Excerpted from “Latinos and the Liberal City: Politics and Protest in San Francisco.” Copyright © 2019 University of Pennsylvania Press. Excerpted with permission of the University of Pennsylvania Press. All rights reserved.

Fifteen years after the defeat of Proposition R, in June 1994, which set limitations on the conversion of apartments into condominiums, I traveled to San Francisco for the first time. My knowledge of its place in late twentieth-century America was paltry, my sense of its history rudimentary. As a teenager in the late 1980s, I had delighted in sanitized, buoyant images of the city propagated by the television sitcom “Full House.” I had also heard gay people lived there; I do not recall what or who transmitted that information to me. Once in college, a dear friend told me Central Americans had been living in this metropolis for generations and encouraged me to conduct research on the subject. Her revelation piqued my interest, though scholarly investigations were not on my agenda in 1994. The trip would not be a tourist adventure either.

I came to San Francisco to be an activist. That summer, as Californians clashed over the motives and dangers of Proposition 187 — a statewide initiative that sought to deny public benefits, education, and health services to undocumented immigrants — and as San Francisco’s LGBT community commemorated the twenty-fifth anniversary of the Stonewall Uprising, I immersed myself in homeless advocacy work. The organization sponsoring my internship placed me at a Latino homeless project in the Mission, one block east of the 16th and Mission BART station. I could not have imagined that this intersection, the transit system, housing matters, or the city’s Latino population would one day consume much of my professional life.

The Latino community I encountered in the mid-1990s had experienced remarkable developments and continuities since the late 1970s. One phenomenon proved palpable as the 1980s began. In 1981, the San Francisco Examiner reported on what many Latinos were witnessing firsthand: a “new wave of Salvadoran immigrants” had reached the city. What became a twelve-year civil war in El Salvador (1980–1992) spurred a large-scale exodus from that country in the twentieth century’s closing decades. Concurrent armed conflict and economic distress prompted Nicaraguans and Guatemalans to migrate as well. San Francisco became a logical destination for those seeking safety and stability given the long-standing presence of Central Americans there.

One early study found that approximately 15,000 Central American immigrants entered the city between 1980 and 1985 alone; activists and social service providers often questioned such figures owing to the high rates of unauthorized migration and public authorities’ traditional undercounting of immigrant populations. Newcomers settled in the Mission and adjacent neighborhoods as their predecessors had done in decades past. They relied on existing social and institutional networks for support and interacted in varying degrees with established Latino residents and more recent Mexican immigrants. The latter continued to arrive steadily throughout the 1980s and 1990s, though their migration to the metropolis was not marked by the acceleration presented by the Central American case. Mexicans sought to escape economic instability, to obtain better employment than found in California agriculture, or to reconnect with kin. Seen from one perspective, these population flows merely reproduced Latinos’ heterogeneity along lines of national origin. But they diversified the local Latino population as well. The latest migrants represented a distinct generation, included a larger pool of undocumented immigrants, and found themselves having to compete for social services in a context of shrinking governmental commitment to the public welfare.

Latino San Franciscans’ quotidian existence in the 1980s and 1990s presented a study in contrasts. In 1990, approximately one-third of them lived in the Mission; the district remained “the heart,” as historian Cary Cordova has put it, of the community. Cultural life during these decades exhibited great effervescence and multilayeredness. Three Kings Day celebrations in January, street fairs, a Mardi Gras–style Carnaval every May since 1979, and an array of cultural productions at the Mission Cultural Center (founded in 1977) offered examples of festive and creative abundance. Leisure and nightlife for queer Latinos flourished as well. By the late 1980s, there were three venues near 16th and Mission, including Esta Noche and La India Bonita, catering to gay Latino men and sometimes frequented by lesbian and transgender Latinas. Most Latinos and other San Franciscans knew about this Mission zone for other reasons: drug dealing, crime, and homelessness. These societal ills were not specific to Latinos or the Mission, but they marked the district as unsavory and dangerous. So did the spike in gang activity; at least seven gangs with hundreds of young Latinos as members existed by 1995. Neighborhood service providers offered numerous explanations for this development, including peer pressure, a lack of social connectedness, poverty, and a desire “to defend [their] territorial autonomy” from outsiders.

Economic disparities beset Latinos across the city, and the specter of displacement continued to bedevil those living in the Mission. While Latino rates of labor force participation matched those of white residents, annual per capita incomes did not. Latinos earned roughly half of what whites made in 1980; the figure was decidedly less than half ten years later. The most economically vulnerable among them (e.g., residents with lower levels of education, recent immigrants) typically resided in the Mission. Notably, rising rents and real estate speculation persisted even as many San Franciscans cast the Mission as economically depressed and undesirable. “Gentrification is definitely here,” one nonprofit worker told El Tecolote in late 1986. Four years later, the San Francisco Chronicle noted how “Hong Kong investors, Asian grocers and bohemian artists” increasingly found the Mission attractive because of its “sunny weather, relatively affordable housing and busy shopping districts.”

