Bus Tickets Most Common ‘Housing’ Outcome

In March 2015, as he geared up for re-election, San Francisco Mayor Ed Lee announced the creation of the city’s first navigation center, described as “a pioneering approach” to helping homeless people get off the streets and into housing. He would later call it “a national model.”

Lee billed the navigation center as a place where people would stay for three to 10 days “before moving on to housing or residential treatment.”

Unlike at the city’s shelters, entire tent encampments could enter the center. The homeless could come with their pets and possessions, and they faced no curfews. By getting services on site, they no longer had to trek to government and nonprofit offices.

But what has come of the people who stepped into this novel experiment, in many cases expecting to depart the streets for permanent homes?

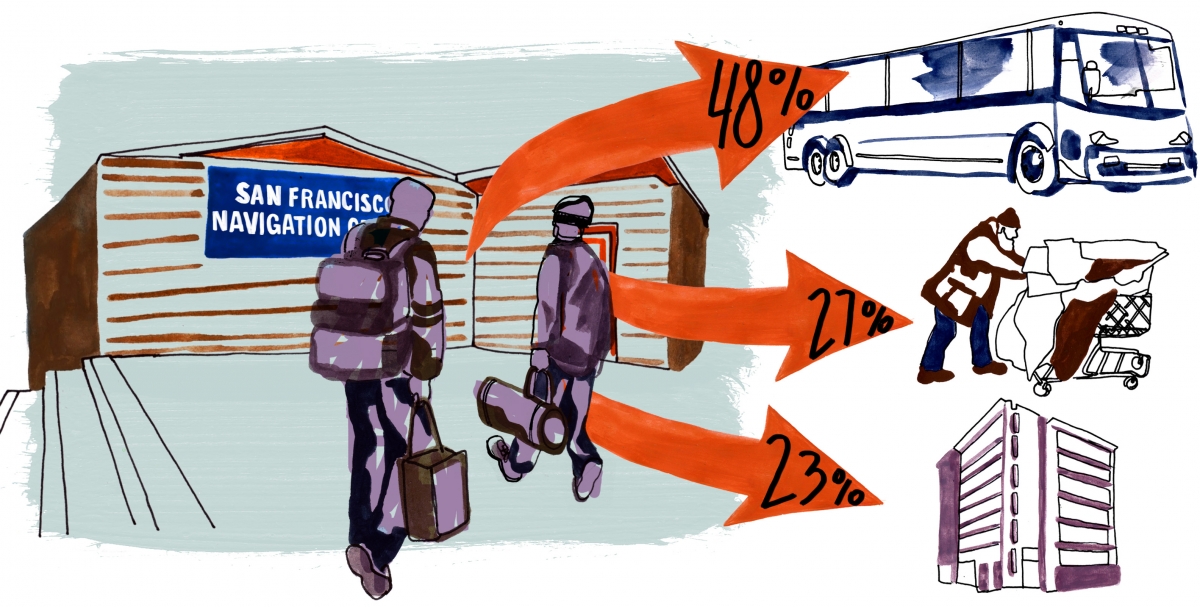

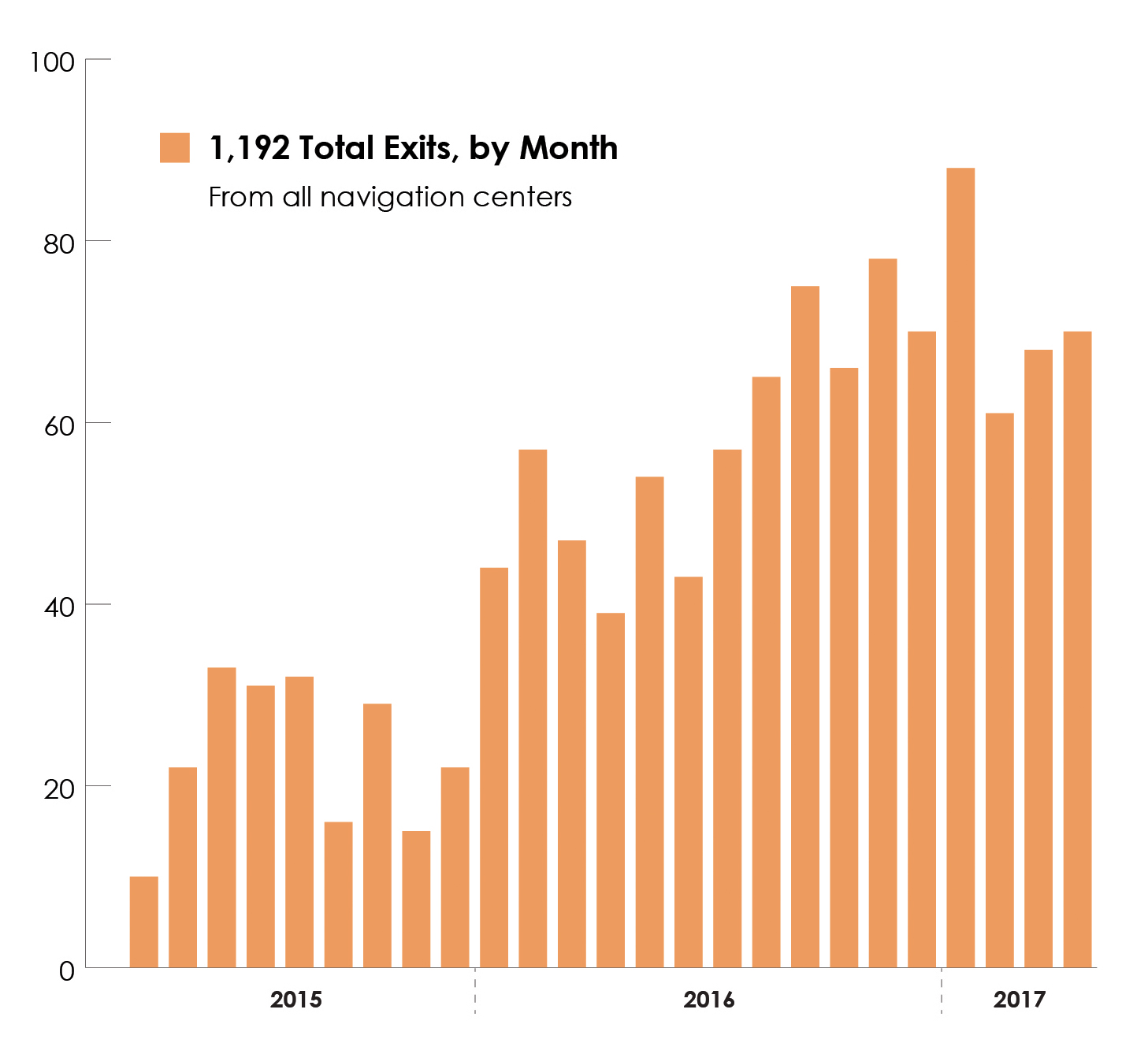

After two years, fewer than a quarter of the nearly 1,200 people who entered the first two navigation centers have been placed in verified long-term housing, a Public Press analysis of city records shows.

Officials, however, have claimed a figure about three times larger. That is because they have been counting people who followed their time at the navigation centers with free bus tickets out of town, supposedly to live with family or friends — but with no guarantee of stability, and minimal follow-up.

Increasingly in recent months, people who stayed at the centers have returned to the streets. More than one-quarter of all who have passed through since 2015 have become homeless again.

Though the original goal of the navigation centers was to transition people into permanent housing, fewer than one-quarter have ended up housed in the city. Illustration by Anna Vignet // Public Press

These outcomes are due in part to management decisions by Jeff Kositsky, the first director of the Department of Homelessness and Supportive Housing, which began operating in July 2016 and inherited control of the facilities.

Lee’s hopes for quick housing placements were wildly off the mark. Rather than days, finding a permanent home was taking an average of three months, and in some cases almost a year, the city controller reported last year.

“The initial idea was that everybody who goes in is going to get access to housing,” no matter how long it took, Kositsky said.

Last fall he imposed a 30-day time limit, freeing up beds the city could then fill with people from encampments that were being cleared, he said. This approach better integrated the centers with other services.

Some providers and activists spoke out against the limit, saying it fundamentally altered the program’s original purpose.

“That’s why it was called ‘navigation’ — it was to navigate people into housing,” said Laura Guzman, who helped manage the first center, in the Mission District, until leaving the post in May.

She said that she knew it would cause her staff to regularly send people back to the streets.

