Summary

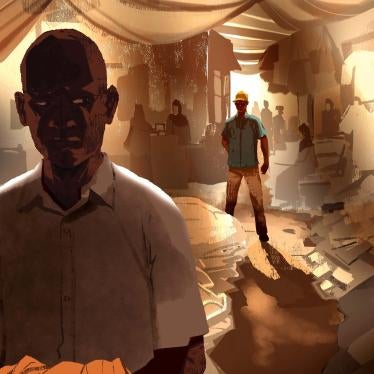

When a Rwandan journalist living in London, United Kingdom, sat down on a bench in a public park, in August 2022, the first thing he said, after nervous introductions, was: “My wife didn’t want me to come. We have to be careful.” His eyes darting around to check if anyone was eavesdropping, he explains how some of his relatives in Rwanda are under surveillance and have been marginalized because of his work. In London, he lives afraid and isolated, and has suffered from panic attacks and depression. He has a flak jacket and security cameras at home. “I’ve stopped attending any gatherings of Rwandans. I never invite Rwandans around to my house anymore. But now, I am attacked online,” he said.[1]

Rwanda’s President Paul Kagame and the ruling Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF) have often been credited with rebuilding a country left almost entirely destroyed after the 1994 genocide. As this report will show, however, the RPF, since it came to power in 1994, has also responded forcefully and often violently to criticism, deploying a range of measures to deal with real or suspected opponents, including extrajudicial killings, enforced disappearances, torture, political prosecutions, and unlawful detention, as well as threats, intimidation, harassment, and physical surveillance. Such measures are not limited to critics and opponents within the country.

The control, surveillance, and intimidation of Rwandan refugee and diaspora communities and others abroad can be attributed in part to the authorities’ desire to quash dissent and maintain control. By refusing to return to Rwanda and through their ability to criticize the Rwandan authorities from exile, refugees and asylum seekers also inherently challenge the image the authorities seek to project—one of a country from which people do not flee.

For this report, Human Rights Watch interviewed over 150 people in Australia, Belgium, Canada, France, Kenya, Mozambique, South Africa, Tanzania, the United Kingdom, the United States, Uganda, Zambia, and others related to them in Rwanda, to investigate the tactics used by the Rwandan government and its proxies to target Rwandans abroad.

The research found that the authorities have created an environment where many Rwandans abroad, even those living thousands of miles away from Rwanda, practice self-censorship, refrain from engaging in legitimate political activism, and live in fear of traveling, being attacked, or seeing their relatives in Rwanda targeted.

In this report, Human Rights Watch documented over a dozen cases of killings, kidnappings and attempted kidnappings, enforced disappearances, and physical attacks targeting Rwandans living abroad.

The report also finds that the Rwandan government has sought to use global police cooperation, including Interpol Red Notices, judicial mechanisms, and extradition requests to seek deportations of critics or dissidents back to Rwanda.

In many cases, interviewees’ relatives in Rwanda have themselves been targets of arbitrary detention, torture, suspected assassinations, harassment, and restrictions on movements to exert pressure on their family members abroad to stop their activism. This has effectively reduced many to silence. For example, one interviewee, who said his relative was tortured in a safe house in Rwanda for eight months because of his political activism in exile, told Human Rights Watch: “If you publish my name, they will kill him.” [2]

Some of the cases detailed in this report expose the extraordinary lengths to which the government of Rwanda is willing to go, and the means at its disposal, to attack its opponents. The combination of physical violence, surveillance, misuse of law enforcement—both domestic and international—, abuses against relatives in Rwanda, and the reputational damage done through online harassment points to clear efforts to isolate the individuals socially and diminish their financial and professional prospects in their host country. The cases also illustrate the relentless nature of the attacks: multiple tactics are often used simultaneously and, if one fails, others will be used until the person they are targeting is worn down.

As Rwanda has grown more prominent on the international stage, leading multilateral institutions, and becoming one of the continent’s largest peacekeeping troop contributors, the United Nations and international partners have consistently failed to recognize the scope and severity of the country’s dismal human rights record.

In Mozambique, for example, where the Rwandan troops’ deployment in 2021 has been credited with restoring peace and security in the northern Cabo Delgado province, this research also found that at least three Rwandans have been killed or disappeared in suspicious circumstances, and two others have survived kidnapping attempts, since May 2021. Several Rwandan refugees said they were threatened by embassy officials and being told they would die if they did not fall in line. One Rwandan refugee interviewed in Maputo said: “I am afraid all the time. I am afraid when I see a car pull up behind me. I’m afraid when someone [comes to my workplace]. I am ready to be killed at any time now. I’ve refused to go back to Rwanda, so they will kill me. There is nowhere to go. It’s not safe here, but it’s not safe anywhere.”[3]

The report focuses on abuses documented since 2017, the year when Kagame overwhelmingly won a third term with a reported 98.8 percent of the vote. A 2015 referendum entrenched his and the RPF’s rule by allowing President Kagame to run for a seven-year term and two additional five-year terms thereafter—and potentially stay in power until 2034. Since it took power, the RPF has implemented an ambitious development agenda and strove to change Rwanda’s image internationally and attract investments, tourism, and host high level events such as the first ever Basketball Africa League tournament in May 2021 and the Commonwealth Heads of Government Meeting in June 2022. However, these gains have not been matched with progress on civil and political rights – creating a “hostile international opinion” of the Rwandan government is a criminal offense that is regularly used to prosecute critics and journalists inside Rwanda and intimidate and silence critics.

The government of Rwanda actively seeks to discredit its critics abroad – particularly those who could undermine the RPF’s legitimacy. There are three main categories of people who are targeted outside of Rwanda’s borders: individuals who are influential—and often wealthy—figures in the Rwandan refugee community in their host country; political opponents or critics who use the relative safety of exile to criticize the government, including members of opposition and armed groups in exile or people suspected of having ties to these groups; and former members of both the RPF and the Rwandan Patriotic Army (RPA), now the Rwanda Defence Force (RDF), who have fled Rwanda.

