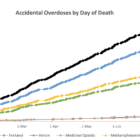

San Francisco’s chief medical examiner delivered grim statistics last week about a recent increase in deaths related to drug use. In the first three months of the year, 200 people died of accidental overdose. That’s up significantly from the first quarter last year, with 142 deaths.

These tragedies were disproportionately suffered by marginalized groups. The biggest increase in deaths occurred among those who lacked housing. People listed as having “no fixed address” accounted for 61 overdose deaths in the first quarter, up from 26 during the same period in 2022. Black residents accounted for 33% of fatal overdoses in the first quarter this year, despite representing only 5% of the city’s population.

Addiction experts say the recent increase in overdose deaths could be linked to the closure of the Tenderloin Linkage Center, a temporary facility that operated in United Nations Plaza from January to December 2022 to help drug users and people without housing access supportive services.

Gary McCoy is vice president of policy and public affairs for HealthRight 360, the organization that ran health services for the Tenderloin site. The center also became an unofficial overdose prevention center, and McCoy connects the rise in overdoses to its closure.

“When TLC was open, and we had a safe place for folks to go, the numbers went down,” McCoy said. “So yeah, it’s pretty telling data.”

Department of Public Health statistics showed that from January to November 2022, the center received 100,000 visits and reversed 300 overdoses. Despite those results, the city shut down the site a month earlier than planned in part due to complaints from business owners and residents who said that drug use and dealing increased after the center opened.

City officials planned to open more supervised consumption sites as part of San Francisco’s 2022 overdose prevention plan, but City Attorney David Chiu advised against this since state and federal laws prohibit them.

Five days after the medical examiner’s report was released, Gov. Gavin Newsom made an unannounced tour of the Tenderloin with state Attorney General Rob Bonta. In a video posted online Wednesday, Twitter user JJ Smith approached Newsom as he strode down Ellis Street, asking him what he was doing about the fentanyl crisis.

“That’s why we’re here. You tell me what to do,” Newsom said as he continued walking.

The health department did not address questions about a link between the closure of the Tenderloin Center and a rise in deaths. Instead it emailed a response pointing to measures the city is taking to address the overdose crisis, including distributing more than 5,000 kits of the overdose reversal drug naloxone and the recent opening of a 70-bed residential facility at Treasure Island for people transitioning out of treatment programs.

State legislators passed a bill last June that would have allowed supervised consumption sites in San Francisco, Oakland and Los Angeles, but Newsom vetoed it in August, saying he would not back such a move “without strong, engaged local leadership and well-documented, vetted, and thoughtful operational and sustainability plans.”

Alex Kral, an epidemiologist with independent research institute RTI International who has been studying harm reduction programs and supervised consumption sites for more than 30 years, called Newsom’s decision “disappointing.” In recent years, Kral provided expert testimony on their effectiveness in public hearings at City Hall and in Sacramento.

“A couple of years before that, when he was campaigning, he said he would sign such a law,” Kral said. “And then he went back on it. And, you know, that was really a shame. And it’s really set us back.”

Kral said he provided San Francisco’s heath department with results of his study of the Tenderloin Center, which showed that it did not increase public drug use or the prevalence of discarded paraphernalia, but that it did reduce drug-related emergency department visits.

Nevertheless, Mayor London Breed expressed disappointment in the Tenderloin Center because fewer than 1% of its clients were provided opportunities to enter treatment.

In December 2021, Breed declared a “state of emergency” authorizing a crackdown on drugs in the Tenderloin. A few months leading up to the linkage center’s closure, police began leaning into a more punitive approach, which Breed lauded in a recent blog post, noting statistics showed that from Oct. 1, 2022, to April 6, 2023, police made 379 arrests for drug possession or sale in the Tenderloin.

But McCoy said the subsequent rise in overdose deaths shows that cracking down on possession is not an effective method for reducing drug use or the harm it causes.

“We’ve increased enforcement, police officers have been arresting and citing people for using drugs and having paraphernalia, the district attorney has increased her punitive efforts,” McCoy said. “And the rates of cases charged for people who use drugs, and our numbers, are going up.”

Furthermore, he said, focusing on the number of people who enter treatment is not an accurate measure of success.

“It takes consistent contact and communication to have those conversations,” he said. “It’s not overnight, although it could be sometimes, but it’s often not.”

During the last days the center was open, people who had been placed in housing and received services returned to express their gratitude.

“They were coming in on the last day, and bringing us flowers and thank you cards,” McCoy said. “It was very emotional.” He said some of those who received assistance were, “upset that what had helped them is no longer going to exist for other people.”

Former client Adriel Cota said the center helped by giving him clean drug consumption supplies. Staff were on hand to reverse overdoses should the need arise. But Cota said he was acutely aware of the perception caused by all the medical emergency activity at the center.

“I know there were a lot of ODs here,” he said. “Paramedics were here almost on the daily but, you know, that’s kind of what this was for. Out of all the ODs I know, everyone survived.”

Cota, who does not have housing, said the center provided him with services that were unavailable elsewhere, were located far away or limited access to once or twice a week.

“Here, every day they had food,” Cota said. “If you would take a shower, they’d wash your clothes, and before you go, get out of the shower, your clothes will be ready. Now, I’ll have to figure it out as best as I can.”

This article is part of a series on San Francisco’s overdose crisis and prevention efforts, underwritten by a California Health Equity Fellowship grant from the Annenberg Center for Health Journalism at the University of Southern California.