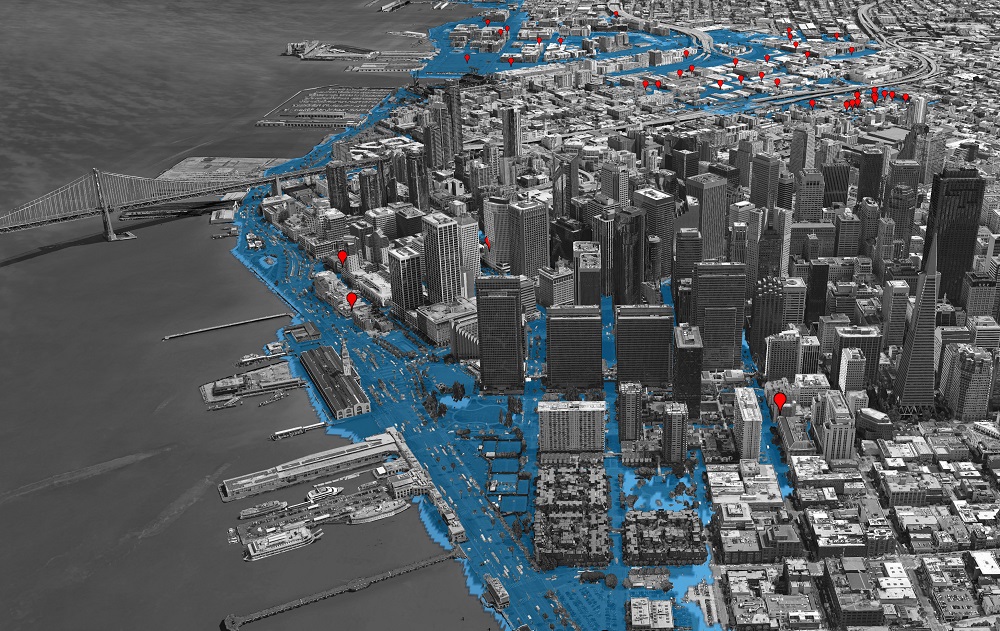

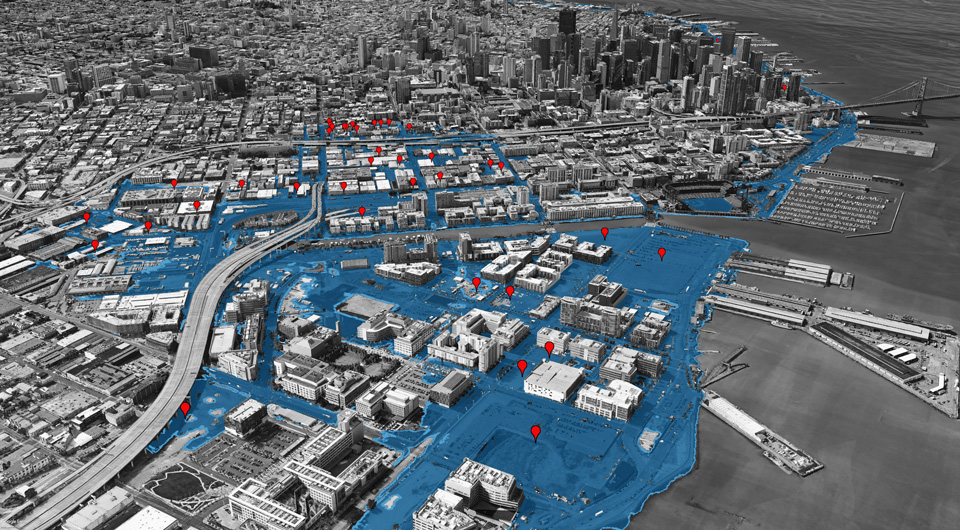

California officials are taking their first, tentative steps toward requiring cities to plan for severe sea level rise that scientists now say could conceivably elevate high tides by up to 22 feet by the middle of the next century. Such a deluge would overtake much of San Francisco’s southeastern waterfront, submerge huge swaths of West Oakland and Alameda, and inundate large portions of cities along the Peninsula and in the South Bay.

