This article was updated Nov. 16 and appears in the winter 2019 print edition of the Public Press.

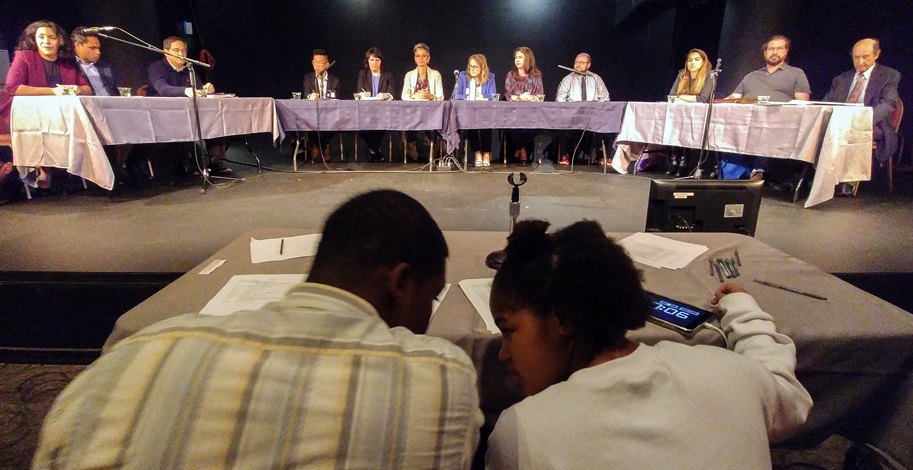

It was another election forum, another school night, and most of the candidates running for the three open seats on the San Francisco school board were arrayed on a stage, facing their two questioners.

But this fall night of ask-and-answer was different. These candidates would be grilled by representatives of the constituents who matter the most in education but who are seldom heard from in the scramble toward Election Day: the students themselves.

Moderators Kierre Garrett and Tyjaya Lynch, both 17, controlled the program that night, firing questions at 12 of the 18 candidates and calling on selected students to ask what was on their minds.

And Lynch did not hesitate to be the enforcer. When candidates, several of them educators, didn’t follow instructions to keep answers brief, she checked them: “Yes or no, please.” When they talked past the time chime, she was the sheriff.

The forum, at the African American Art & Culture Complex in the Fillmore District, was unique in this election season. It was designed and run by members of Youth Council, ages 16 to 24, part of the My Brother and Sister’s Keeper initiative by the San Francisco Human Rights Commission. Questions revolved around how the district could foster equity among schools, how to close the achievement gap — or “opportunity gap,” as some called it — between white and minority students, and how to involve students in key policy decisions.

About 80 parents and students turned out for the forum, which was co-sponsored by Black Young Democrats, Black Community Matters and the San Francisco Public Press.

Racism and Segregation

An audience member asked the candidates how they felt about the “school-to-prison pipeline and its effects on students of color.” Alison Collins, a former educator of 20 years who writes an education blog, answered last. She didn’t mince words. The other candidates had offered ideas for dismantling the pipeline, such as increasing literacy or reducing policing on campus. But none had put a name to the reason such policies were necessary in the first place.

“Systemic racism is a problem,” said Collins, the only African-American on the stage. “If we’re not going to talk about racism — and actually say ‘racism,’ which nobody wants to say — we’re not going to fix problems that are related to racism.

“There are also kids that behave in totally normal ways, and are criminalized for it. Our children are labeled violent, angry, problematic, too loud, I mean, you see it all over the country, right? And it’s happening in our schools,” Collins said. “I’m a mixed-race person, my kids are treated differently, based on the color of their skin. And that’s something that really needs to be talked about.”

With that, the forum had placed its finger on these well-documented facts: The district’s African-American students have long lagged their white and Asian counterparts in scholastic achievement, while exceeding them in suspensions.

Garrett, who attends City Arts and Technology, and Lynch, a student at Raoul Wallenberg High School, underscored fundamental inequalities in the city’s educational system during a series of quick yes-no questions to the candidates.

“Do you believe the curriculum is inclusive of all people’s histories, specifically people of color?”

