capacity to help homeless youth.

“We need to be really honest with ourselves,” Brown said. “If we want to house 1,000 kids ages 18 to 24, how are we going to get it done?”

This article is part of the special report Solving Homelessness: Ideas for Ending a Crisis, which appears in the Fall 2017 issue of the San Francisco Public Press.