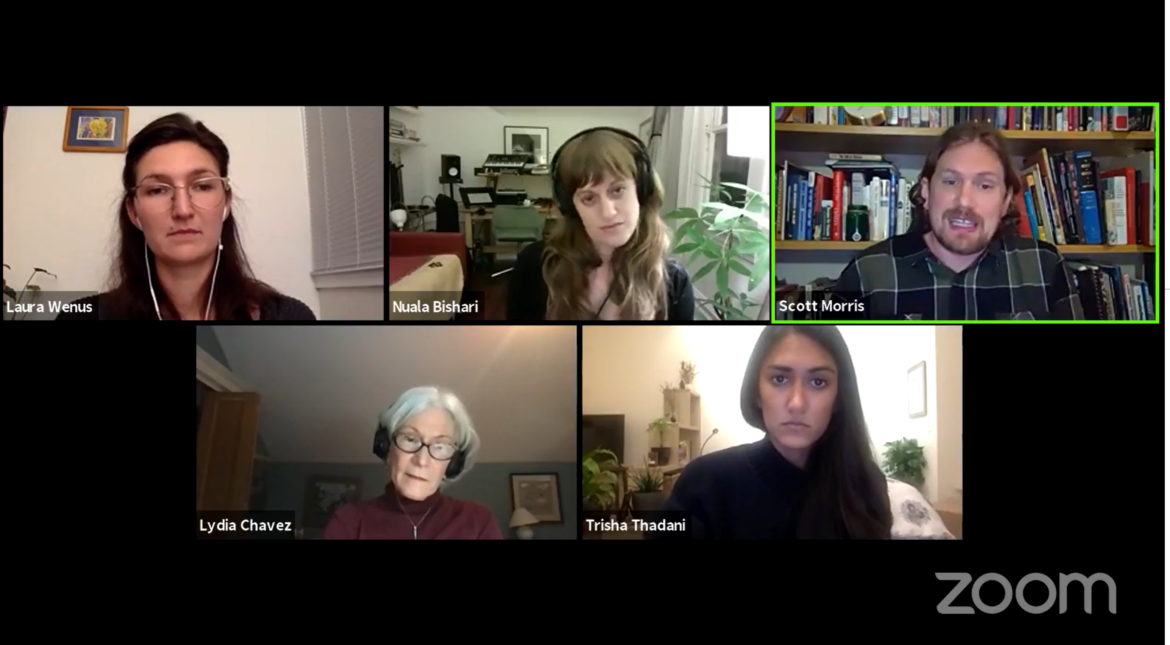

In late March 2020, the Society of Professional Journalists of Northern California, along with the First Amendment Coalition and other freedom of information groups, issued a rebuke of state agencies for indicating that they would stop responding to requests for records under the California Public Records Act until the COVID-19 crisis passes. The San Francisco Public Press hosted a roundtable discussion with local reporters about the difficulties they have experienced in accessing public information.

Locally, Mayor London Breed in spring 2020 suspended certain elements of the Sunshine Ordinance, an open records law in San Francisco. Journalists have also found it difficult to get answers to questions from various city departments during frequent virtual press conferences, where they must remain muted and submit their questions in specific formats.

“It’s a terrible setup. They just decide at some of these press conferences not to answer your questions,” said Lydia Chávez, executive editor at Mission Local, which has been focusing coverage of the pandemic on its disproportionate effects on the city’s Latino residents and pressing the Department of Public Health for testing location data. The constraints on when and how reporters may ask questions “just really puts journalists at incredible disadvantage,” she said.

Trisha Thadani, a city hall reporter with the San Francisco Chronicle who has covered outbreaks at nursing facilities and drug overdoses, echoed that concern and said that officials have several times simply not answered her questions. When coronavirus infections began rising at the city’s biggest skilled nursing facility, Laguna Honda Hospital, she said reporters and relatives of residents were barred from visiting the site and struggled to get information from the city about the conditions there.

“During that there were so many family members who had their older mom or dad in that facility and didn’t know what the hell was going on, and they were turning to us for answers,” Thadani said. “We’re the ones who are disseminating the information to the public when the government is falling short.”

In San Francisco, city departments also began funnelling media requests through the COVID-19 command center under the Department of Emergency Management.

“So right now, if you want to get a quote from the Department of Public Health, and often even the Department of Homelessness, you have to email DEM directly,” said Nuala Bishari, who writes for the San Francisco Public Press, In These Times and other media outlets. “The answers I get often do not come from the department that I’m trying to contact. Requests are very, very slow to actually land in my inbox. Sometimes it takes days and days, and they don’t arrive until well past my deadline. And the questions I ask are very rarely answered.”

Statewide, agencies have been blaming slow responses to records requests on the pandemic, said Scott Morris, who has been investigating utilities companies and their state regulator with the Bay City News Foundation and ProPublica

“A lot of people are using the pandemic as kind of excuse to delay or obstruct public records requests,” he said. “They say ‘well, because of COVID-19 we’re all working from home and our staffing is low.’”

In some cases, Morris said, agency representatives have even told him to simply put off his records request until the pandemic is over.

Withholding or slow-walking information that the public legally has access to erodes trust, the journalists said.

“When you look at city departments, especially something like the Department of Homelessness which has an enormous multi-million dollar budget, and we don’t understand the breakdown of where that budget is going, people start to lose trust in that department,” Bishari said.

Highlights from this discussion are also available as an episode of our radio program and podcast, “Civic.” Find the episode here. You can also hear “Civic” daily at 8 a.m. and 6 p.m. on 102.5 FM in San Francisco, and subscribe on Apple, Google, Spotify or Stitcher.