“I was really upset,” said Guzman, who was also director of the Mission Neighborhood Resource Center. “I’ve never stopped voicing my dissatisfaction.”

Bevan Dufty, who as City Hall’s previous point man on homelessness proposed the navigation center, declined to offer an opinion on Kositsky’s move to clear camps more quickly, which shifted the concept away from primarily placing people in long-term homes.

“I’m not going to throw a brick right at this moment,” said Dufty, a former city supervisor who is now a BART board member. “I think in a better world we would focus on housing. But I understand that accumulating that housing is very, very difficult.”

In an interview this spring, Kositsky downplayed the importance of the navigation centers to the city’s overall plans to reduce homelessness. He said he did not want to “obsess over one little piece of the system, because navigation centers do not exit people from homelessness, they’re a path towards that.”

Kositsky said that by the end of July he would publish a multiyear plan for reforming the city’s social services and housing system, with the goal of reducing the homeless population. His team has analyzed 10 years of data to identify which programs, including the navigation centers, traditional shelters or long-term housing units, should be expanded, and to what extent.

How will the city pay for this?

“We’re going to come back in 2018 with a ballot measure,” either a bond or a new tax, he said. That funding would be in addition to the $246 million that Lee has proposed for the department in his latest budget.

$22 Million More

In June, as other agencies faced cuts, Lee proposed giving Homelessness and Supportive Housing $22 million more than the department received in fiscal year 2016–17, which ended July 1. A $5 million cut would come the following budget year.

And yet, for all the city’s money and efforts, the homeless population has risen over 12 years. There were 6,986 adults in 2017, an increase of almost 12 percent from 2005, according to San Francisco’s biennial point-in-time street counts.

Since Lee came into office in 2011, the homeless adult population has grown 8.2 percent. Homeless youths, who since 2013 have been counted separately, fell nearly 44 percent in the past four years, from 914 to 513.

San Francisco’s housing options for the homeless continue to lag demand. Randolph Quezada, spokesman for the homelessness department, said there is enough space in shelters designed for homeless families, and no one is turned away. Citywide there are 1,203 traditional 90-day shelter beds for single adults and 7,066 supportive-housing units, where residents receive medical and social services and are tracked, data from late May show. That leaves thousands without beds or rooms of their own.

In addition to new shelters and supportive housing, the new budget would pay for additional navigation centers. The three that are operating have a total of 232 beds. A fourth center, on South Van Ness Avenue, was scheduled to open in late June, adding 120 beds. It is to close after only six to nine months, as other centers open. By next year, the original Mission center will also close.

The mayor’s office projects that the annual cost to operate all navigation centers will surpass $17 million by 2018.

The San Francisco model has caught the attention of two other cities. Seattle is opening its first center this summer, and the mayor of Berkeley proposed one in March.

The navigation centers may even have international appeal.

“Somebody sent me a photo of a presentation in Dubai where they were talking about navigation centers,” Kositsky said. “How cool is that?”

The Department of Homelessness and Supportive Housing said that in the months after the 30-day limit was imposed, the navigation centers have made headway in getting the homeless off the streets. By January 2017, more than 1,150 “highly vulnerable people” had entered, “and 72 percent of these guests have exited to housing,” according to a statement.

