The changing climate and shifting weather patterns are affecting each region of the globe differently, and not all coastal cities will experience sea level rise in the same manner.

Even within the Bay Area, encroachment of bay water is sure to require a bigger response in low-lying communities, such as Alviso, near San Jose, than in places that, based on models, are less vulnerable, such as parts of Richmond and Brisbane.

Likewise, there will not be a single most effective adaptation strategy, but many. Broadly, responding to sea level rise requires actions that fall into three categories: fortify infrastructure, accommodate higher water and retreat from the shoreline. Given the economic and cultural ties Bay Area residents have to the water — and because the level of the bay will rise slowly, unpunctuated by the type of hurricanes or cataclysmic storms the East Coast experiences — retreat is a hard sell.

Dikes, Levees and Wetlands

But relying solely on bigger, more numerous “hard” solutions, such as dikes and levees, not only would harm the region’s aesthetic value, but also could undercut the effectiveness of restoring San Francisco Bay’s once-thriving wetlands and marshes — including a massive network of former industrial salt ponds in the South Bay. Municipalities, ecologists and planners agree that robust wetlands are key to adapting to rising sea levels.

If done correctly, wetlands — natural fortifications against the encroaching water — will migrate upland to accommodate the level of the bay, which could rise a foot by 2050 and 5 feet by the 22nd century, according to some projections. For now, planners are using a more modest 3-foot estimate for 2100.

Bay Area residents want to take action on sea level rise. In June 2016, voters approved Measure AA, a parcel tax that will put $500 million toward improving wetlands over the next 20 years.

But unless it is done in combination with other innovative, potentially disruptive baywide adaptation measures, restoring wetlands will be like siphoning a few drops from a brimming bucket, said Nate Kauffman, a landscape architect and urban planning consultant.

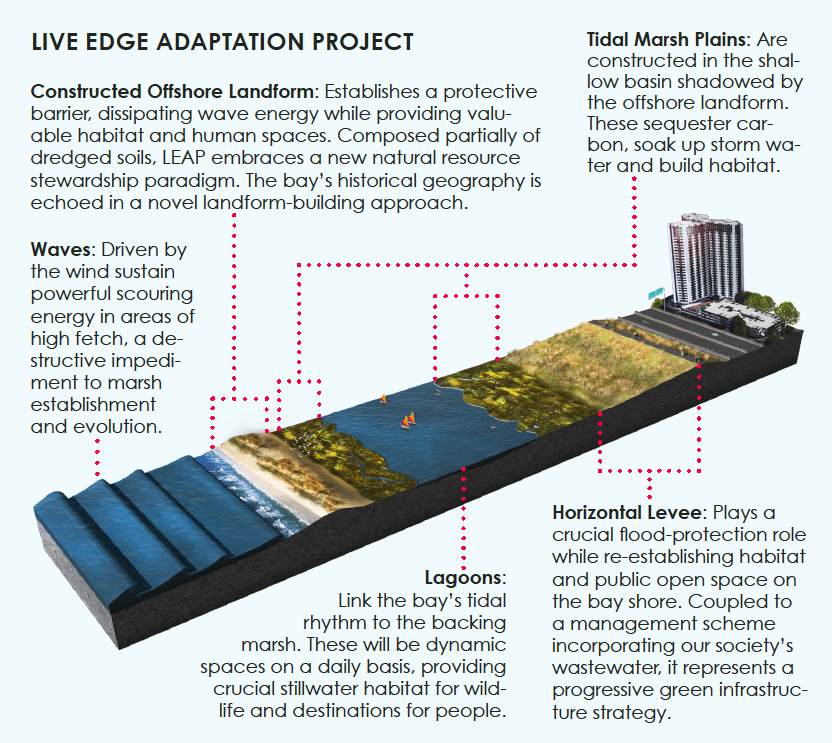

Offshore Landforms

Kauffman’s vision, called the Live Edge Adaptation Project, combines large-scale engineering, such as the construction of offshore landforms that would act as barrier islands and absorb wave energy, with tidal marshes that would form behind them. Leading up to the shoreline would be another engineered landform, such as a wide, sloping levee made of constructed wetlands to absorb storm surges, similar to the horizontal levee project in Hayward.

How could such a plan be achieved? Kauffman said that implementing the plan would have “huge resource and enormous economic implications” but that the concept is also his “vision and argument for a different way of doing things.”

“Systems designed and built 100 years ago are not sustainable, and increasingly less so as we add more people to area,” he said.

Realistic, Affordable Designs

Beginning in April, an incentive program called Bay Area: Resilient by Design Challenge will bring together local governments, designers, planners and other stakeholders to generate 10 design solutions aimed at addressing sea level rise in specific Bay Area communities. The program, inspired by a similar challenge in New York and New Jersey in the wake of Superstorm Sandy, is being underwritten by a $5.8 million grant, led by the Rockefeller Foundation.