This research found that Rwandan embassy officials or members of the Rwandan Community Abroad (RCA), a global network of diaspora associations tied to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and International Cooperation, have monitored and pressured Rwandan asylum seekers and refugees to return to Rwanda or stop their criticism of the government. For criticizing the government or the RPF, many Rwandans overseas were subjected to online attacks by websites and social media accounts that are alleged to have ties to Rwandan intelligence services and generally defend the government. The accusations disseminated on those sites range from supporting armed opposition groups to genocide denial. Rwandans living abroad – including Tutsi who fled Rwanda during or after the genocide – said that just the prospect of being targeted by such media deters them from speaking out. Several genocide survivors living in exile told Human Rights Watch that they had been attacked online for having criticized the RPF and had witnessed or were afraid to see their family members forced to denounce them on pro-government YouTube channels.

Human Rights Watch documented five cases of killings, three kidnappings and attempted kidnappings, and at least six cases of physical assaults and beatings – some of which appeared to be attempted killings – of Rwandan permanent residents, refugees, and asylum seekers in Kenya, Mozambique, South Africa, Tanzania, and Uganda. In some cases, the perpetrators spoke Kinyarwanda, Rwanda’s national language, or were suspected of working for the Rwandan government. Some of the victims were told they would be handed over to Rwanda or were accused of working against the Rwandan government.

As critics or opponents, perceived or real, of the government, the victims all share a certain profile; prior to these attacks many had been threatened by individuals who were part of, or close to, the Rwandan government. The context of broader persecution of government critics inside Rwanda provides credibility to the allegation that these attacks were politically motivated. It also raises serious and plausible concerns about the possibility of official state tolerance, acquiescence, or even collusion in these attacks.

These violent abuses are alarmingly frequent, particularly in African countries and in countries where the Rwandan government has an active presence, including a military presence, embassies, diaspora associations, or economic partnerships. In almost all cases, host government investigations have stalled or failed to result in any arrests or prosecutions. In some cases, the host country’s authorities appeared to have colluded with Rwanda—or at the very least to have turned a blind eye. This has left many Rwandans feeling unprotected; unless action is taken, these abuses are likely to worsen because of Rwanda’s expanding influence across the African continent.

This report also documented five cases where Rwandan authorities have sought to have Rwandans arrested and renditioned to Rwanda, particularly in East Africa, often through apparently unofficial requests made to local law enforcement. In some cases, law enforcement officials in the host country refused to carry out the deportations but failed to ensure adequate protection of the victim. In others, the detention and possible or confirmed rendition amounted to an enforced disappearance. Human Rights Watch documented three cases of Rwandans in Kenya and Uganda who narrowly escaped deportation to Rwanda after being arbitrarily detained by law enforcement officials. In at least one case, Kenyan authorities simply told the asylum seeker to leave the country for his protection. These tactics have created a deep-seated fear of traveling for many Rwandans living abroad. Many Rwandans interviewed in Europe and North America said they no longer travelled to Africa because they felt it was too dangerous.

When seeking to target dissidents, the Rwandan authorities showed little regard for the independence of the judiciary or the duties of protection of law enforcement in host countries. The Rwandan government misused Interpol Red Notices in two cases, and, in one of them, obtained the extradition of a Rwandan asylum seeker living in the US based on genocide accusations which were later overturned in a Rwandan court. He remains in prison in Rwanda, convicted of genocide denial.

Many interviewees who have chosen to continue their public criticism in exile have had to cut communications with their relatives in Rwanda. Several interviewees said their family members in Rwanda are under surveillance or have been denied passports, which prevents them from leaving Rwanda.

Two Rwandans living abroad—now naturalized citizens in France and the UK, respectively—were detained in Rwanda after traveling there for personal reasons. They were targeted apparently in retaliation for their relatives’ political activism in France and the UK and subjected to Rwanda’s arbitrary and abusive judicial practices. Foreign affairs officials from those countries were aware of both cases and intervened to secure their release. The Rwandan authorities failed to respect due process in these cases, and the lack of credibility of the charges against both individuals highlights the risk of abuse and politicized prosecutions, even for refugees and other Rwandans who have acquired the citizenship of another country.

The targeting of relatives is a particularly vicious form of control which may explain why so much of Rwanda’s prolific extraterritorial repression—which goes far beyond high-profile cases of assassinations, assassination attempts, and disappearances—has not been visible.

In targeting actual or perceived dissidents abroad and their relatives, Rwandan authorities have violated an array of rights including life, privacy, freedom of expression and association, physical safety, freedom of movement, freedom from torture, and the right to a fair trial.

On a global scale, extraterritorial abuses by governments and other actors against their own people have a particularly chilling effect, both at home and abroad. It is precisely the reason why some governments resort to these tactics: to send the message that nowhere is safe for those who criticize them.

Many of the host countries cited in the report—such as the UK and the US—have close partnerships with, and are major donors to, Rwanda. These and other governments should use their close ties to pressure the Rwandan government to improve its human rights record both domestically and abroad; yet they rarely—if ever—raise human rights concerns publicly in their bilateral or multilateral engagement. The UN refugee agency, UNHCR, and host countries’ authorities should fully investigate reports of abuse and ensure adequate protection of at-risk Rwandan asylum seekers, refugees, permanent residents, and naturalized citizens. Countries in East and Southern Africa, where Rwandans are most prone to state sponsored attacks and renditions, should investigate and prosecute officials who have facilitated Rwanda’s extraterritorial abuse.

The failure of the UN and international community to recognize the severity and scope of the Rwandan government’s human rights violations both domestically and abroad, as well as the ruling party’s growing hostility toward those it perceives as challenging its nearly 30 years in power, have left many Rwandans with nowhere to turn. Holding Rwanda accountable for its dismal domestic human rights record is now a necessity to tackle the government’s extraterritorial repression.