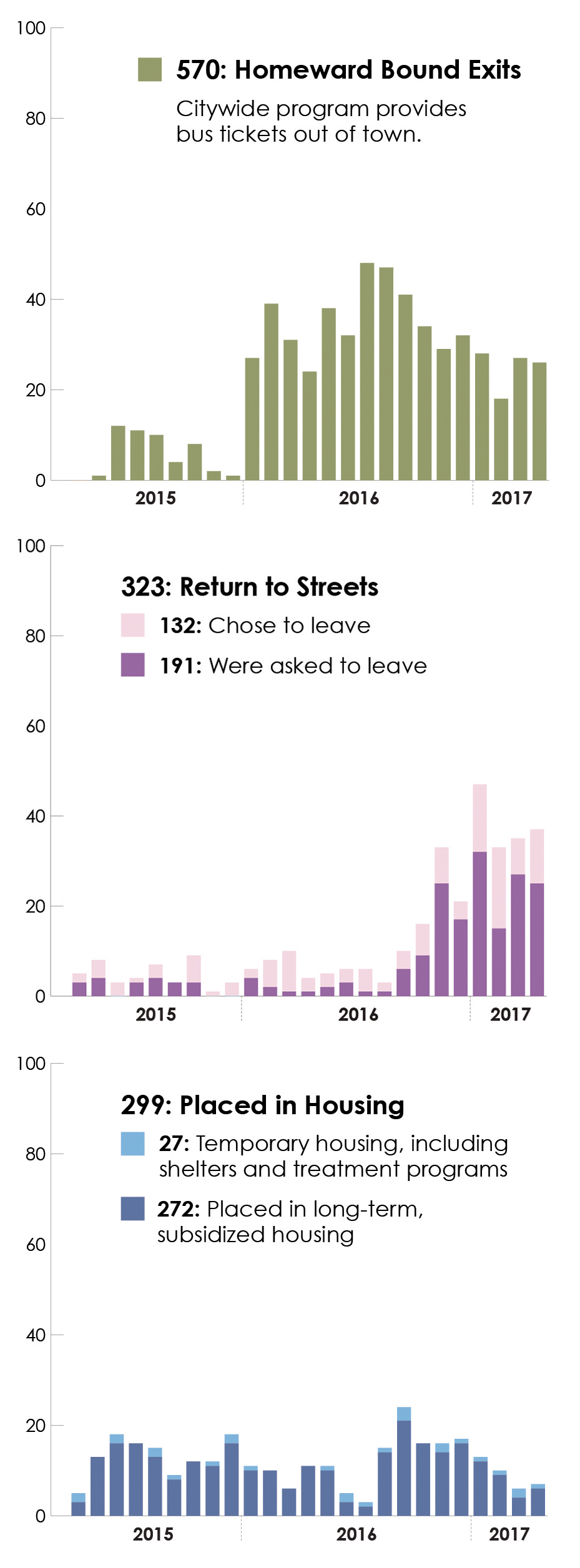

But that statistic contains a big caveat: It counts people as “housed” if they received one-way bus tickets across California and the country through San Francisco’s Homeward Bound program. If the homelessness department had counted only people who ended up in San Francisco’s long-term supportive housing, then the placement rate would fall to 27 percent.

Homeward Bound, which aims to place homeless people with those willing to support them, is a major component of City Hall’s overall strategy to combat homelessness. Since it was launched by former Mayor Gavin Newsom in 2005, about 10,000 people have used it, typically 800 to 850 people a year.

Effectiveness Not Measured

Tickets go to people whose friends, family or other contacts commit to hosting them upon arrival. Staff make follow-up calls to the hosts in destination cities three times within a month of the arrival date to see if the travelers made it safely. Staff may make additional calls, though they are not required.

By spring 2016, after the Mission Navigation Center’s first full year of operation, the city Controller’s Office reported that 42 percent of clients departed through Homeward Bound. Through April 2017, that proportion had grown to 48 percent — 570 people since the center opened.

Nonetheless, 12 years after Homeward Bound began, the city still does not measure the program’s effectiveness at getting or keeping people off San Francisco’s streets, or whether it has changed over time. Quezada said call data have not been compiled or analyzed.

The busing program is a crucial resource to people in dire situations, Guzman said, but counting its clients as housed would be “an illusion.”

“We don’t know if the people are going into any type of housing that can be permanent,” she said.

Kositsky said his department would soon differentiate in future reports between people who receive bus tickets through Homeward Bound and those placed in housing in the city.

He said the busing program is an asset to the city not only because it can reunite loved ones, but also because it unburdens social service agencies.

“From a systemic level, anybody that we can divert out of our system means that there’s going to be more flow in the system,” he said. “More people get shelter, more people get housing, fewer people become chronically homeless.”

The Homeward Bound staff recently suggested offering free bus tickets to residents of supportive housing, freeing up units for others.

“I thought that was a brilliant thought,” Kositsky said. “Maybe now that they’ve stabilized more and maybe they’re not using drugs, or they’ve got their addiction under better control. Maybe that’s more of a possible thing.”

The department is changing how it tracks and makes referrals for social services delivered to the homeless. Fifteen databases are being combined into one, the Online Navigation and Entry System, over 18 months. That will enable staff to more easily monitor usage trends, and will cut down on the steps clients must take to obtain services, Kositsky said.

When the new tracking system is operational, Kositsky said, he would consider expanding the Homeward Bound verification checks to one year.