As developers continue their scramble to build dozens of office complexes, housing developments and sports facilities bordering San Francisco Bay, a state-funded study recommends that local planners adopt a risk-averse approach to permitting developments such as hospitals and housing — facilities with low “adaptive capacity” — in areas that have even little chance of flooding in the coming decades.

The Ocean Protection Council, part of the California Natural Resources Agency, has published a draft guidance document for coastal cities, endorsing the emerging consensus among climate scientists that accelerated ice melt in Antarctic glaciers means the oceans could rise far more rapidly than studies indicated even a few years ago.

Previous studies found that comparatively conservative scenarios would have devastating effects, with the Pacific Institute estimating 4.6 feet of sea rise would cost the Bay Area $62 billion in property damage and endanger 270,000 people during floods. No one has begun to estimate the effects of much higher sea rise.

That recent science was interpreted last year by a high-level group of scientists convened by Gov. Jerry Brown. The team examined the direct impact to California, and the council folded the recommendations into the new draft policy, updating a previous guidance that relied on a 2012 study by the National Research Council.

Few other states have attempted to craft policy that incorporates the new data from Antarctica. The upper end of those projections suggests that sea levels could rise by more than 8 feet globally and as much as 10 feet in the Bay Area by 2100, not counting additional storm surge.

S.F. Officials Skeptical

Jenn Eckerle, deputy director of the Ocean Protection Council and lead author of the state guidance document, said California must guide cities toward precautionary thinking. “We’re actually taking the number that the scientists have provided, and saying, ‘Listen, these are the places that are at risk,’” she said. “These are the numbers that you should be focused on. We’re actually providing this extra layer and level of guidance that no other state has done before.”

San Francisco officials, while applauding the reference to cutting-edge science, expressed skepticism about the state’s readiness to help cities codify the predictions into local land-use policies.

Chief among the critics is David Behar, climate program director of the San Francisco Public Utilities Commission. Behar organized a working group to evaluate the new projections, issuing a statement that said state projections “do not provide sufficient guidance on how to use them in a planning, decision-making, or adaptation design context.”

Previously: Wild West on the Waterfront

Sea Level Rise Threatens Waterfront Development

The debate in setting effective sea level rise policies across dozens of jurisdictions focuses on how to be fair when telling developers what kinds of land uses will be permitted. The state’s new guidance outlines a complex formula that assigns a probability of occurrence to a range of elevations to which local water levels could rise and the rate at which that might happen. The likelihoods of these different outcomes are based on a range of global carbon emissions scenarios.

According to the guidance document, if emissions continue unabated, there is a 67 percent likelihood that bay waters will rise by at least 3.4 feet by 2100. Previous research had suggested 3 feet of sea level rise was most likely. Just a few inches of water can flood whole city blocks.

There is a 1-in-200 chance that with high emissions, sea levels could rise by 13 feet in 2150. An even more extreme projection places the worst-case scenario for 2150 at 22 feet, though scientists did not have enough confidence in that projection to assign a probability.

“While probabilistic projections are sought proactively by some, in many instances they are arriving on the desks of planners, engineers, and decision-makers who have little background in the methodologies used,” said the statement from Behar’s group, which was endorsed by the Army Corps of Engineers, the U.S. Global Change Research Program and several climate researchers.

They specifically critiqued the mathematical technique known as Bayesian statistics — relying on what is known today based on confirmed data to predict trends that are fundamentally uncertain. This approach “may lead decision-makers to be overconfident about their knowledge of the future,” the report said. “For example, lack of understanding of the true sensitivity of the numbers in the upper-half of the distribution to uncertainties and assumptions may lead to a failure to appropriately consider possible high-end futures,” especially extreme sea level rise after 2050.

In a joint comment logged with the draft guidance, the Public Utilities Commission and the Port of San Francisco said they agree with the spirit of the guidance update but said the Bayesian probabilities were presented without explanation and would be “opaque to the vast majority of decision-makers.”