Terminology and Acronyms

Diaspora: While there is no one agreed-upon definition of “diaspora,” the term can encompass people who have left their home country voluntarily or involuntarily and are living abroad, including asylum seekers, refugees, and other immigrants, sometimes referred to as expatriates, as well as their descendants. The International Organization for Migration (IOM) defines diasporas as “migrants or descendants of migrants, whose identity and sense of belonging ... have been shaped by their migration experience and background.” Some Rwandans living abroad interviewed for this report, when using the term “diaspora” or when talking about “joining the diaspora,” were referring to diaspora associations and the Rwandan Community Abroad (defined below).

Extraterritorial repression (also known as transnational repression): A systematic effort by a country’s authorities or their proxies to prevent political dissent beyond the country’s borders by employing a range of tactics to silence and control refugees, asylum seekers, and other members of the diaspora.

Interahamwe (“Those Who Stand Together” or “Those Who Attack Together” in Kinyarwanda): The militia attached to the ruling party, the National Revolutionary Movement for Development, under President Juvénal Habyarimana. In the lead up to and during the genocide, the Interahamwe carried out killings of Tutsi and moderate Hutu. From the start of the genocide, political leaders put the militia at the disposal of the military.

Interpol Red Notice: An alert by the International Criminal Police Organization (Interpol), issued at the request of a member state seeking the arrest and extradition of a wanted person.

RCA: Rwandan Community Abroad, a group of associations tied to Rwandan diplomatic missions and the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and International Cooperation, charged with mobilizing and monitoring the Rwandan community abroad, providing services on behalf of the government, and organizing gatherings such as “Rwanda Day.”

RNC: Rwanda National Congress, an opposition group in exile created by former officials of the RPF (Rwandan Patriotic Front).

RDF: Rwanda Defence Force, formerly the RPA (Rwandan Patriotic Army).

RPF: Rwandan Patriotic Front, a largely Tutsi politico-military movement and currently the ruling party in Rwanda. Before it took power in 1994, the RPF was a rebel group consisting mainly of Rwandan Tutsi refugees in Uganda.

Defining Extraterritorial Repression

Extraterritorial, or transnational, repression is the phenomenon of governments engaging in activities that involve or lead to the violation of human rights of specific targets outside of their territorial jurisdiction. Human Rights Watch, in this report, and drawing on decades of documenting individual cases of extraterritorial repression globally, is particularly concerned with systematic efforts by a country’s authorities or their proxies to prevent political dissent beyond their territorial borders by employing a range of tactics to silence and control refugees, asylum seekers, and other members of the diaspora. The tactics include physical abuse, online harassment, exploiting technological vulnerabilities, the misuse of international and domestic law enforcement, and the manipulation of family ties to threaten, pressure, and punish real or perceived dissidents living abroad. Although awareness of extraterritorial repression has grown in recent years, many of the tactics used by governments to silence citizens living abroad, as well as the level of coordination that is exercised to monitor and control their activities, have been underreported.

Freedom House, which has done extensive work on extraterritorial repression, defines it as “governments reaching across borders to silence dissent among diasporas and exiles, including through assassinations, illegal deportations, abductions, digital threats, Interpol abuse, and family intimidation.”[4] The US Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), which has made transnational repression a priority, found that it can take the following forms: “stalking, harassment, hacking, assaults, attempted kidnapping, forcing or coercing the victim to return to the home country, threatening or detaining family members in the home country, freezing financial assets, [and] online disinformation campaigns.”[5]

Human Rights Watch, in this report, has documented killings, kidnappings and attempted kidnappings, enforced disappearances, and physical attacks targeting Rwandans living abroad. In addition, Human Rights Watch has found that the government of Rwanda has attempted to use global legal assistance mechanisms by issuing arbitrary Interpol Red Notices and extradition requests and getting involved in the prosecution of a dissident in a foreign court. Interviewees also described how Rwandan authorities have sought to silence them by perpetrating serious human rights violations against their relatives in Rwanda and abroad, including enforced disappearances, arbitrary detention, alleged ill treatment or torture, suspected killings, harassment, restrictions on movements, and alleged land seizures.

In most cases, no definitive domestic or international investigations have been conducted to establish responsibilities and enforce accountability. Such impunity risks emboldening other governments to go after prominent journalists, human rights advocates, or dissidents, wherever they may be seeking protection.

Abuses against those who have fled the territory of the government which they have criticized have a particularly chilling effect, both at home and abroad. It is precisely the reason why some governments resort to these tactics: to send the message that nowhere is safe for those who criticize them

Methodology

This report is based on in-person research conducted between October 2021 and December 2022 in Belgium, France, Kenya, Mozambique, South Africa, Tanzania, Uganda, the UK, and the US. Additional phone interviews were conducted with victims and witnesses in Australia, Belgium, Canada, the Democratic Republic of Congo, the Republic of Congo, France, Kenya, Mozambique, Rwanda, South Africa, Tanzania, Uganda, the UK, the US, and Zambia.

Human Rights Watch interviewed over 150 people, including victims of abuse, their relatives and lawyers, witnesses, independent journalists, representatives of international nongovernmental organizations and UN agencies, and government officials. Extensive corroboration was carried out to ascertain the credibility of sources and to obtain documentation supporting their claims, including multiple interviews with relatives, independent witnesses, and reviews of online harassment and other supporting documentation.

The victims include asylum seekers, refugees, refugees who have obtained permanent residency or citizenship in their host countries, and other members of the diaspora, including non-refugee residents or naturalized citizens.

Most of the interviewees feared for their security or the security of their family members and only spoke on condition that their names and other identifying information be withheld. Details about their cases or the individuals involved, including the location of the interviews, have also been withheld when requested or when Human Rights Watch believed that publishing the information would put interviewees or their family members at risk.

