Key developments in American languages, from early U.S. history through the November 2016 passage of state Proposition 58, which ended English-only instruction in California. See How San Francisco Paved the Way for California to Embrace Bilingual Education for the overview, and other stories in this reporting project at sfpublicpress.org/bilingualschools.

| Pre-1800s Bilingual education in German and French exists in Philadelphia as early as 1694. Though bilingual schools are common, the lack of many state and federal laws addressing non-English instruction suggests that they are not controversial.

1839 Ohio passes the first state law allowing bilingual education in German and English. Louisiana passes a similar law in 1847 allowing schools to teach in French and any other language requested by parents, and in 1850 the New Mexico Territory permitsSpanish and English. By the end of the 19th century, over a dozen states pass similar laws, and many localities informally provide bilingual instruction in Norwegian, Italian, Polish, Czech and Cherokee. |

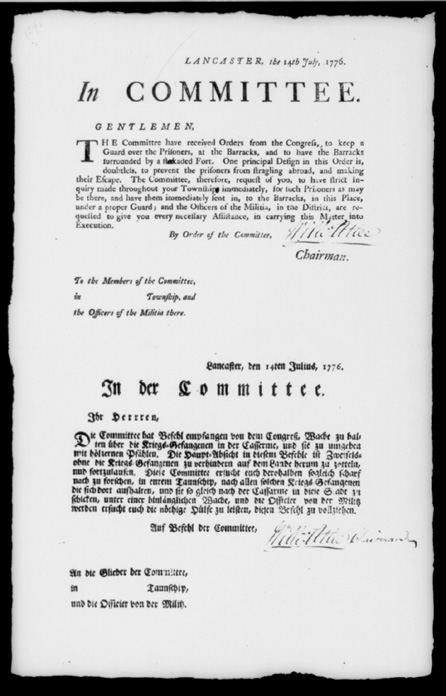

Instructions in English and German for keeping prisoners in Lancaster, Pennsylvania, on July 14, 1776. Image from Library of Congress |

Mission Dolores, San Francisco, c. 1898. Hand-colored image by Detroit Photographic Co. / Library of Congress |

1859 When California officially becomes a state, 18 percent of all education is private and Roman Catholic. Most of these religious schools’ courses are taught by Spanish priests at missions to students who receive bilingual instruction |