“No,” the candidates replied, one by one.

“History is written by the rich,” candidate Paul Kangas, a Navy veteran, private investigator and a father of three, interjected.

“Do you think the current student-assignment system has made the schools more segregated?”

“Yes,” they all said.

Segregation is nothing new for the district. The Public Press found in 2015 that the problem was getting worse, but in December 2017 the district reported that the number of schools with more than 60 percent of a single racial or ethnic group had fallen from 22 to 17 schools since 2011. The issue resurfaced last month when school board commissioners called for changing the current assignment system.

Asked how he would close the achievement gap, social worker Faauuga Moliga suggested that schools should open more “wellness facilities,” where therapists, social workers and pediatricians would help students grapple with problems that influence and go beyond scholastic achievement. “Some of these kids and families are coming from really tough places,” Moliga said.

Michelle Parker, former president of the district Parent Teacher Association, said the district should “make sure that all of the children in San Francisco have access to two years of high-quality preschool before they come to kindergarten. We know that that works.”

She also noted that other districts were using an “equity index” to determine how to divvy up money among schools. In their calculations, the districts weigh rates of gun violence and asthma in the surrounding neighborhoods. San Francisco could follow that example, she said.

Funding Inequality Among PTAs

One audience member said “it seems wrong” that some parent-teacher associations raise hundreds of thousands of dollars for their schools while others do not, and he asked how the candidates would address this. (The Public Press reported in 2014 that fundraising provides some schools with supplies and extracurricular programs that others cannot afford.)

Most candidates liked the idea of pooling PTA-raised money from schools and redistributing it based on need — as long as parents were involved in that decision.

Parker said the district could “get creative” about raising money, and she referred to her previous efforts courting corporations to donate to the district.

Phil Kim, manager of Science & Design, Computer Science and Engineering for KIPP charter schools, said he liked the model employed by Circle the Schools, an initiative by San Francisco Citizens Initiative for Technology and Innovation, headed by tech heavyweight Ron Conway, in which “nonprofits and companies actually sponsor schools.” Kim added that it “would be really fascinating to see friendships spring up between schools, who are sharing resources, sharing professional development opportunities, in addition to sharing PTA funds.”

Political organizer Monica Chinchilla suggested trying to solicit contributions from residents who live near schools and “don’t have kids but still want to help. They believe in education and have dollars to spend.”

Throughout the night, there was broad agreement among the candidates about other problems that hamper student equity. They said that teachers should be paid more and receive more staff support in classrooms, and that the district should hire more black and brown faculty.

Involving Students in Policymaking

One audience member, a senior at Mission High School, said that policies on discipline, safety and curriculum are often made without consulting the students.

“What system will you put in place to ensure you are collecting input from students?” he asked.

“Students should be sitting on every district committee we have,” said education consultant Alida Fisher, a mother of four African-American students. “We have parents sit on a lot of them, but students? No.”

Lex Leifheit, who works for the San Francisco Office of Economic and Workforce Development, said that in such a scenario, “I think we need to think about stipends and about paying them for their time.” Other candidates concurred.

Parker suggested that students lead district discussions, emulating some parent-teacher conferences. “I think that makes it much more relevant to you,” she said.

Many other ideas surfaced. “I would love to see students have a seat on the board,” said Martin Rawlings-Fein, a bi/trans parent employed by the University of California, San Francisco. Gabriela Lopez, a teacher at Leonard Flynn Elementary School, suggested that every school have a student representative, similar to how they all have union representatives. Roger Sinasohn, a writer and technology worker married to a city teacher, said that board members could visit schools more often, and that the homeroom period would be an appropriate forum for meeting with students to discuss policy. Collins said the district could also use online polls to get student feedback.

Kim said students should be able to weigh in on district expenditures. “Students should be looking at those budgets and telling us which items are actually making an impact,” he said.

Taking a slightly different tack, John Trasviña, who served as the Department of Housing and Urban Development assistant secretary for fair housing under President Barack Obama, said the district should support student newspapers, because they “can expose a lot of things that are going on within the district, and be a voice for students.”