Interviews with victims, their relatives, or witnesses were conducted in confidential settings or through secure means of communication. Human Rights Watch informed all participants of the purpose of the interview, its voluntary nature, and how the information would be used. Each participant orally consented to be interviewed and were informed that they could refuse to participate or end the interview at any time.

Human Rights Watch did not make any financial payments or offer other incentives to interviewees. Care was taken with victims of trauma to minimize the risk that recounting their experiences could further traumatize them.

Whenever possible, Human Rights Watch also reviewed case files, medical records of victims, and death certificates. In addition, Human Rights Watch transcribed and translated all of the YouTube videos used as evidence of online harassment in this report.

Human Rights Watch sent multiple information requests and invitations to comment to a number of government authorities, private companies, institutions, and private individuals for this report. These include:

- Governments:

- Australian Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade; Department of Home Affairs; the New South Wales Police; and the Australian Federal Police.

- Belgian Foreign Affairs, Foreign Trade and Development Cooperation Federal Public Service: Africa South of the Sahara Department, Human Rights Department, and Special Envoy for Asylum and Migration.

- British Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office; and Home Office.

- French Ministry for Europe and Foreign Affairs; and Ministry of Interior.

- Kenyan Ministry of Interior and National Administration; and the Refugee Affairs Secretariat.

- Mozambican Ministry of Justice, Constitutional and Religious Affairs; and Ministry of Interior.

- Rwandan Ministry of Justice.

- South African Ministry of Home Affairs; Ministry of Justice and Correctional Services; and Minister of Police.

- Tanzanian Ministry of Constitutional and Legal Affairs; Ministry of Home Affairs; and Tanzania Communications Regulatory Authority.

- Ugandan Ministry of Internal Affairs; and the Uganda Police Force.

- US Department of Homeland Security; Department of Justice; and Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI).

- Akin Gump Strauss Hauer & Feld LLP

- Chelgate

- Day Pitney LLP

- GainJet Aviation S.A.

- Millicom International Cellular S.A.

- Interpol

- Dr. Michelle Martin

- Myriad International Marketing LLC

- Racepoint Global

- Tigo Tanzania

- United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees’ Division on International Protection, Regional Office for East, Horn of Africa & Great Lakes, and Regional Office for Southern Africa

- W2 Group, Inc.

Background

The Genocide and its Aftermath

Since Rwanda’s independence in 1962, a number of factors, including cycles of ethnic-based violence, political instability, and human rights violations have pushed many Rwandans to flee. The Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF), a politico-military movement made up largely of Tutsi, invaded Rwanda in 1990 with the declared aim of ensuring the right to return of refugees, many of whom had been living in exile for a generation, and of ending the rule of President Juvénal Habyarimana. Like most government officials at the time, Habyarimana was from the Hutu majority ethnic group. After nearly three years of alternating combat and negotiations, the RPF and the Rwandan government signed a peace treaty in August 1993 but an agreed-upon transitional government was never put in place.[6] By 1993, there were an estimated 600,000 Rwandans living in neighboring countries.[7]

In April 1994, an airplane carrying Habyarimana was shot down, triggering ethnic killings across Rwanda on an unprecedented scale. Orchestrated by Hutu political and military extremists, the genocide that followed claimed more than half a million lives and destroyed approximately three quarters of Rwanda’s Tutsi population in just three months.[8] Many Hutu who attempted to hide or defend Tutsi and those who opposed the genocide were also targeted and killed. In July 1994, the RPF took control of Rwanda and drove the government and its defeated army out of the country. During this period in Rwanda—as later in the Democratic Republic of Congo, then called Zaïre—RPF soldiers committed serious violations of international humanitarian law, including massacres and summary executions of civilians.

Hundreds of thousands of Rwandans, most of them Hutu, who fled from the advancing RPF troops, settled in huge refugee camps in Congo, while others went to Tanzania and Burundi. The refugees were accompanied by people who had participated in the genocide, including members of the former government, army, and Interahamwe—a militia attached to the ruling party—who established control over some of the refugee camps. Little was done by the then-Zaïrian government or UN agencies to demilitarize the camps which Hutu extremists used as bases for preparing attacks on Rwanda and pursuing anti-Tutsi propaganda campaigns.[9]

Arguing the need to stop this threat, the Rwandan government twice invaded Congo in 1996 and 1998, occupying a resource-rich territory some 10 times the size of Rwanda. In November 1996, the new Rwandan army formed by the RPF, the Rwandan Patriotic Army (RPA), invaded Congo and, together with a hastily constituted Congolese rebel group it supported, the Alliance of Democratic Forces for the Liberation of Congo-Zaïre (Alliance des forces démocratiques pour la libération du Congo-Zaïre, AFDL) which was also backed by Uganda, set out to destroy the refugee camps. The rebels and their backers went on to overthrow the country’s president, Mobutu Sese Seko, who had backed the Rwandan Hutu extremists, a few months later.[10]

Thousands of refugees were killed in the attacks on the camps, which forced the return to Rwanda of many of the surviving Hutu refugees. Many were arrested on their return on accusations of genocide; others were among thousands killed by the RPA in counterinsurgency operations in northwestern Rwanda in the late 1990s.[11] Those refugees who did not return to Rwanda, including large numbers who had not been involved in the genocide, fled deep into the forests of Congo, where Rwandan and AFDL troops massacred tens of thousands of them.[12] Many also fled south toward Malawi, Mozambique, South Africa, Zambia, and Zimbabwe.[13]

Today, Congo remains largely unstable, and violence continues in its eastern region, where more than 100 armed groups operate, including an armed group formed by some members of the former Rwandan army, Interahamwe militia, and other individuals suspected of having participated in the genocide. After changing its name a number of times, this group became known as the Democratic Forces for the Liberation of Rwanda (FDLR). Most current FDLR members are too young to have participated in the genocide in Rwanda, so it is incorrect to imply that all those fighting for the FDLR participated in the genocide. However, the FDLR leadership still includes some individuals believed to have participated in the genocide.