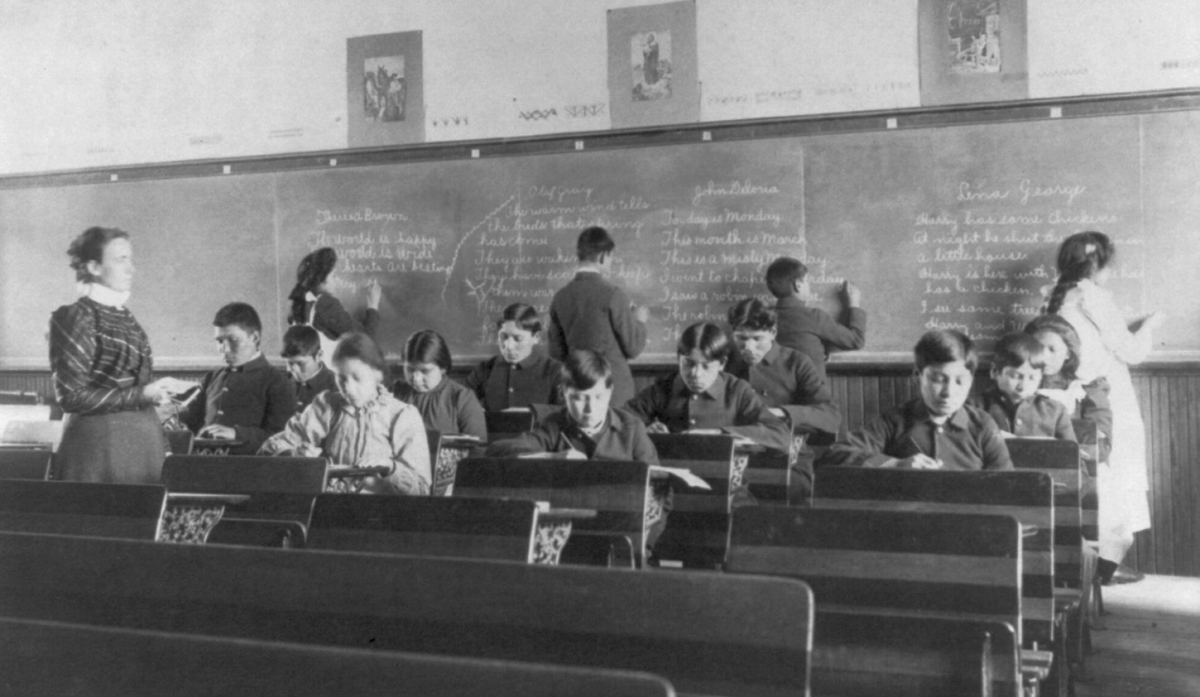

1864 As part of a national policy of assimilation, Congress prohibits Native Americans from being taught in their own languages. Native-American children are forced to attend off-reservation, English-only schools and are punished harshly for speaking their native tongues. “The first step to be taken toward civilization, toward teaching the Indians the mischief and folly of continuing in their barbarous practices, is to teach them the English language,” the Commissioner of Indian Affairs writes, upon ordering English-only instruction.

1868 The 14th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution is ratified. By guaranteeing due process and equal protection, it establishes a constitutional basis for the educational rights of students who are not native-English speakers.

1888 After a backlash against non-English speakers — especially Germans — Wisconsin and Illinois mandate English-only instruction.

WORLD WARS FUEL NATIONALIST, XENOPHOBIC POLICIES

| 1900 About 4 percent of all elementary-school children in the United States are being taught entirely or partly in German. (That’s more than the percentage of students enrolled in Spanish-English programs in the early 21st century.) |  Class in English or penmanship for Native American children at the Carlisle Indian School in Carlisle, Pennsylvania, in 1901. Photo by Frances Benjamin Johnston / Library of Congress |

1906 The Naturalization Act of 1906 requires applicants for U.S. citizen-ship to be fluent in English.1917–1920Bilingual schools, particularly those teaching German, face backlash during and after World War I. Thirty-four states — 15 between 1919 and 1920 — enact laws that declare English as the basic language of instruction.

1917–1920 Bilingual schools, particularly those teaching German, face backlash during and after World War I. Thirty-four states — 15 between 1919 and 1920 — enact laws that declare English as the basic language of instruction.

| 1923 In Meyer v. State of Nebraska, U.S. Supreme Court rules state laws prohibiting foreign-language instruction to elementary students are unconstitutional. Schools begin to lift bans on German programs. |  A pile of German textbooks from Baraboo High School burns on a ; street in Baraboo, Wisconsin, during an anti-German demonstration; near the Sauk County Courthouse in winter or early spring 1918. Photograph by E.B. Trimpey // Library of Congress |

President Calvin Coolidge at a signing ceremony at the White House that included the Immigration Act of 1924. Library of Congress |

1924 Strictest immigration quotas in U.S. history take effect with the Immigration Act of 1924, which excluded Asians and restricted European migration. No limits are placed on immigration from Latin America, but only whites and people of African descent remain eligible for naturalization. |

1930s–1940s As immigration trickles, so does enrollment of non-native English speakers in public schools. Bilingual classrooms dwindle along with demand. The Nationality Act of 1940 replaces the 1906 Naturalization Act but still requires basic verbal English proficiency. As during the First World War, bilingual education is seen as a threat to national security and unity during World War II, with speakers of German, Italian and Japanese falling under suspicion.

