Scientists have devised an intricate network of carbon dioxide sensors in the Bay Area that could offer objective measurements to evaluate which climate change initiatives are effective in reducing greenhouse gases in the atmosphere.

The sensors provide real-time local data on how much carbon dioxide is being emitted, said lead researcher Ronald Cohen, professor of chemistry and of earth and planetary sciences at the University of California, Berkeley.

“What we hope the network will tell us is which of the many policies is working,” Cohen said. “It’ll tell us if cap-and-trade is the most effective thing we’re doing or electric cars is the most effective.”

Cap-and-trade, a component of California’s Assembly Bill 32, the Global Warming Solutions Act, uses various tools to reduce greenhouse gas pollution. The program puts an overall limit on emissions produced by oil refineries, utility companies and other emitters. Industries participating in the program receive emission allowances — either the full amount for free, or a set percentage for free and the rest for purchase — that they can then sell on the market if they lower their emissions, creating an incentive for each business to reduce its carbon footprint.

The California Air Resources Board, the agency running the program, will hold the first auction for allowances on Nov. 14.

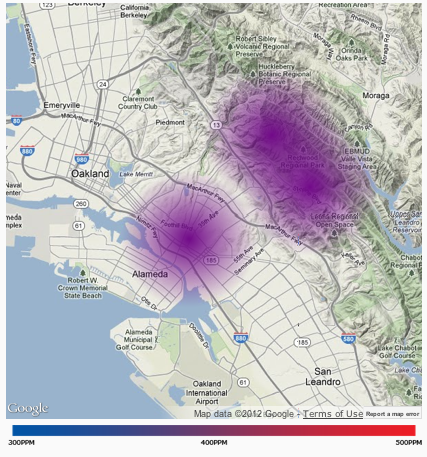

Cohen said his team expects to distinguish among different sources of carbon dioxide pollution, such as the fraction from cars versus that from home heating systems.

The measurements obtained from the network could potentially be used to guide climate-friendly policies, including the promotion of high-density housing near public transportation.