The FDLR have become weakened militarily in recent years and are only able to conduct rare attacks into Rwanda. In 2012, and again in 2022, Rwandan authorities sent troops across the border into eastern Congo, in support of the M23 armed group, which claims to protect Congolese Tutsi and to fight the FDLR.[14] On both occasions, the Rwandan government condemned the threat that the FDLR could pose to Rwanda and accused the Congolese government of supporting them.

The M23 was originally made up of soldiers who participated in a mutiny from the Congolese national army in April and May 2012. These soldiers were previously members of the National Congress for the Defense of the People (Congrès national pour la défense du peuple, CNDP), a rebel group which was also backed by Rwanda. Human Rights Watch documented the widespread abuses that amounted to war crimes perpetrated by M23 forces that, with support from Rwanda, took over large parts of North Kivu province in 2012.[15] In late 2021, the M23 began rebuilding its ranks. Since May 2022, Rwanda-backed M23 forces have once again overrun UN-backed Congolese forces in eastern Congo, committing war crimes in the process.[16]

The Rwanda National Congress

In 2010, Gen. Kayumba Nyamwasa, a senior Rwandan military official who had held several top positions in the RPF and in the security forces, including army chief of staff, fled Rwanda to South Africa, where he became an outspoken critic of President Paul Kagame. Together with other former senior RPF officials, he founded the Rwanda National Congress (RNC), an opposition group in exile.

The Rwandan government has repeatedly accused the RNC of collaborating with the FDLR, and of supporting and conducting terrorist activities in Rwanda.[17] The UN Group of Experts on Congo also pointed to collaboration between the two groups in 2019,[18] although the RNC has denied it.[19]

In January 2011, Nyamwasa and three RNC cofounders—all former senior government and army officials—were tried in absentia by a military court in Kigali and found guilty of endangering state security, destabilizing public order, “divisionism,” defamation, and forming a criminal enterprise. Nyamwasa and Théogène Rudasingwa, the former secretary general of the RPF, were each sentenced to 24 years in prison, and Patrick Karegeya, the former head of external intelligence, and Gerald Gahima, the former prosecutor general, to 20 years each.[20]

In May 2012, the government invalidated the Rwandan passports of Nyamwasa and six other members of the RNC without notification or possibility of appeal. In 2019, the African Court on Human and Peoples’ Rights[21] concluded that this constituted a violation of the right to freedom of movement[22] and the right to participate in political life.[23]

Several RNC members or suspected members have been attacked, in Rwanda and abroad.[24] Among the most prominent are Nyamwasa himself, who narrowly escaped an assassination attempt in South Africa in June 2010, and Karegeya, who was found strangled in a hotel room in Johannesburg, South Africa, in January 2014. Other RNC members, or people suspected of links with the RNC, have been arrested, prosecuted, and convicted in Rwanda.[25]

Many Rwandan officials, including Kagame himself, grew up in Uganda and fought alongside Ugandan President Yoweri Museveni and his National Resistance Army/Movement (NRA/M), which took the reins of power in Uganda in 1986, after a five-year-long guerrilla war. Since the creation of the RNC, relations between the two governments have grown increasingly volatile as Rwanda regularly accuses Uganda of supporting and sheltering the RNC.

Human rights defenders in Uganda have documented dozens of cases of suspicious killings, disappearances, and deportations to Rwanda in the last decade, alleging Rwandan collaboration with Ugandan military intelligence agents and security forces.[26] One such case was that of Joel Mutabazi, a former presidential bodyguard, who was forcibly returned from Uganda to Rwanda in October 2013.[27] In October 2014, a military court in Rwanda found him guilty of terrorism, forming an armed group, and other offenses linked to alleged collaboration with the RNC and the FDLR, and sentenced him to life in prison.

Relations between the two countries soured in 2019. Rwanda accused Uganda of supporting the RNC and harassing Rwandans, while Uganda accused Rwanda of conducting illegal espionage. The former Ugandan Inspector General of Police, Kale Kayihura, was arrested in June 2018, brought before a military court and charged with failing to protect war materials, failing to supervise police officers, and abetting the kidnapping and forced repatriation of Rwandan refugees.[28] The land border between the two countries was closed for three years.[29] After some back and forth between officials from both countries, including Museveni’s son Lt. Gen. Muhoozi Kainerugaba’s visit to Kigali, the border was reopened in January 2022.[30]

Justice and Free Speech

Since the genocide, Rwanda has made great strides in rebuilding the country’s institutions and infrastructure, which were almost completely destroyed in 1994. The Rwandan government has developed the economy, delivered public services, and made progress in reducing poverty.[31] It has set itself ambitious priorities for the country’s development, which it has pursued with determination over the last two decades.[32]

But the genocide continues to weigh heavily on the country. Delivering justice for mass atrocities was a daunting challenge, and the scale and complexity of the genocide would have overwhelmed even the best equipped judicial system.

The UN Security Council established the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (ICTR) in 1994 in response to the genocide. The tribunal indicted 93 people, convicted and sentenced 62, and acquitted 14. It made significant contributions to establishing the truth about the planning of the genocide and providing justice to victims. However, the ICTR only handled a small number of cases and was unwilling to prosecute war crimes and crimes against humanity committed by the RPF.[33] The tribunal formally closed on December 31, 2015.[34] Remaining cases were to be tried before the International Residual Mechanism for Criminal Tribunals (IRMCT) or transferred to Rwanda.[35] The IRMCT was established to handle the outstanding functions of the ICTR and the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY) once those tribunals closed. The mechanism has branches in Arusha, Tanzania, and The Hague, the Netherlands.

The Rwandan justice system also tried many genocide suspects, both in conventional domestic courts and in local, community-based gacaca courts. The standards of these trials varied enormously, and political interference as well as pressure resulted in some unfair trials. Other cases have shown greater respect for due process. The gacaca trials ended in 2012.[36]

As it wound down its work between 2011 and 2015, the ICTR transferred several genocide cases to Rwandan courts. To provide for the transfer of those cases, as well as extraditions of genocide suspects from other countries, the Rwandan government undertook reforms to the justice system aimed at meeting international fair trial standards. But the technical and formal improvements in laws and administrative structure were not matched by gains in judicial independence and respect for the right to a fair trial.