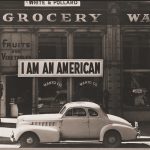

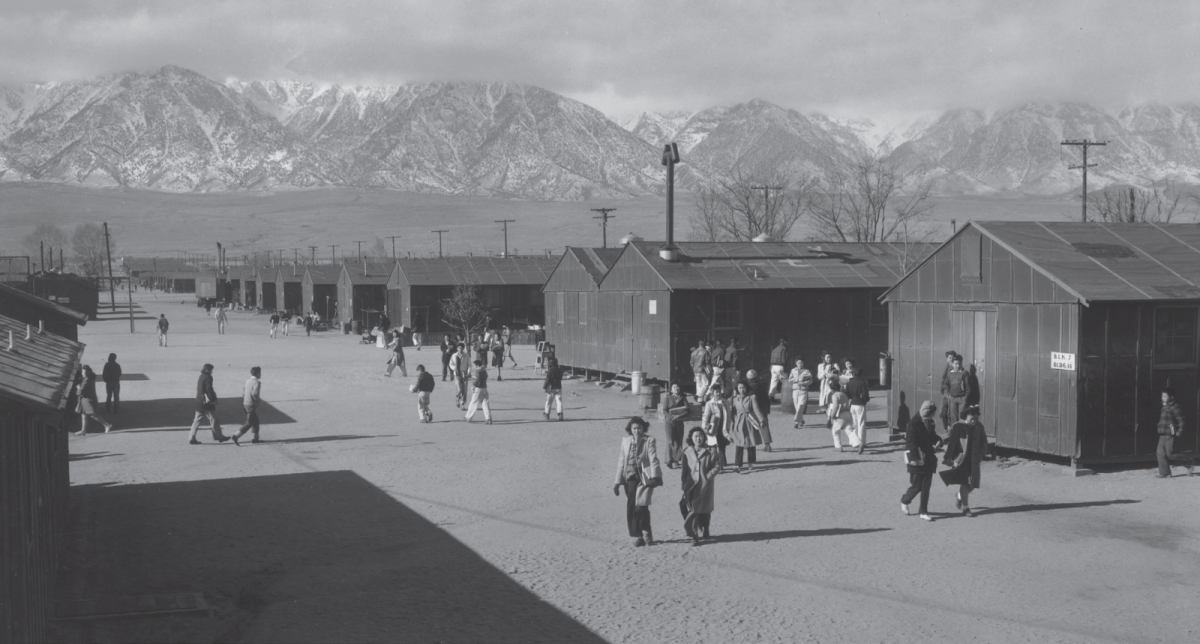

| 1942 Japanese-language schools close after the Dec. 7, 1941, attack on Pearl Harbor. Between 110,000 and 120,000 Japanese Americans are forcibly relocated to internment camps in the Western U.S. |  High school recess for Japanese-Americans at the Manzanar Relocation Center, 1943. Photo by Ansel Adams / Library of Congress |

CIVIL RIGHTS MOVEMENT GIVES VOICE TO IMMIGRANT STUDENTS

|

1950s–1960s U.S. Supreme Court rules in 1954 in Brown v. Board of Education that school segregation is illegal. In 1963, the first large-scale bilingual program since World War II is instituted at a school in Dade County, Florida. The 1964 Civil Rights Act prohibits racial discrimination in all federally funded programs, including public education. Immigrants’ public education enrollment soars. The Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965 ends the quota system based on national origin. |

1968 First federal law on bilingual education passes. The Bilingual Education Act (Title VII of the broader Elementary and Secondary Education Act) mandates that public schools provide students with “limited English-speaking ability” an equal education alongside their fluent peers. It undermines English-only laws in some states. The federal government begins awarding competitive grants to school districts for bilingual programs.

1970 Lau v. Nichols, a class-action lawsuit, claims the San Francisco United School District denied more than 1,800 Chinese students an equal education because of their limited English skills. Though lower courts disagree that education is being denied, the U.S. Supreme Court overturns their rulings in 1974. The final Lau decision says the Civil Rights Act is violated and demands school districts take affirmative action to prevent unfair learning opportunities. “There is no equality of treatment merely by providing students with the same facilities … for students who do not understand English are effectively foreclosed from any meaningful education,” the court’s unanimous ruling states.

1976 In response to Lau v. Nichols, the California Legislature passes, and Gov. Ronald Reagan signs, the Bilingual-Bicultural Education Act (Chacon-Moscone Act), which mandates school districts provide students with equal educational opportunities despite limited English proficiency. The act explicitly declares bilingual education as a right of English learners, replacing Assembly Bill 2284, which offers competitive grant funding but does not require districts to have bilingual Programs.