$23 Billion in Projects Affected

The new guidance will affect billions of dollars of real estate development, including the Golden State Warriors’ basketball arena, Mission Rock and the historic Pier 70. Since 2015, Bay Area builders have invested more than $22.8 billion into waterfront projects at less than 8 feet above high tide, an elevation that could see flooding from rising sea levels and storms by the end of the century, the Public Press reported in a spring 2017 cover story.

Eckerle, of the Ocean Protection Council, said the state is already seeing the effects of sea level rise all along the coast. “Sea levels will continue to rise,” she said. “We’re trying to get people to think about planning for the future, and not just 30 years or 50 years, but way into the future.”

Kristina Dahl, a climate scientist at the Union of Concerned Scientists, said the state predictions are “in line with where the sea level rise scientific community has moved in the last few years.”

“This will affect people’s lives in a few different ways,” she said. “A policymaker or a developer will have an explicit guidance saying, ‘This is how much sea level rise is in your area.’ It will make it easier for people to make well-informed decisions and ideally translate into less risk for homeowners and business owners.”

Dahl said the new policy doesn’t go far enough in some areas. The guidance document does not mention the more frequent, if less severe, “sunshine flooding” — inundation from higher and more frequent tides — that the Bay Area could soon experience.

In July, her group released a report that said the Bay Area would face these kinds of sunny-day flooding events as early as 2035.

The Ocean Protection Council planned on adopting the guidance on Jan. 31, but after comments from San Francisco officials were received, adoption was pushed to March 14.

Strategies for Adaptation

The state’s new guidance includes a checklist cities can use to identify a range of sea level rise projections and evaluate risks of future flooding.

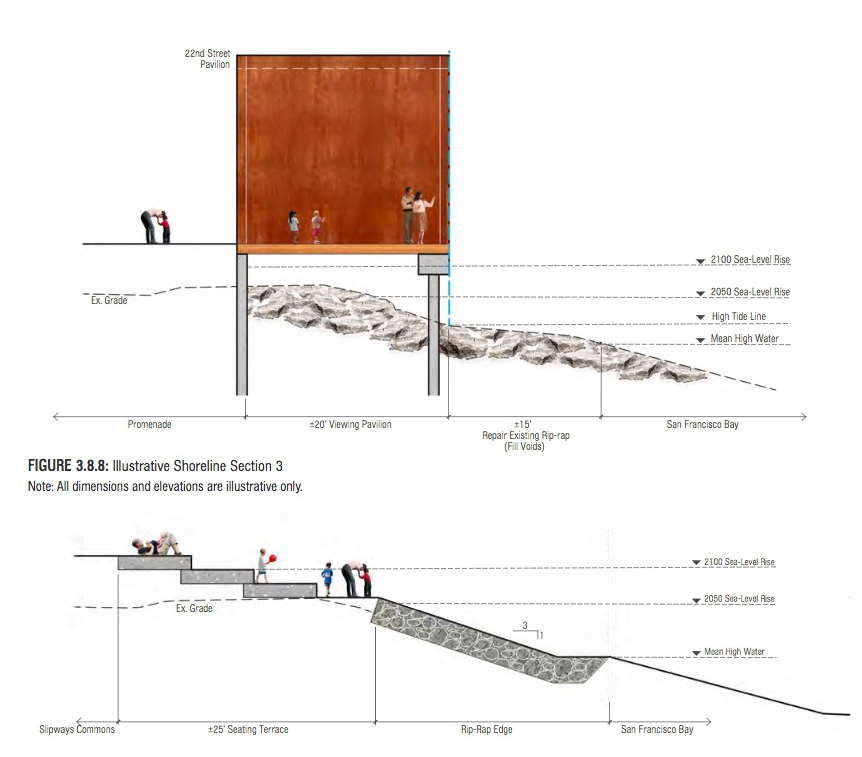

The guidance asks that cities and developers collaborate on regional solutions, such as building wetlands and natural infrastructure instead of concrete seawalls. It also recommends that cities consider allowing the most at-risk neighborhoods to be reclaimed by rising waters.