“Genocide Ideology” and “Divisionism”

After the genocide, a transitional government consisting of representatives of the RPF and the other political parties that signed the 1993 Arusha Accords ruled the country. Elections were held in late 2003 and Paul Kagame, formerly vice president and minister of defense, was elected president. In the lead-up to the election, Kagame threatened political opponents and forced some into exile, promising to “wound” any who failed to understand and heed his message against “divisionism.”[37]

From the outset, the RPF did not tolerate any criticism, dealing ruthlessly with real or suspected opponents through extrajudicial killings, enforced disappearances, torture, and unlawful detention, as well as threats, intimidation, harassment, and intense physical surveillance.[38]

In the decades that followed the genocide, as some Rwandan officials were reforming technical and formal aspects of judicial administration, others were carrying forward a far-reaching campaign against what in Rwanda is known as “divisionism” and “genocide ideology.” This campaign has had a broad impact on many aspects of Rwandan life, particularly in the domains of judicial independence and the rights of the accused to present witnesses, to be presumed innocent, and to have equal access to justice.[39]

Since 1994, Rwanda has passed several laws that were intended to prevent and punish hate speech of the kind that led to the genocide, but which have restricted free speech and imposed strict limits on how people can talk about the genocide and other events around 1994 and the subsequent 1996 Rwandan invasion of Zaïre. Accusations and charges of genocide ideology have been used routinely to silence prominent critics of the government.[40]

Rwandan law defines genocide ideology as a public act that manifests an ideology that supports or advocates for destroying—in whole or in part—a national, ethnic, racial, or religious group.[41] A 2013 revised version of the law defined the offense more precisely and required evidence of the intent behind the crime, reducing the scope for abusive prosecutions.[42] But the revision of the law adopted in 2018 removed language requiring evidence of a “deliberate” act and added provisions that could be used to criminalize free speech. For example, under the 2018 revised law, “Affirm[ing] that there was double genocide,” which is often interpreted as referring to crimes committed by the RPF, and “providing wrong statistics about the victims of the Genocide” are punishable by up to seven years in prison.[43] Although these statements may be offensive to genocide survivors, and contrary to research findings by Human Rights Watch and other independent organizations, the law opens the way to misuse and for the government to effectively criminalize free speech.

The RPF contends that, although some RPA soldiers may have killed civilians when it invaded Rwanda, these crimes were the unfortunate result of wartime or were occasional acts of revenge and have been punished.[44] However, representatives of four UN agencies as well as international and Rwandan nongovernmental organizations have documented war crimes committed by the RPA.[45]

In the text of Rwandan laws about “divisionism” and “genocide ideology,” and in public presentations, Rwandan officials often say they seek to eliminate these ideas to prevent future violence.[46] While this goal is certainly legitimate, the policies pursued by Rwandan authorities over the decades have shown that they have other reasons for seeking to eliminate certain views they deem inappropriate. Promoting conformity on certain important questions has been central to RPF practice from its early days, even before the genocide.[47]

Refugee Returns

Over 3.5 million Rwandans became refugees in the wake of the 1994 genocide and armed clashes in northwestern Rwanda in 1997 and 1998, according to the UN refugee agency, UNHCR.[48] According to UNHCR, by 2013, all but an estimated 100,000 had returned to Rwanda, “owing to lasting peace and stability in their country.”[49]

Many who fled the genocide were recognized in neighboring countries as refugees on a “prima facie” basis (as a group) due to the mass influx.[50] Many qualified as refugees under the persecution-based definition in the 1951 Refugee Convention and the 1969 African Refugee Convention,[51] or under the latter’s expanded refugee definition, which also encompasses those fleeing “events seriously disturbing public order.”[52]

In the decade that followed the genocide, even while some refugee displacement continued, hundreds of thousands of refugees returned to Rwanda.[53] After the conflict in eastern Zaïre escalated in October 1996, more than 600,000 Rwandans returned to Rwanda. And in December 1996, 500,000 Rwandans returned home from Tanzania after a controversial repatriation campaign.[54]

Rwandan authorities organized “solidarity camps,” known today as ingando, to convey political lessons to refugees who had followed the genocidal government into exile and who returned in large numbers in late 1996 and 1997. The camps were meant to promote ideas of nationalism, to erase the ethnically charged lessons taught by the previous government, and to spur loyalty to the RPF. Salaried employees who wished to return to public or private employment and young people who wanted to return to education ordinarily had first to complete a training session at an ingando camp.[55]

Many Rwandans refused to return for fear of persecution, citing continuing disappearances, extrajudicial executions, arbitrary arrest and detention, unfair trials, as well as the illegal confiscation and occupation of property by government officials and security forces.[56]

Yet the Rwandan government continued to seek the return of Rwandan refugees from neighboring countries and exerted pressure on governments in the region to cooperate in repatriations. Uganda, Burundi, and Tanzania all forcibly returned refugees to Rwanda without considering their individual cases on several occasions over the last few decades.[57]

Rwanda pressured UNHCR and states hosting Rwandan refugees to invoke (by December 31, 2011) what is known as the “cessation clause” in both the UN and African refugee conventions.[58] Under the cessation clause, UNHCR and host countries can declare that a given group of refugees no longer needs international protection because they can avail themselves of the protection of their home government—allowing them to withdraw refugee status for the group—if they believe the circumstances leading to the original refugee displacement have ceased to exist.[59]

In June 2013, UNHCR recommended the implementation of the cessation clause for Rwandan refugees who left the country between 1959 and 1998.[60] Doing so had the effect of reinforcing the perception that Rwanda is stable and safe, and many Rwandans interviewed for this report thought it made it harder for Rwandan asylum seekers to obtain refugee status.