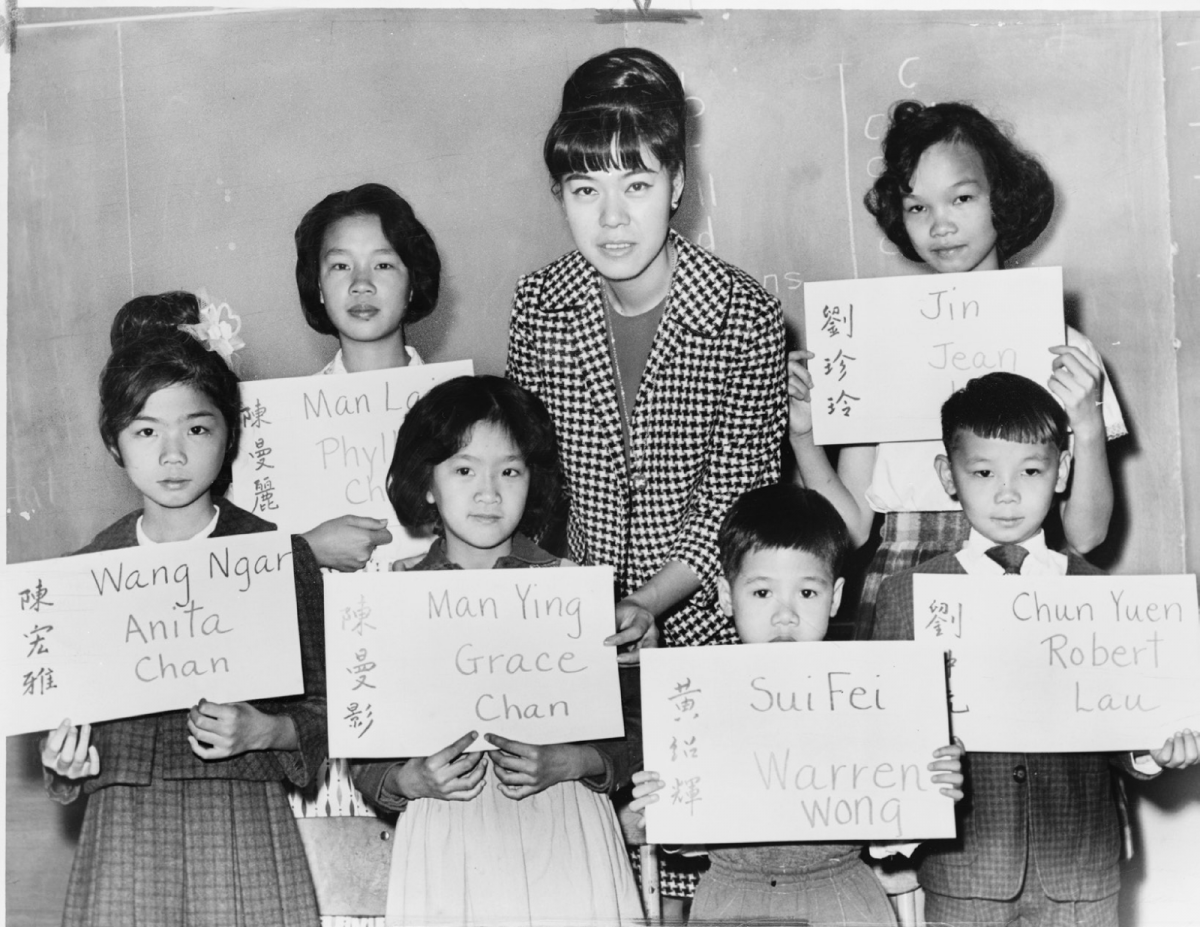

Six Chinese children who had recently arrived in New York City in 1964 with their teacher. The placards show their Chinese names, in ideographs and in transliteration, and the names to be entered in official school records. Library of Congress

1978 Castaneda v. Pickard is filed by a Texas father claiming that his children were placed in a segregated classroom that did not provide “equal educational opportunities” to English learners. In 1981, the Fifth U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals rules in his favor and sets standards for all bilingual programs: 1) based on sound educational theory; 2) implemented effectively with resources for personnel, instruction materials and space; and 3) proven effective in overcoming language barriers after a trial period. These criteria are still used.