Many Latinos did not regard their housing options, in the Mission or elsewhere, as inexpensive. One-half of all Latino households citywide paid “unaffordable rent” by 1990: they used more than 30 percent of their earnings to cover lodging. Low incomes, occupational segregation in service and clerical sectors, and high housing expenses placed many in an ongoing state of economic precarity.

Activism in response to employment and housing realities appears to have been subdued in the 1980s, though other issues consumed Latinos’ political energies. Commenting on housing pressures in the mid-1980s, one observer noted, “People are not organized to fight back.” Others stressed how American foreign policy, immigration, AIDS, and education pulled Latinos in multiple directions. A considerable number of them, including recent immigrants, mobilized against U.S. intervention in Central America and in support of the thousands fleeing war. Some participated in the Bay Area’s Sanctuary Movement, an organized effort of churches and community groups offering social services to Central American refugees, sheltering them from deportation, and advocating for fair and humane immigration policies. Humanity and death took on political urgency amid the AIDS crisis. Former members of the Gay Latino Alliance — which disbanded in 1983 — joined other gay Latinos in organizations such as Comunidad Respondiendo a AIDS/SIDA, founded in 1987, to devise communal responses to the epidemic, push local agencies to offer treatment and prevention services, and educate all Latinos about the disease. Educational reform and Latino representation on municipal bodies responsible for public education became the priorities for others.

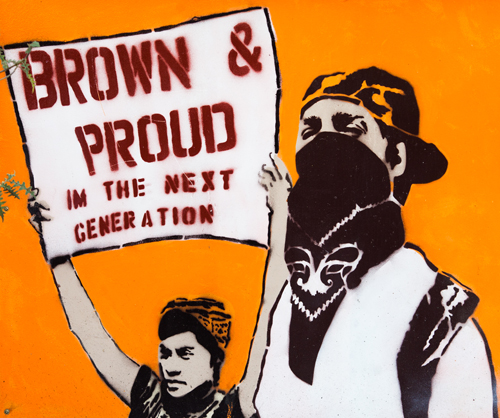

Immigrant rights, AIDS, and educational improvement remained critical concerns in the 1990s, while youth violence, work life, and gentrification garnered mounting attention. Throughout this decade, the Mission witnessed the unfolding of the Community Peace Initiative, a violence prevention effort funded by a private foundation. Missionites from all walks of life, including former gang members, took part in it. The initiative’s team coordinated community forums and peace rallies, conducted street outreach and mobilized young people around a host of interrelated issues (e.g., educational inequities, mass incarceration), and advocated for policies to treat violence as a public health issue. As a new generation of youth became politically engaged, Latino workers did as well, especially those in service-sector jobs. Growing numbers of housekeepers, food service workers, dishwashers, and janitors responded positively to the unionization drives carried out by the locals of the Hotel Employees and Restaurant Employees Union and the Service Employees International Union.

The development confirmed the potential of organizing a new generation of unskilled, immigrant workers and reviving the tradition of class-based solidarity. Mobilizing Missionites against displacement regained prominence as gentrification escalated in the late 1990s. By summer 2000, residents, artists, community groups, and neighborhood business owners came together under the Mission Anti-Displacement Coalition. MAC protested the housing crisis spawned by the dot-com boom and demanded a moratorium on the construction of new market-rate housing, live-work lofts, and digital office space. It proved clearly that direct action and policy advocacy could be channeled yet again to propose human-centered alternatives to the inequities bred by capitalism as the twenty-first century began.

Months after MAC’s emergence, San Franciscans once again elected their supervisors at the district level. The original experiment with district elections (1977–1980) had been short-lived; the city reverted to at-large elections for twenty years. Electoral results in December 2000, following many run-off contests, shifted the city’s “political power base decisively to the left.” Voters in the seven districts that sent left-leaning representatives to City Hall — including the new District 9 encompassing the Mission and Bernal Heights — celebrated the prospect of a new progressive agenda, one with initiatives “ranging from clamping down on dot-com development to easing up on homeless scofflaws.” It was an exhilarating period to be in the city — as a resident, an activist, or a scholar.

