In 2019, the head of the government agency overseeing Treasure Island addressed the power outages residents had been living with for years. A crucial electrical upgrade was coming soon, and once it was complete, he “would be shocked if we had five outages the following year,” he said.

That work finished this July after repeated delays, but the outages persisted, threatening to spoil food, interrupt working or schooling from home and prevent the usage of crucial medical devices in one of the poorest neighborhoods in San Francisco. There were at least six outages in the subsequent three months.

The recent changes, however, “mark the most significant improvement that could be made to improve system performance and reliability,” said Robert Beck, director of the Treasure Island Development Authority, which owns the electrical system and directs its maintenance and upgrades. Though the new hardware will not eliminate outages entirely, it “will make them less frequent, more localized and shorter in duration,” he said.

This year’s outages each lasted between about two and 10 hours, city records show. Treasure Island has experienced 109 outages in the last five years, according to the San Francisco Public Utilities Commission.

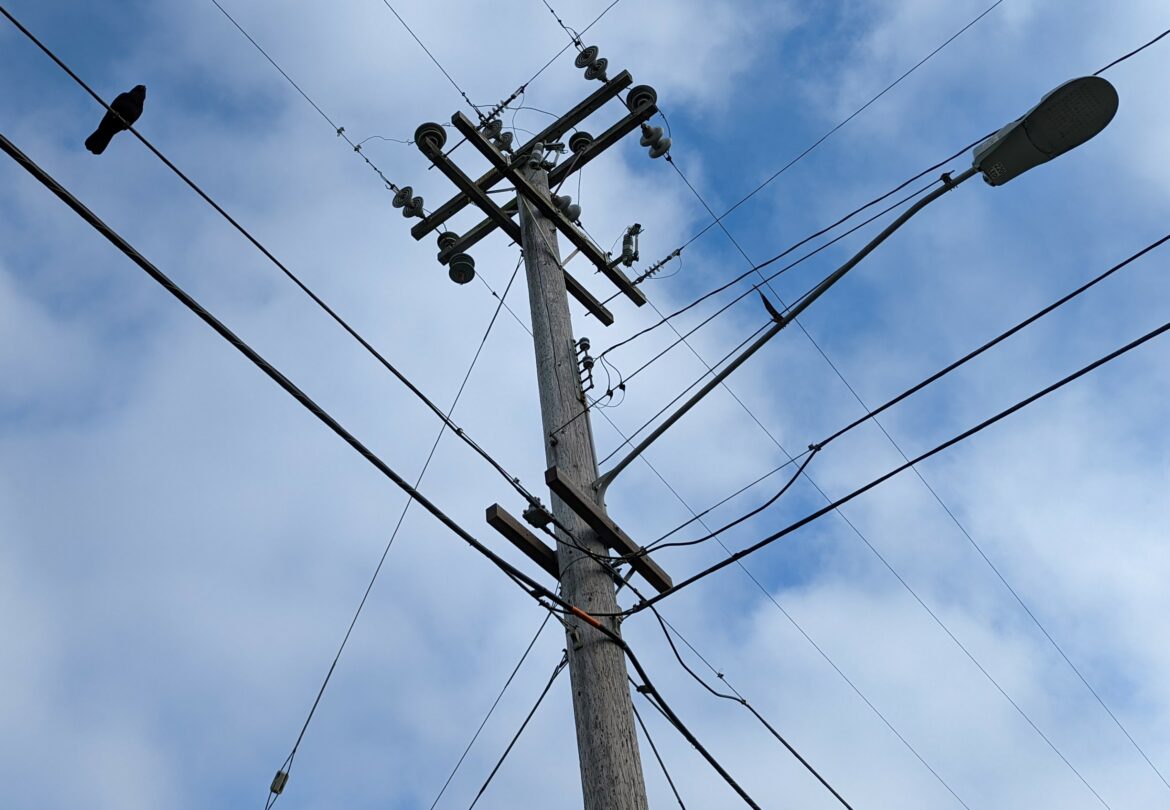

Old electrical equipment stretched thin

The island’s population is less white and affluent than San Francisco as a whole, with a median household income of about $54,375, compared with $112,449 citywide, census estimates show. A massive housing project, slated to finish by 2035, will expand the number of island residents from 3,000 to an estimated 20,000.