Several countries that followed UNHCR’s recommendation and implemented the cessation clause encountered long delays in repatriations.[61] Many other countries did not implement the clause but have established tripartite agreements with Rwanda and UNHCR to facilitate “voluntary” returns.[62]

The invocation of the cessation clause reinforced the flawed assumption that positive developments in Rwanda ensured that refugees could return safely. While the mass violence of the genocide itself—“events seriously disturbing public order”—had ended, repression of political opinion and association in the aftermath of the genocide continued in the ensuing years, raising significant doubt that the key criteria of the cessation clause—that the circumstances that caused people to be recognized as refugees had “ceased to exist” to the extent that their home country would now protect them—had been met. [63]

The failure of the UN and many governments to recognize the severity and scope of the RPF-dominated government’s human rights violations, as well as its hostility toward those it perceives as challenging its nearly 30 years in power, has left many Rwandans with nowhere to turn. The threat of losing refugee status or of forcible return to Rwanda left tens of thousands of Rwandans living in countries that invoked the clause in a state of uncertainty about their future and immediate safety. Refugees interviewed for this report said the cessation clause had also caused a serious breakdown in trust between refugee communities and UNHCR, because the agency had complied with the Rwandan government’s request.[64] Displaced Rwandans who are stripped of refugee status and do not return home risk becoming undocumented in their host country, which can impede their access to numerous basic services in violation of their rights.

Human Rights Watch wrote to UNHCR to seek information and requested its view on its invocation of the cessation clause and its impact on the protection of Rwandan refugees. UNHCR responded in a letter dated August 22, 2023, and by email in September 2023, noting that it had assisted with the return of 65,000 Rwandans between 2012 and 2022, including 63,500 from Congo.

UNHCR stated, “Presently, there are 28,000 Rwandan refugees registered in the East, Horn and Great Lakes region (Burundi, Djibouti, Ethiopia, Eritrea, Kenya, Somalia, South Sudan, Sudan, Tanzania, and Uganda), and 218,000 Rwandans refugees in Southern Africa Region (Angola, Botswana, DR Congo, Eswatini, Malawi, Mozambique, Namibia, Republic of Congo, South Africa, Zambia, Zimbabwe), amongst which 208,000 estimated in the DR Congo by the Congolese government and 10,000 registered in the other countries of the Southern Africa region. If we exclude the figure for Congo, which is an estimate, the number of Rwandan refugees in the two regions is declining compared to 1998.” UNHCR said that the number of Rwandan refugees in the two regions dropped from 1.8 million in 1995 to 69,000 in 1998 and that the “majority of the Rwandan refugees had returned home spontaneously.” UNHCR also noted that “The Congolese government updated the figures from 38,000 in 2014 to 245,000 following a pre-registration (estimation) exercise.” [65]

Rwanda’s Influence on the International Stage

In recent years, Rwanda has become increasingly prominent on the international stage, building an ambitious foreign policy that has seen Rwanda or Rwandan officials taking an active role in multilateral institutions. Kagame, when he chaired the African Union (AU) in 2018, spearheaded a wide-reaching reform agenda and was a driving force behind the African Continental Free Trade Agreement (AfCFTA).[66] Rwanda is one of the largest contributors to peacekeeping operations on the continent and Rwandan troops are also intervening bilaterally in the Central African Republic and Mozambique.[67] At time of writing, Rwanda and Benin were holding talks on bilateral security assistance.[68]

Rwandan officials have often cited their own country’s violent past as their motivation for their government’s contribution to peacekeeping operations and willingness to take a proactive role in resolving conflicts on the continent. It was indeed the international community’s complete failure to speak out—let alone intervene—in Rwanda in 1994 that contributed to the deaths of so many. Kagame is the only African leader to have spoken out forcefully following the outbreak of the war in the Tigray region of northern Ethiopia, calling for action by the US, UN, and other African states.[69]

However, Rwanda’s contributions to multilateral operations, under the aegis of the AU and the UN, have also been used to stave off criticism of its human rights record, both domestically and abroad. In response to the UN Human Rights Mapping Report, which details serious crimes committed between March 1993 and June 2003, including by Rwandan troops,[70] Rwandan authorities threatened to withdraw troops deployed to Sudan as part of the UN-AU mission to Darfur.[71] “Starting with Darfur, we have instructed our force commander to make contingency plans for immediate withdrawal as we wait to see how the UN treats this report,” then-Foreign Affairs Minister Louise Mushikiwabo said at the time.[72]

In June and November 2012, reports by the UN Group of Experts on Congo documented Rwanda’s command over the M23 armed group and its abuses in eastern Congo.[73] The Rwandan government instructed Akin Gump Strauss Hauer & Feld LLP, a US based law firm, to critically review the methodology of the Group of Experts’ interim report.[74] Human Rights Watch wrote to Akin Gump Strauss Hauer & Feld LLP to seek input on the evidence used for this report and its source, but at time of publication, had not received a response. Despite the experts’ grave findings that Rwanda had a direct hand in conflict in a neighboring state, on October 18, 2012, Rwanda was elected to a two-year term on the UN Security Council.[75]

