Vice President Kamala Harris visited the U.S.-Mexico border on Friday to tour a detention facility and meet with people who have made the journey to the United States. For San Francisco resident Soledad Castillo, who left her home country of Honduras at age 14 to cross the border, the vice president’s visit and her previous statements on immigration have been frustrating, Castillo told “Civic.”

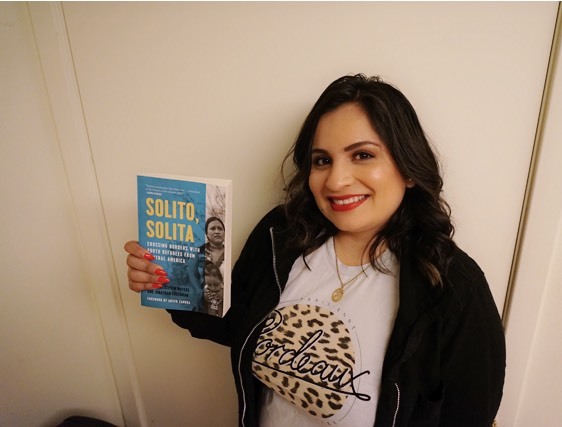

“I’m just so tired of promises and not seeing any changes,” she said. “Kamala Harris went to Guatemala and she said, ‘Oh, don’t come here.’ That was her best. And I was so disappointed because I was hoping more from her.” Castillo is one of the narrators in a collection of oral histories called “Solito, Solita: Crossing Borders with Youth Refugees from Central America,” published by the oral history nonprofit Voice of Witness.

The number of asylum seekers crossing the border has surged recently, with the number of crossings by unaccompanied minors hitting a record high under the Biden administration, according to NBC. The administration has kept in place a policy from the Trump administration known as Title 42, which allowed the immediate expulsion of people entering the country during the coronavirus pandemic, often within hours of their arrival and without any opportunity to seek asylum. The rule has been modified to allow unaccompanied minors and some families with small children to pursue their asylum claims here. Meanwhile, the administration has proposed a $4 billion aid package for Honduras, El Salvador and Guatemala. But Castillo is concerned about corruption.

“We have to think about how corrupt our government is in Honduras,” she said. “So are people going to see the money? I don’t know. I really don’t know.”

Physical and sexual abuse and medical malpractice drove Castillo to travel to the United States, specifically to the Bay Area. But even having survived the grueling journey, she faced additional hardships here. Though she was still a child, she began working double shifts at a laundry the week she arrived. Most of her money went to her father, with whom she lived, and to her family in Honduras. When her father moved away and left her behind, Castillo ended up in foster care with a North Bay family, where she faced near starvation at the hands of her guardians.

“Can you imagine, I’m running away from abuse — from physical abuse, from mental abuse from sexual abuse. And I was never expecting to be abused here in the U.S., too,” she said.

Courtesy Voice of Witness

Soledad Castillo at the U.S.-Mexico border.Because she spoke hardly any English and her social worker spoke no Spanish, it wasn’t until another foster youth was placed in the home and complained about the conditions there that Castillo was sent to a different family, where she was cared for. Upon becoming an adult, she moved to San Francisco, found work, and enrolled in classes at City College of San Francisco. Today, Castillo works as a housing case manager for a nonprofit supporting homeless youth in San Francisco.

She has since traveled to the border and to Honduras to speak with asylum seekers and connect with her family. There, she found that the cost of living in Honduras is oppressively disproportionate to wages. Castillo said her sister earns about 50 cents a day at her job in a mall, but a grocery trip Castillo made for her family on that visit cost nearly $300.

“It was shocking, because I would always talk to my sister. And one thing is talking to them, and another is actually seeing how expensive it is,” she said.

One thing that would help improve conditions for youth arrivals like her, Castillo said, is mental health services.

“I think the major thing that helped me when I came here, and I think it could be better, is just mental health services for undocumented people, which I think is super necessary nowadays,” she said. “I was afraid at the beginning, you know, especially when I didn’t have papers, to go to a therapist. I was like, ‘What happens if they’re gonna give my information to these people? And what happens if I say my full name, am I going to get deported?’ So there’s a lot of fear. And that’s why a lot of undocumented people also don’t seek for support.”

More generally, she said, decision makers and others should hear from immigrants directly.

“Talk to us,” she said. “There’s so many stories that you can hear, and you can have a sense of what’s going on.”