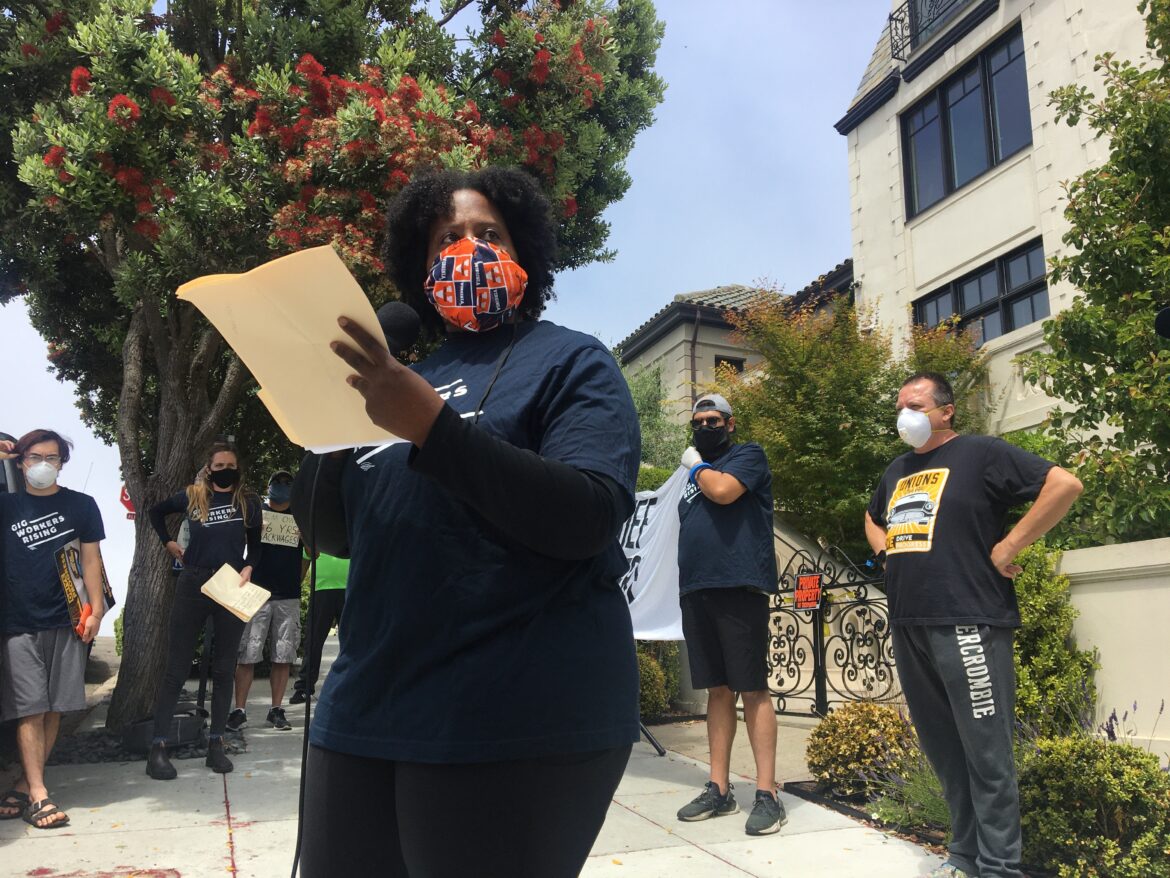

Drivers for apps like Uber, Lyft and DoorDash have said that being classified as independent contractors while working during a pandemic means they face the impossible choice between paying their bills and managing their exposure risk. Cherri Murphy, a lead organizer for Gig Workers Rising, spoke with “Civic” about drivers’ circumstances.

Murphy began driving for Lyft in 2017.

“I felt that it was a godsend, because they offered this whole thing around flexibility,” she said. But that perception shifted quickly. “There’s nothing flexible about not having access to restrooms. There’s nothing flexible about having the looming threat of an accident with no coverage. There’s nothing flexible about me being in the middle of a pandemic, with not having access, particularly in the beginning, of safety equipment. And, you know, those things are really difficult.”

Uber and Lyft have both issued statements emphasizing that they are trying to support drivers throughout the pandemic. Lyft says it has provided tens of thousands of face masks, cleaning supplies and in-car partitions to drivers at no cost to them, and that Lyft does not profit off personal protective equipment it sells to drivers. Uber told Business Insider that it had allocated $50 million toward safety supplies for drivers and had provided 30 million masks and other cleaning supplies to drivers worldwide.

In March 2020, Murphy was completing a doctoral program at a graduate theological union and her primary source of income was driving for Lyft. She decided she would be able to get by without her earnings and chose to stop driving so as not to expose herself to the coronavirus. Others chose to keep working.

“There were quite a few workers that had their backs against the walls, and that were forced to work,” she said.

During that same pandemic, employment law in California changed with the passage of Proposition 22. The ballot measure categorized gig workers — people who work through apps like Lyft, Uber or Instacart or DoorDash — as independent contractors rather than as employees of those companies. Because they are not considered drivers’ and delivery workers’ employers, the companies are also exempt from providing benefits like unemployment protections, minimum wage and sick leave. Drivers and labor organizers have described that system as exploitative, because drivers lack full employee protections and earn less than they should. The Labor Center at the University of California, Berkeley, in an October 2019 analysis of Proposition 22, wrote that while the initiative guarantees drivers 120% of minimum wage, since it only applies when the drivers are actually en route to or transporting passengers, drivers may be paid for only 67% of their actual working time.

Murphy said that in the Bay Area, where the majority of gig workers are immigrants and people of color, the classification of gig workers as independent contractors deepens existing inequities.

“Not only are we in the middle of a pandemic, but we’re also in the middle of a movement that’s been really pivotal as relates to COVID-19 and Black Lives Matter. And so our perspective is that we know that economic justice and racial justice are interrelated,” Murphy said. “At the end of the day, what you have is a law that continues to create a caste system, not designed to have people be economically sustainable, or work in safe working conditions.”