“The bulk of the existing distribution infrastructure is aged and vulnerable to outages,” said Beck, adding that two power failures in October were not the result of faulty equipment but of vandals apparently trying to steal copper conductors.

The housing project will entail the “elimination or replacement” of all electrical infrastructure, he said, moving it underground and making it less vulnerable to falling tree branches or bird collisions. “I would say unequivocally that when the system is entirely replaced, the island will not be experiencing outages at anything similar to the frequency that have been observed over the last several years.”

The authority is trying to find a balance between completing upgrades that make service more reliable and keeping rates low for island residents, who must cover the costs of improvements, Barbara Hale, assistant general manager for power at the city’s Public Utilities Commission, said in 2020. The commission carries out maintenance.

“You don’t want to replace it today when you know that two, three years from now you’re gonna have to replace it with all new equipment” for the larger housing project, Hale told the Public Press.

New equipment repeatedly delayed

A major upgrade to the island’s switchyard was originally slated for December 2020, but after multiple delays it was finished this summer. The new equipment is expected to help constrain the impact of certain types of outages, preventing them from affecting the entire island.

That has already borne out, Beck said: “We’ve had only one outage that effected all of Yerba Buena and Treasure Islands.”

Another major planned upgrade, to residential transformers that calibrate voltage to levels appropriate for residents’ daily use, was supposed to happen this October. It is also behind schedule, due to “procurement delivery delays,” though a handful of transformers were replaced this summer, Beck said in an email. “The SFPUC intends to award a contract shortly after the new year” to do the work, he said.

The upgrade could make a big difference, because transformers were responsible for two recent outages, said Barklee Sanders, a local watchdog. He has been tracking outages since shortly after moving to the island in 2018, and he publicizes them on social media and his website to alert his neighbors and hold the government accountable.

Sometimes his role in the community can feel overwhelming, he said, like when the power goes out late at night.

“I’m literally driving around and looking for the fault indicator,” Sanders said, referring to a piece of equipment that signals an outage’s origin so that workers can more quickly find it and get power back online. “I’m trying to tweet and update the website, responding on NextDoor, responding to other residents if they text me, reaching out to SF PUC about doing alerts about the outages.”

Sanders sits on advisory bodies for the Treasure Island Development Authority and the city’s Public Utility Commission. He said he’ll continue to push officials until outages decrease substantially. He would also like to see the government give residents backup batteries to provide power when the main source fails.

Adapting to unpredictability

For Antonio Mixon, the worst thing about the outages is that they cause food to spoil prematurely and they complicate cooking. Like many residents of the island, he has had to adapt.

Neal Wong / San Francisco Public Press

Antonio Mixon moved to Treasure Island from San Francisco’s Tenderloin neighborhood six years ago after gaining custody of his daughter. His family has learned to adapt to the power outages, with an indoor backup generator and candles and flashlights in every room.The outages often occur during inclement weather. “I filled the house up full of candles, flashlights, because it happens so often,” Mixon said.

If an outage interrupts his daily asthma treatments with his nebulizer, which requires 15 minutes of continuous power, he plugs into his car’s power. And six months ago, his wife bought an indoor generator as a backup power supply.

Other than that purchase, made possible when prices dropped during the pandemic, COVID-19 has “made everything worse,” he said.

The biggest blow has been to his daughter, who is 10 years old and attends school remotely. Each day she has about three hours of instruction by video conference, plus four or five additional hours of homework, all of which requires a steady internet connection. Power outages stop her in her tracks.

“We have to switch to the hotspots, and they don’t really run good,” Mixon said, adding that her school has been patient with her.

But he said he tries to keep the outages in perspective, and that his Treasure Island home is the best he’s ever had. He previously lived in a single-room occupancy hotel in San Francisco’s Tenderloin neighborhood. After a three-year effort he gained custody of his daughter and moved with her to subsidized housing on the island.

“Now I’m not stepping over people when I head out the door. There’s no human feces” on the pavement, Mixon said. “So, this is like heaven to me, even with the power outages.”