“If they didn’t stay housed for a year, then I would say it was not a success, even if they don’t come back to San Francisco,” he said.

Those struggling with homelessness tell personal stories that challenge the notion that busing programs lead to permanent housing. In conversations with people living on the streets, a Public Press reporter heard of instances of some having used similar programs in other cities, sometimes lying to secure free travel.

One such participant is Memphis Lamb, who came to San Francisco seven years ago with his husband through a Boston busing program called Lift. Lamb did not know a soul in San Francisco, so he hired someone on Craigslist to call the program’s staff and pretend that he would house the couple upon arrival.

“It was honestly some strange man that we paid,” Lamb said.

Returning to S.F. Homeless

Kelley Cutler, an organizer at the Coalition on Homelessness, said she often meets people who have used the San Francisco busing program, and end up back in the city, homeless.

“We ask if they’ve ever utilized the Homeward Bound program and a lot of them have,” she said.

From its early days, the Mission Navigation Center was effective at its original mission: giving special attention to the people in encampments and getting them housed. Aside from the people who used Homeward Bound, the center’s guests most commonly ended up in long-term supportive housing, data show.

But in recent months, many more have ended up back on the streets.

A year after the navigation center opened, service providers complained that it was giving former encampment dwellers priority access to that scarce housing, putting everyone who applied through other services and access points at a disadvantage. The providers requested a more level playing field.

That fall, Kositsky instituted the 30-day time limit at the center as part of a strategy to make the selection process for supportive housing more equitable. That fulfilled another goal of his: bringing people from tent encampments into the center more quickly, so they could receive services and camps throughout the city could be dismantled.

“I think that we have a crisis on our streets in the form of the encampments,” Kositsky said. “We know you’re somebody’s son or daughter, and you’re our brothers and sisters, but you can’t make everybody else’s lives miserable. You can’t create unsafe situations, you can’t block sidewalks, you can’t defecate on the street, you can’t drop your needles wherever you want. And grouping together in these large encampments is just totally unacceptable behavior.”

But the time limits caused more people to become homeless again.

“For folks where we don’t have a clear pathway to housing, because we don’t have Homeward Bound for them or we don’t have housing for them, we’re not going to let them stay there forever,” Kositsky said. While people are at the Mission center, they have access to caseworkers, medical services, CalFresh subsidized food, cash assistance — and of course a roof over their heads.

The time limit is waived for people waiting for temporary shelters or other services. In April, the limit was expanded to 60 days, after encampment dwellers told city staff that one month was not enough to get them to leave their tents.

The new Encampment Resolution Team was charged with collecting people’s information over many weeks and preparing them to enter the Mission center, treatment programs or temporary shelters as appropriate. Once at the Mission center, people were screened. Those with serious health problems who had been on the streets the longest were transferred to the Civic Center Hotel, the second navigation center. There they received services while waiting, without time limits, to be placed in supportive housing.

“We want to focus our most expensive intervention on the people who have no other pathway,” Kositsky said, referring to supportive housing.

Shorter Stays, Faster Exits

His strategy paid off. People passed through the navigation centers at a faster clip, with a higher percentage coming from encampments. Monthly exits peaked in January 2017 at 88 people, nearly half from camps.

But the time limit made housing prospects bleaker for everyone else who entered the Mission center. From its March 2015 opening through August 2016, the month before the limit was imposed, 91 people left without a destination noted in city records. Then, from September through April, 232 exited without placement. Staff assume all of these people returned to the streets.

Some homeless people said they were caught off guard by the shifts at the Mission center. In January, navigation center staff gave Elizabeth Kidd and Cheree Munson slots after notifying them and other residents of Box City, a large homeless encampment in the Mission Bay neighborhood, that their makeshift structures would soon be removed.

Upon arrival, they were surprised when staff offered help applying only for temporary shelter beds, not long-term homes.

“I had the understanding that after this we would go into housing,” Munson said, pointing to a large sign at the center’s entrance. “It says it right there.”

“SAN FRANCISCO NAVIGATION CENTER: STREET TO HOME.”

Zachary Benjamin and Liz Enochs contributed to this report.

For more about the navigation centers, see “Neighbors Sound Off on Mission’s 2 Alternative Homeless Shelters” from KALW radio, a San Francisco Public Press partner.