Policies outlining flooding adaptation and design specifications differ from city to city, and the development plans of some of the Bay Area’s largest projects are evidence of that lack of consensus around the science and how to regulate waterfront land use.

Some plans, like those detailed for the development of a 702-acre neighborhood around the massive Candlestick Point-Hunters Point Shipyard development zone, include surveys of years of scientific papers that describe future sea level rise ranging from half a foot to 4.6 feet by 2100 without detailing a long-term adaptation strategy.

In its final environmental impact report issued in November 2017, developer Lennar Corp. wrote that the estimates of sea level rise vary significantly, and the company outlined a plan to build up the land to protect against 1.3 feet of sea level rise with “a design that is adaptable to meet higher than anticipated values in the mid-term, as well as for the long-term.”

“What is clear is that the science of climate change and sea level rise is evolving, implying that it is prudent to develop community designs that can accommodate various levels of sea level rise over the planning horizon, rather than design to a specific report or estimate,” the document states. The new waterfront neighborhood could have up to 10,000 new homes.

The risk is not only to new construction. According to the Union of Concerned Scientists research, the new eastern span of the Bay Bridge from Oakland to Treasure Island was not designed to be resilient if the bay rose by several feet. The new span opened in 2013, with an estimated life of 150 years. In a white paper, the researchers wrote that 3 feet of rise “will permanently flood the bridge’s eastern ramp” bayward from the toll booths.

Working With Nature

In addition to presenting a synthesis of new scientific studies, the Ocean Protection Council’s guidance documents recommend approaches for addressing sea level rise that emphasize the use of wetlands and other natural barriers.

“While hard structures provide temporary protection against the threat of sea level rise, they disrupt natural shoreline processes, accelerate long-term erosion, may increase wave and storm run-up, and can prevent coastal habitats from migrating inland, causing loss of beaches and other critical habitats that provide ecosystem benefits for both wildlife and people,” the report warned.

Adrian Covert, vice president of public policy for the Bay Area Council, a business group, praised the focus on wetland restoration and said the new projections detailed by Brown’s scientific working group for the Bay Area should be “assumed to be true.”

But he said he’s unconvinced by the notion of “managed retreat,” the idea that neighborhoods threatened by rising waters could be turned into parks or natural areas rather than protected by seawalls.

“The report says that it should be considered as a possibility. No one would disagree with that,” Covert said. “I’m skeptical. It doesn’t take a whole lot of infrastructure to make a managed retreat economically unfeasible. We’re not going to be relocating the city of San Francisco to the Sierra Nevada because of sea level rise. It’s going to require a defense. And the same is true with Silicon Valley. And the same is true with a lot of the East Bay, and a lot of portions around a lot of areas around the bay are going to need to be defended.”

The guidance document asks cities to assess the risk of rising sea levels with online flooding prediction mapping tools developed by the U.S. Geological Survey, Our Coast, Our Future and other institutions. The Ocean Protection Council said these tools “are also helpful aids in communicating about sea-level rise across local, state, and regional communities and planning and decision-making venues.”

Pier 70 Development

The council also recommends developers consider how long buildings will be used. Mike Mielke, the Silicon Valley Leadership Group’s senior vice president of environment and energy, said the guidance document will be useful for local adaptation and restoration planners.

“We’re understanding that we can’t continue to build right up to the bay water line,” he said. “The water line is going to rise, and it’s going to change over time. We have to think about how we are now going to respond to that threat and how we’re going to develop differently.”

In October, San Francisco gave final approval to the redevelopment of a 28-acre former industrial site at Pier 70 that will include up to 2,150 homes, as well as 1.75 million square feet of stores, offices and light industry. The environmental review prepared by developer Forest City in August relied on the National Research Council’s now-outdated predictions for sea level rise of 3 feet by 2100. Those plans might have required changes had they been approved a month later. The approval process is evidence of the breakneck speed at which climate science is advancing and the difficulty local governments have in keeping up with waterfront building standards.

