When you think about San Francisco’s Chinatown, the first thing that comes to mind might be its art: pagoda-style architecture and dragon-decorated street lamps that showcase the ancient, exotic culture of a civilization half the globe away.

It might surprise you to learn that Asian artists created little of that art, and the works have seldom told the stories of the local community that has lived there for over a century.

In other words, much of the earlier artwork in Chinatown’s public spaces has ironically left Asian American identities and experiences invisible, said Abby Chen, a curator at the Asian Art Museum. That’s largely because the commissioning process included little, if any, outreach to Asian artists.

“We were never part of that,” Chen said. “We were never invited to begin with.”

Sign up for our free weekly newsletter for deep coverage of local communities.

After decades of community advocacy, local groups have increased opportunities for Asian Americans to create public art. And now the city’s Arts Commission and the Chinese Culture Center of San Francisco are expanding that effort by building a catalogue of Asian artists, many of whom might otherwise go unseen, to create future works.

Artists of any experience level can apply online by Sept. 11 to be entered in the Chinatown Artist Registry. Chinese artists who are not fluent in English can email the Chinese Culture Center for help applying.

The initiative is also part of a larger push, begun during the pandemic, to enliven Chinatown through new museums and art spaces, as well as outdoor performances and other events like the night market and the recent Hungry Ghost Festival. Local groups are trying to draw more tourists and citywide residents — especially Asian Americans who might not see themselves represented in typical Chinatown artwork.

“If you’re someone who’s growing up in Chinatown, who has maybe never actually been in Asia or been in China, you would actually [have] a deep sense of alienation or maybe identity crisis,” said Hoi Leung, deputy director of the Chinese Culture Center.

Chinatown has long been a hub for incredible Chinese American artists, including the eminent 20th-century painter Chang Dai-Chien and Tyrus Wong, the artist behind Disney’s “Bambi.” More than 1,000 Asian American artists were active in the neighborhood between 1850 and the 1970s “but we know little of them,” said community historian David Lei.

Often they were unable to break into the professional art scene because they lacked access to typical pathways, Chen said. Many did not attend art schools in this country or have contacts in galleries, and they might have barely spoken English.

Few got commissions to work on public art projects because qualifying processes were “intimidating and complicated,” Chen said. The opportunities were generally publicized in English, so Chinese artists may not have heard about them in the first place and struggled to complete applications within short submission timetables.

By the time judges sat down to choose artists for projects, “We often felt that it was already too late and there were no artists in the pool who could represent us,” Leung said.

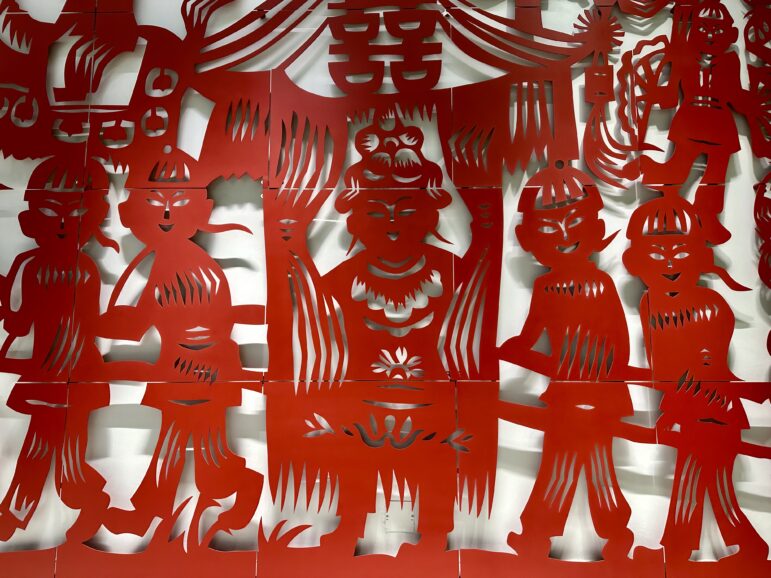

That nearly happened in 2008, when many feared that the commission for the public art project at the Chinatown-Rose Pak Muni station would not go to a community artist. In an unprecedented move, Chen, then working at the Chinese Culture Center, and others at local groups pushed to extend the application period, to buy enough time to find someone with ties to the area. Chen reached out to various artists performing and exhibiting their artworks in the neighborhood and helped them translate their applications.

Jason Winshell / San Francisco Public Press

Details of the laser-cut metal artwork by Chinese artist Yumei Hou, at the Chinatown-Rose Pak Muni station.The strategy worked, and a significant number of Asian American artists became finalists. The San Francisco Arts Commission selected Yumei Hou, a sculptor and traditional paper-cutting artist who lived in a single-room occupancy hotel in Chinatown. Today, a permanent steel fabrication of Hou’s design is displayed at the station, nodding to the Chinese tradition of celebrating the Lunar New Year by decorating homes with paper cuts.

The successful effort inspired the creation of today’s registry, which will retain artist information like their past works and how to contact them.

Artists can apply to be in the Chinatown Artist Registry regardless of where they live or whether they have previous experience creating public art. Applicants must articulate their connection with Chinatown. People can email [email protected] for help applying.

“This is your chance to introduce yourself and your work to the Arts Commission,” Leung said. The Chinese Culture Center is trying to encourage artists to come forward by spreading the word through bilingual media, other Asian American groups and word of mouth.

Members of the Arts Commission and art professionals will place the best applicants in the registry, to choose from when they need artists for public art projects in Chinatown and elsewhere. Three projects are planned at Portsmouth Square, Chinatown Public Health Center and Chinatown Him Mark Lai Branch of the San Francisco Public Library.