1980 California Assembly Bill 507 makes bilingual education mandatory in schools with 20 or more English learners who speak the same primary language and are in the same grade.

CONSERVATIVE PUSHBACK AGAINST BILINGUAL EDUCATION

1981 Declaring them “harsh, inflexible, burdensome, unworkable and incredibly costly,” President Ronald Reagan withdraws the “Lau regulations” proposal from the Carter administration. Those regulations had required schools to offer bilingual education if they were attended by at least 25 English learners who were native in the same language. Reagan considers federally mandated bilingual education an intrusion on state and local responsibility. School districts are permitted to serve the needs of English learners in any way.

1986 Proposition 63, or the “English only” initiative, passes by a 2-1 ratio. This proposition declares English as California’s official language.

1987 Chacon-Moscone Act sunsets under Republican Gov. George Deukmejian. Although existing programs are unaffected, this signals a decline in statewide support for bilingual education. Meanwhile, national interest in bilingual curricula is on the rise.

1988 The U.S. Department of Education presents findings from a four year study showing that bilingual classrooms are just as effective as English-only classes in teaching English learners.

1989 The Ninth U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals rules in Teresa P. v. Berkeley Unified School District that no federal law, including the Bilingual Education Act, mandates that schools offer bilingual programs.

1990 Repudiating past federal policies, the Native American Languages Act of 1990 passes, declaring that Native Americans are entitled to use their own languages.

1994 The Bilingual Education Act is amended to prefer grant applications that develop bilingual proficiency. The U.S. Department of Education affirms the value of bilingualism to both English learners and native speakers.

1997 San Francisco Unified School District institutes a “Language Academy” consisting of four programs: total immersion, two-way development, dual-language enrichment and bilingual. They emphasize the importance of acquiring language skills in English plus one other language. With the exception of total immersion, all these programs are at least partially targeted at helping language-minority students.

1998 California Proposition 227, or “English in Public Schools,” passes with 61 percent of the vote and discourages bilingual classes in most districts. Districts can get around the new law through waivers from parents requesting that their children be enrolled in bilingual programs.

| 2001 No Child Left Behind Act by the Bush administration significantly amends the Bilingual Education Act. Renamed the English Language Acquisition, Language Enhancement and Academic Achievement Act, it replaces the focus of maintaining a student’s culture and home language with an emphasis on English-language instruction and assimilation into regular classrooms as quickly as possible. High-stakes testing is also introduced. |  President George W. Bush signing the No Child Left Behind Act of 2001. White House photo |

2005 A study funded by the California Department of Education on the impact of Proposition 227 shows that there is no significant difference between test scores of students in English-only programs versus bilingual classes.

2010 California adopts Common Core standards to replace the No Child Left Behind Act. Common Core emphasizes integrating language and literacy into content-area instruction. Although the standards imply this will be taught in English, no clause prohibits it from being applied to bilingual education.

|

2011-2013 California sees a wave of bilingual-friendly reform. State Superintendent of Public Instruction Tom Torlakson begins his administration by developing “A Blueprint for Great Schools,” which includes a recommendation to ensure biliteracy through a statewide campaign. In 2012, the California State Seal of Biliteracy, which recognizes high school graduates who are highly proficient in a second language, is adopted by the Democratic-controlled Legislature and signed by Gov. Jerry Brown. |

2014–2016 State Legislature passes Multilingual Education for a 21st Century Economy Act mostly along party lines. The measure would repeal Proposition 227, allowing districts to implement bilingual programs without parents’ waivers. Signed by Brown, it is placed on the November 2016 ballot as Proposition 58, rebranded as the California Education for a Global Economy Initiative. It is approved by 73 percent of voters.

This article is part of an ongoing series on bilingual education in San Francisco and across the state. Funding for this project comes from California Humanities.