After lower courts chipped away at the long-held interpretation of the California Environmental Quality Act, the state Supreme Court in 2015 overturned decades of land-use law by upholding lower court rulings that cities could no longer require developers to take into account the effects of climate change on their projects. The decision has unsettled public officials and planners, and critics say it will allow real estate interests to saddle taxpayers with a gigantic bill to defend against rising seas.

Steps Toward Setting Standards

Even the Ocean Protection Council’s fresh predictions seem to be superseded by more recent science. In December, Robert Kopp, a Rutgers University researcher and member of the governor’s working group, published an updated prediction that if global carbon emissions from industry remain high, sea level rise could pose a runaway risk by the end of the century. In a blog post, Kopp wrote:

“Consider two roads. One leads to 2 feet of global-average sea-level rise over the course of this century, and swamps land currently home to about 100 million people. The other leads to 6 feet of rise, swamping the homes of more than 150 million. … At least from measurements of global sea level and continental-scale Antarctic ice-sheet changes, scientists won’t be able to tell which road the planet is on until the 2060s.

“But our study also shows that the world can make the 2-foot road much more likely by meeting the Paris Agreement goal of bringing net greenhouse gas emissions to zero in the second half of this century.”

While more detailed science about ice-sheet behavior will help narrow predictions, he added, “decision-makers at all scales — from homeowners to governments — should plan for the future cognizant of this ambiguity.”

The new state effort is not merely advisory. It takes tentative steps toward setting standards for waterfront planning and holding local planners accountable.

Under the Ocean Protection Council’s guidance document, cities will be required to incorporate the new policy into their general plans. The requirement stems from a provision in a 2014 climate bill proposed by state Sen. Hannah-Beth Jackson, a Democrat from Santa Barbara. The bill requires cities to draft their own climate policies by 2022 that reflect up-to-date state guidance on climate issues including sea level rise.

“While some cities and counties have been proactive in developing climate change plans for their localities, many have not,” Jackson said at the time.

Cities Will Bear Heaviest Burdens

A report on climate change policy by the Little Hoover Commission, an independent state oversight agency, said local leadership is necessary because cities will bear the “heaviest burdens of emergency response and recovery during disasters and disruption.”

The California Building Industry Association, which has opposed many state regulations and spent significant resources shooting holes in the California Environmental Quality Act, opposed Jackson’s legislation. In a statement logged with the bill, the association said the state should rewrite its existing flood and fire code rather than require cities to craft climate action plans.

For years, scientists have warned that melting ice sheets and glaciers pose a danger to Bay Area cities. Rising sea levels will cause the San Francisco Bay to expand, threatening neighborhoods across the region.

Shoreline development has boomed in the last decade as more and more people want to live and work near the water. Many residents have moved to the shiny new neighborhoods that have risen out of derelict industrial areas and defunct navy bases along the bay.

Related: Sinking land will exacerbate flooding from sea level rise in Bay Area

Cities benefit from the tax revenue of this development. Politicians see building new homes on marginal lands as an answer to the state’s housing shortage And developers seek the profit and prestige from building high-profile mega-developments, including the headquarters of technology giants Google in Mountain View and Facebook in Menlo Park.

But there is little regional coordination on solutions to the threat of rising seas, and cities disagree about what constitutes the best and most current science.

In the absence of consistent regulation, shoreline development has accelerated in recent years. Bay Area builders are planning to build at least 35 waterfront megaprojects located at elevations that could see occasional flooding at the end of the century, the Public Press has found.

Reporters began a tally in 2015. Besides corporate campuses for technology giants, developments include projects at Treasure Island and in San Francisco’s Mission Bay neighborhood, and an arena for the Golden State Warriors, who are relocating from Oakland.

In April 2017, the Public Press reported that industry groups, led by the California Building Industry Association, pursued a legal strategy to undermine a key provision of the state’s preeminent environmental law that cities had used to help protect their waterfronts.

An abridged version of this article appears in the spring 2018 print edition of the San Francisco Public Press, which is for sale at select retail locations.