Past design challenges aimed at sea level rise have floated audacious ideas, such as building levees across the Golden Gate to separate the Pacific Ocean from the bay. What sets this challenge apart is that rather than starting with design concepts, which may or may not have realistic applicability, it seeks out cross-discipline teams willing to delve into vulnerabilities of localities and communities. The goal is to generate adaptations that are visionary but also realistic, replicable and affordable.

Allison Brooks, who as the executive director of the Bay Area Regional Collaborative coordinates adaptation-planning efforts of four regional agencies, is on the team implementing the Resilient by Design Challenge. She said that until this concerted effort, “local jurisdictions have been attempting, because no one else was doing it, to develop solutions to their sea level vulnerabilities. But we can’t think about issues related to climate and flooding from a jurisdictional standpoint, because climate does not pay attention to city lines.”

The design challenge seeks to tap into sea level rise adaptation and planning efforts already underway, said Brooks, and use strategic plans developed in San Francisco, Berkeley and Oakland as guides. Although the 10 adaptation projects that resulted from the Resilient by Design Challenge on the East Coast are funded through $930 million in federal disaster relief, paying for adaptation in the Bay Area is likely to require capital project funding in the tens of billions of dollars.

Redefining ‘A New Urban Edge’

Gabriel Kaprielian, who directs the Design and Innovation for Sustainable Cities program at the University of California, Berkeley, said how we frame the expensive, complex tasks related to sea level rise adaptation is vital. “Can we think about these problems as opportunities to redefine a new urban edge?” he asked. When it comes to redefining that space, the hardest part might not be designing and engineering, but rather changing policy.

Take, for example, the Port of San Francisco’s 100-year-old, 3-mile-long seawall that runs under the Embarcadero, absorbing the brunt of tides, boat wakes and storm swells. It is far from an adequate defense against rising seas, but remaking it in its current design could mean separating the city from the bay with a large concrete wall. As Gil Kelley, then-director of citywide planning, told a panel on sea level rise last summer, no one wants that. Yet making the port more resilient might mean changing its mandate, Kaprielian said. He endorsed a redesign in which structures along the waterfront are raised, perhaps even floating so they can rise with the tide. Paying for such a change might entail creating public-private partnerships and adding commercial and residential spaces.

Floating Islands, Homes

The San Francisco nonprofit Seasteading Institute is designing futuristic floating islands off French Polynesia, featuring solar power, sustainable aquaculture and ocean-based wind farms.

The project’s pilot islands would cost a total of $10 million to $50 million and house a few dozen people, Randolph Hencken, the institute’s executive director, told The New York Times. And the initial residents would most likely be middle-income buyers from the developed world.

On a smaller scale are so-called amphibious developments. These structures are built on and anchored to land but have the ability to float during periods of high water. Unlike floating cities, these structures are already in use in New Orleans, the United Kingdom and Southeast Asia.

Hope Hui Rising, assistant professor of landscape architecture at Washington State University School of Design and Construction, described amphibious housing concepts to residents of the Dogpatch and Potrero Hill neighborhoods during public workshops in January. She said amphibious housing could be built inside of large levees and, along with open spaces and parks, could help alleviate the compounding effects of coastal, river and inland flooding.

Including Low-Income Areas

Most current Bay Area residents will not be alive at the end of the century and therefore will not know whether adaptations designed for 3 feet of sea level rise succeed or fail. What regulators can do, however, and what Bay Conservation and Development Commission executive director Larry Goldzband considers a priority, is to ensure that adaptations keep all communities safe and that changes made to one part of the shoreline do not harm adjacent areas. “Many of the neighborhoods that exist now along the bay are underserved neighborhoods, low-income,” Goldzband said.

He pointed specifically to East Palo Alto, Alviso, West Oakland, the Canals District in SanRafael, Richmond and Hunters Point. Making sure they are not underserved by sea level rise adaptation plans is a priority for the commission.

In considering environmental justice and the need for baywide solutions, Kauffman said people leading the region’s adaptation efforts should reflect the diversity and needs of the region, which is predicted to add 2 million people by 2040.

Groups that have long been in the vanguard of efforts to protect the bay should accept that they need to make compromises to adapt to rising seas, Kauffman said.

Adding fill to the bay has always been antithetical to groups such as Save the Bay, since the 20th-century extension of the urban shoreline disrupted the functioning of natural ecosystems. But under his concept, filling parts of the bay would be required.

“We’re all going to be way dead before the more dramatic parts of this start to manifest,” Kauffman said, “so it’s easier for those environmentalists to keep fighting as they’ve always been than it is to reinterpret their mission or method for saving the bay. The net effect of all these people trying to protect pieces of the bay will mean that nothing happens and all of the bay is in worse shape.”

RELATED: Q&A With Nate Kauffman

Ellyn Beale and Kevin Stark contributed reporting and research to this article.