Importance of Being Heard

What sparked students to take on the challenge of organizing and running a forum?

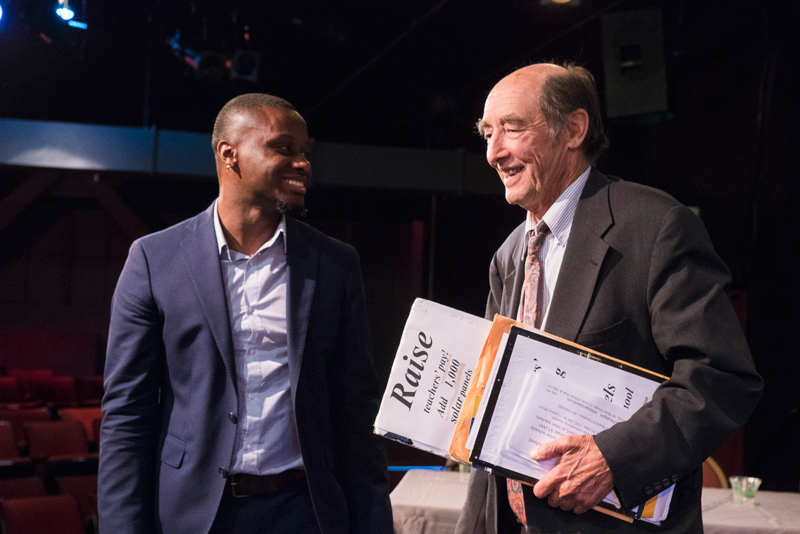

The Youth Council had been playing with the idea of an election event when De’Anthony Jones, a liaison at the Mayor’s Office of Neighborhood Services who works with the council, attended a mayoral forum in May sponsored by San Francisco Young Black Democrats, Black Community Matters and the Public Press. That inspired the Youth Council — which is also the San Francisco Community Action Team for Opportunity Youth United, a national civic-engagement organization — to do something similar to inject student voices into a process that parents and other adults generally control.

“They said, ‘Hey, let’s focus on the school board.’ It’s something they’re directly affected by,” Jones said.

Yolanda Flakes joined the council in part to figure out how to elevate underrepresented voices. She was one of about 15 youths who crafted the event’s questions.

At 17, Flakes’ complex identity gives her a unique perspective into the cultural friction playing out in classrooms. She is African-American and Filipino, raised by her black birth mother, but for the last eight years she has lived with her white foster parents. She spent her first two years of high school at Drew, a private school she characterized as better resourced than Mission High, where she is now a senior. These experiences have shaped the way she speaks and carries herself.

“When people first meet me, they assume something about me, because I’m a black person, but they note something that isn’t stereotypical about me,” Flakes said. “They’ll look at other black people differently.”

She said teachers often discipline other African-American students more harshly than her and her white peers. From her vantage, “looking at it from the outside,” she said that teachers should try harder to listen and make space for students to share how they feel about their experiences and the punishments they receive in class.

“If they were given the chance to explain themselves, the teachers would be able to fix the problems,” Flakes said. “The more and more we’re not able to say what we want to say, the more fueled we are to want to say it. And it just keeps adding up, and adding up, until a bad situation happens. And we get blamed for being bad kids.”

Jones suggested that teachers should employ restorative-justice practices instead of suspending students.

“As opposed to kicking them out, limiting their access to education, we should be giving them an opportunity to actually learn what they did,” Jones said, “giving them solutions on how to self-manage, handle stress. A lot of these teachers don’t realize the kind of trauma students go through at home.”

Jones suggested that the district take this approach at a larger scale by holding town-hall-style events, where school board members could hear directly from students about the problems affecting them.

“I can’t say it can be solved entirely, but it is their job to come up with the solution,” Jones said of the board.

Alison Collins, Gabriela López and Faauuga Moliga were elected Nov. 6. Candidates Mia Satya, Connor Krone, Lenette Thompson, Phillip House, Li Miao Lovett and Darron Padilla did not attend the September forum. Josephine Zhao withdrew from the race, but her name remained on the ballot.