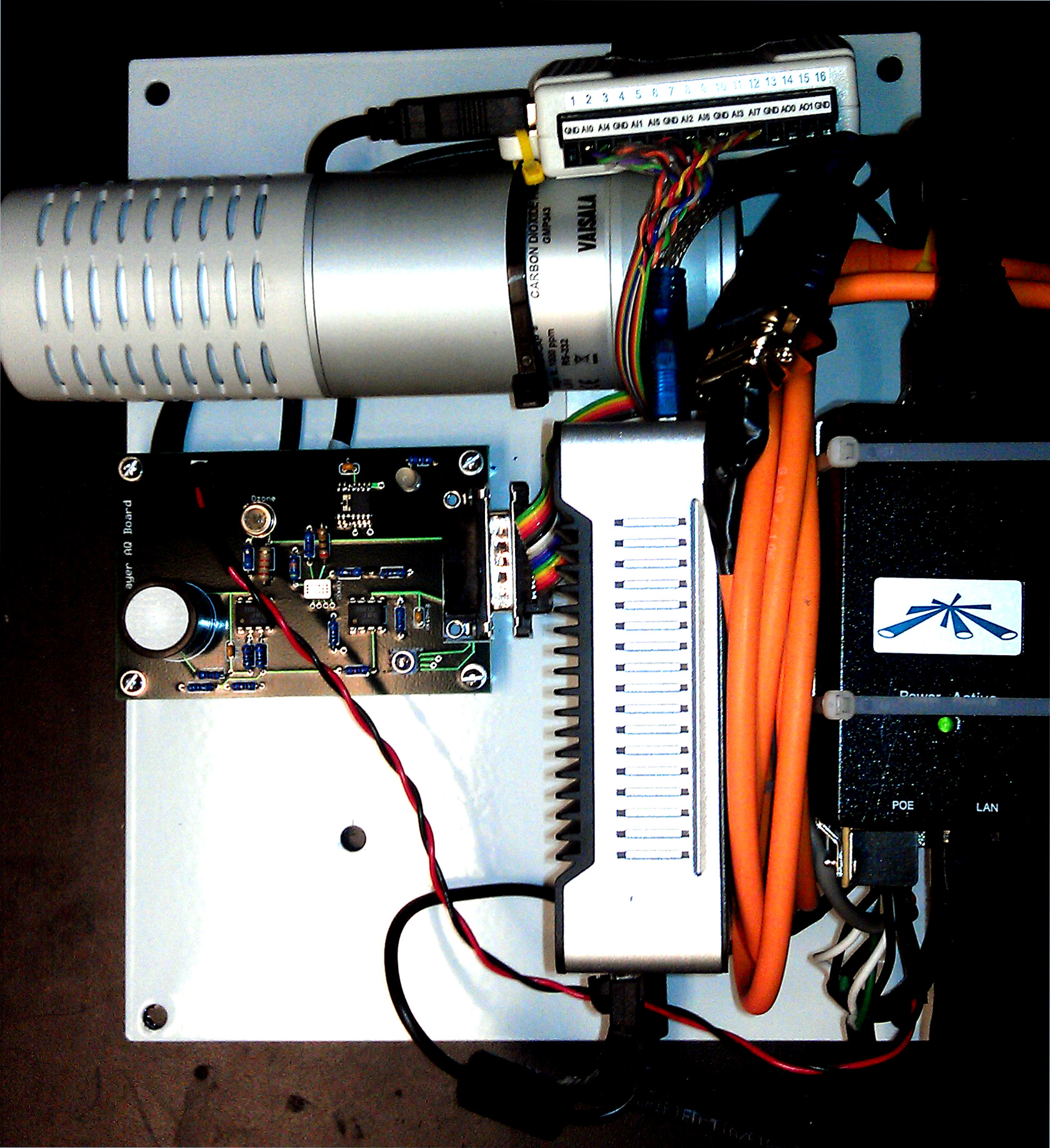

In addition to carbon dioxide, the sensors monitor nitrogen dioxide, ozone and carbon monoxide levels. Data from the sensors is available on the Berkeley Atmospheric CO2 Observation Network project website.

Cohen said the project is unique because of the large number of sensors to be installed across the region.