The early research phases for what would form part of this book began around that time. It was tempting to become absorbed in the activism of the early 2000s, but scholarly priorities directed me to the archives. I had returned to the city to understand what had transpired at least two generations earlier. San Francisco as research site originally drew me because of its motley Latino population. Historical scholarship on the alliances and tensions between Latino subgroups did not exist fifteen years ago, and it still remains rather slim. I also wanted to approach political action from multiple angles. The work on 1930s labor organizing and 1960s social movements fascinated me; yet most historians treating unionization rarely took their analyses beyond the early 1950s, and studies of social movements typically proceeded from the mid-1960s forward. At the same time, examinations of communal deliberations over gender and sexuality tended to emanate from literary and cultural studies fields. I set out to integrate these layers of political life and to historicize their connections and imbrication. Many years into the project, I realized that liberalism and latinidad were the threads holding my analysis together. Liberalism and latinidad, as I have argued, consistently framed and influenced Latinos’ aspirations and the trajectory of their political engagement.

I now understand that my initial trips to San Francisco took place as its residents confronted the transition and adjustments to a neoliberal order. Gentrification, homelessness, and decreased opportunities for social mobility, as many social scientists have shown, are largely products of neoliberalism. Historians explain that this “new” political ethos is rooted in classical liberalism; it promotes economic deregulation, a retreat from social welfare spending, rollbacks in state protection for workers, and a reverence for the free market. Many San Franciscans living at the turn of the twenty-first century sought to buck this current, and hoped the left-leaning supervisors who took office in 2001 would steer the city back on a progressive course.

Impressive changes certainly occurred in the new century, often in response to the demands and mobilizations of such groups as MAC and the San Francisco Living Wage Coalition. Between 2001 and 2008, the city initiated a program to offer health care to all uninsured residents, passed laws prohibiting the use of Styrofoam containers and plastic bags at grocery stores, mandated restaurants to display nutritional information on their menus, initiated an instant-runoff voting system, and widened supervisors’ authority over appointments and confirmations to city commissions. These developments reaffirmed a municipal commitment to social welfare, environmental regulation, and democratic reform. Wages and housing, of course, remained utmost priorities. In 2003, voters approved a citywide minimum wage ($8.50 an hour in 2004, $10.74 an hour by 2014) applicable to all employers, tied to inflation, and higher than state and federal levels. The policy came on the heels of an “inclusionary housing ordinance,” enacted in 2002, requiring private developers to offer 15 to 20 percent of new units at below market-rate prices. Residents in the Mission, Potrero Hill, and South of Market concurrently welcomed land use controls, temporary moratoriums on large office developments and live-work lofts, and public bodies’ increased efforts to engage them in community planning. Notably, as late as 2008, planning officials continued to express confidence in the city’s ability “to house diverse groups of people and address the citywide need for more affordable housing.”

Neither the housing crisis nor income inequality abated. By the mid-2010s, San Francisco could boast about its advantage in the digital economy, a boom in construction, its exceptionally low unemployment rate, and plans to increase the local minimum wage to $15 an hour effective July 2018. It had also become the nation’s costliest city for renters and one of the most economically unequal places in the country.20 Politicians, policy experts, and activists have proposed myriad solutions to navigate this reality. Some of these include building higher and relaxing land-use restrictions, halting condominium construction in the Mission and other in-demand neighborhoods, expanding rent control protections, and investing in a future middle class by turning low-wage service jobs into higher-paying jobs. Scholars and commentators, for their part, have pondered one question time and time again: “What’s the matter with San Francisco?” A popular account in an online magazine offered the simplest yet most telling response. “We’ve come so far on social issues, but gone backwards on the financial problems,” noted a Paste writer. Pointing out that much of San Francisco’s early twenty-first-century progressivism is actually neoliberalism, he underscored this observation: “We have progressive cultural values but conservative economic ones.”

Latinos experience the contemporary conundrum of liberalism on a daily basis. While the economic crisis is felt most acutely by those in low-wage service industries, Latinos and other San Franciscans who are administrative assistants, teachers, nonprofit workers, artists, and small business owners increasingly find the city unlivable.

Latinos and their allies have engaged in vigorous community mobilization to confront the present situation — as done in the past — and have met backlash against their efforts. Still, they have acquired a fair amount of political clout at the municipal level. In recent history, many Latinos backed and had the ear of socially and economically progressive legislators, including John Avalos and David Campos. Avalos represented the Excelsior and other southern neighborhoods; he ran a promising but unsuccessful mayoral campaign in 2011 and served as supervisor until 2016. Campos became the first gay Latino supervisor elected in the Mission; he served from 2008 to 2016. But political influence has not translated into economic security or guaranteed a future in San Francisco. This book stands as a reminder of past prospects, ambitions, and possibilities — when Latinos and other ordinary residents believed equality, opportunity, and social mobility were within their reach.

Eduardo Contreras is associate professor of history at Hunter College, City University of New York.