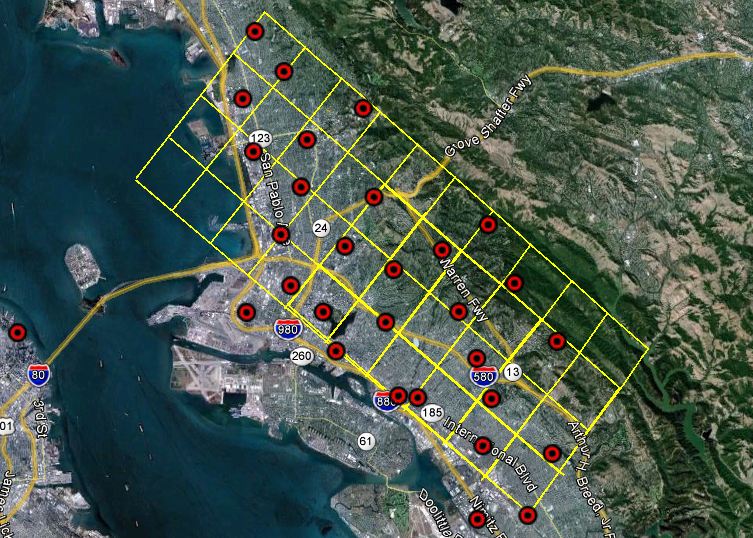

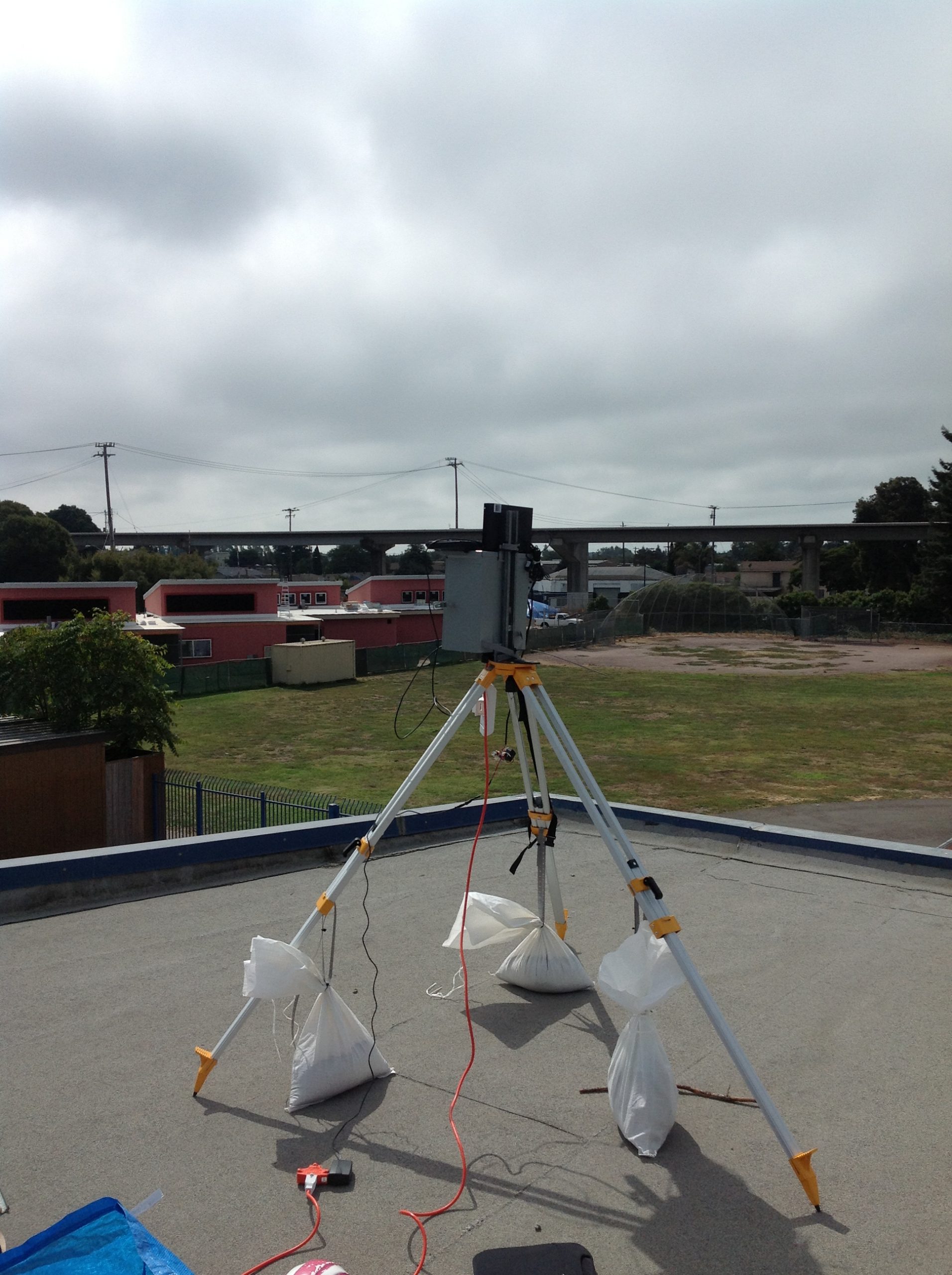

So far only 10 sensors have been mounted, he said, but his team plans to put up a total of 40 in a network extending from El Cerrito to San Leandro. Most will be in Oakland. The sensors cost about $4,000 each and have been installed on rooftops of schools in Oakland with the goal of educating children about atmospheric science and measurements.

Cohen plans to install one at the Exploratorium in San Francisco when it moves to its new location at Pier 15.

The carbon dioxide sensor network is interesting to government officials because the gas has not yet been monitored locally. The Bay Area Air Quality Management District, which regulates air pollution, does not itself monitor carbon dioxide, but tracks emissions of the gas from industry reports, officials at the agency said.

“Carbon dioxide is not technically an air pollutant,” said Eric Stevenson, director of technical services at the air district. “It doesn’t have a direct health impact, so it’s not part of our monitoring network, but we do want to have a picture, because it’s important in terms of climate change.”

The sensors may also prove to be a useful tool for environmental policy planners.

“Generally, we do not monitor air quality at this fine-grained of a scale,” said Laura Tam, sustainable development policy director at the San Francisco Planning and Urban Research Association. “It will be interesting to look at data from this network, once it is built out over time, to see how much variation there is at the city or sub-regional scale.”

Carbon dioxide is the primary greenhouse gas responsible for global warming. Tam said the major impacts of climate change in the Bay Area would be a rising sea level and an increase in extreme weather patterns.

“We’ll see increased hot weather in San Francisco,” she said. “In fact, parts of San Francisco and Alameda counties — because we haven’t really constructed buildings and housing to deal with hot weather — are some of the most heat-vulnerable places in the entire United States.”