Over the years, even countries that were somewhat critical of Rwanda’s rights record have toned down their condemnation of its domestic and extraterritorial human rights abuse, as other strategic interests have become more prominent.[76] One example of this trade-off is the UK-Rwanda Migration and Economic Development Partnership. In April 2022, the UK announced that it had made an agreement, in the form of a Memorandum of Understanding, to send asylum seekers who enter the UK through “irregular” routes, such as by crossing the English Channel, to Rwanda.[77] The deal is a clear abrogation of the UK’s international protection responsibilities and obligations towards asylum seekers and refugees, and was widely condemned.[78] In May, the UK Home Office published its safety assessment on Rwanda, intended to justify the agreement, and conclusion that Rwanda is a safe third country to which to send asylum seekers.[79] Reneging on its past criticism of Rwanda’s human rights record, the UK government’s report downplayed the risks asylum seekers may face if deported to Rwanda.[80] A Foreign Office memo, revealed in court proceedings to challenge the UK-Rwanda deal, stated that, in March 2021, UK officials had informed then-Foreign Secretary Dominic Raab that if Rwanda was chosen as a partner for the asylum deal, the government would need to “constrain UK positions on Rwanda’s human rights record, and to absorb resulting criticism.”[81] Human Rights Watch wrote to the UK authorities to seek information and input on whether the asylum deal had been reviewed in light of the real risk of persecution Rwandan asylum seekers and refugees face in the UK. On October 2, Human Rights Watch received a letter from the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office, on behalf of the Foreign Secretary and Home Secretary, broadly stating that, “Our positive relationship with Rwanda ensures that we uphold our commitment to addressing critical global challenges. We have worked closely together on the partnership to protect vulnerable people seeking safety and opportunity; human rights are a key consideration. The UK and Rwanda are mutually committed to ensuring that this arrangement succeeds.”[82]

In 2021, after decades of tense relations between France and Rwanda, a commission established by President Emmanuel Macron to investigate France’s role in the 1994 genocide published a 1,200-page report concluding that France has responsibilities it characterized as “serious and overwhelming,” including for being blind to the preparation of the genocide and being slow to withdraw support from the government orchestrating it.[83] Since then, the French government has increased political support for Rwanda in its role as “peacekeeper” on the continent, including by reportedly supporting the EU funding of 20 million euro for Rwanda’s bilateral intervention in Mozambique.[84] Rwandan troops were deployed to Mozambique’s Cabo Delgado region in July 2021, three months after TotalEnergies, a French oil and gas company, was forced to suspend a US$20 billion liquefied natural gas project due to insecurity.[85] In addition, Rwanda has taken over peacekeeping operations in the Central African Republic, and filled the gap left, in part, by the departure of French forces announced in 2016 and fully implemented in December 2022. Human Rights Watch wrote to the French government to seek information and input on its support for Rwanda’s military in Mozambique, but at time of writing, had not received a response.

Rwanda’s prominent role in multilateral institutions has turned the country into a leading actor on the global stage while advancing its interests. Mushikiwabo is now the secretary general of the International Organization of La Francophonie (Organisation internationale de la Francophonie, OIF). Kagame was awarded the “Ordre de La Pléiade” by the Parliamentary Assembly of La Francophonie in July 2022, an award which recognizes individuals who have promoted the French language and made contributions to French speaking communities, despite the fact that under his leadership, Rwanda has actively reduced the use of French in official affairs and imposed English as the sole medium of education.[86]

Following this shift and Rwanda’s rapprochement with the English-speaking world, Rwanda became a member of the Commonwealth in 2009. In 2022, President Kagame became Chair-in-office of the Commonwealth, after hosting the Commonwealth Heads of Government Meeting (CHOGM) in Kigali in June. The meeting among heads of state of the Commonwealth, which normally includes discussions on human rights, good governance, and freedom of expression, was muted on Rwanda’s rights record. Journalists reported being blocked from entering the country and prevented from working independently.[87] Additional concerns about human rights violations connected to the meeting, including the arbitrary detention and ill treatment of poor and marginalized people to “clear” the streets, were ignored by the Commonwealth secretariat and its heads of states.[88] In May, a jailed critic said in court he was being beaten and tortured, and that “the prison staff tell us they will kill us after CHOGM.”[89] In January 2023, John Williams Ntwali, an investigative journalist who had been warned by intelligence agents that, “If you don’t change your tone, after CHOGM, you’ll see what happens to you,” died in suspicious circumstances.[90]

Rwanda’s Public Relations Strategy

The Rwandan government is known to invest significant resources in major entertainment, cultural, and sports events as part of a plan to overhaul the country’s economy and attract foreign investors and tourists. Some of these communications campaigns have included the #VisitRwanda campaign and Rwanda’s sponsorship of Arsenal Football Club. Although many countries invest in public relations to promote tourism and boost their economy, some aspects of Rwanda’s strategy have a darker side which may have fueled harassment of those who challenge the narrative it seeks to project.

According to contracts with public relations firms Human Rights Watch reviewed, the government’s strategy includes investing significant resources in communications campaigns to promote tourism and encouraging investment in Rwanda. For example, on May 21, 2018, Myriad International Marketing LLC entered into a partnership with the embassy of Rwanda in Washington, DC. The agreement was renewed twice and on July 2, 2020, Myriad proposed a range of activities amounting to an annual budget of $306,000, including $42,400 earmarked for a journalist and “influencer”’s trip to Rwanda.

However, the Rwandan government’s public relations strategy can also include far more aggressive campaigns using social media platforms and pro-government media to discredit critics. In 2009, then-Information Minister Louise Mushikiwabo signed a $50,000-a-month agreement with W2 Group, a US-based public relations and advertising firm.[91] In its statement of work, submitted to the US Department of Justice under the Foreign Agents Registration Act (FARA), the firm said that “Certain NGOs, such as Human Rights Watch, continue to advance a story of an unstable Rwanda as a means of continuing to attract donors and wield influence in the region …. [G]overnment officials have decided to implement a full-scale public relations blitz communicating the positive story of Rwanda.” The following strategy was described to implement the “public relations blitz”: “We will use a combination of digital and social media (to create our own news and perception cycle) and established print and broadcast media (e.g., The New York Times, The Economist) to leverage their influence with elites.”[92]

The statement of work describes Rwanda’s public relations strategy and may offer some insight into the relentless online attacks and harassment many critics of the Rwandan government face: “We will erect, on free social networks, ‘walls’ of pro-Rwandan data that debunks myths and links to Rwanda's national web site. This will enable us to establish captive audiences on the web, even as we undercut opposition and advance Rwanda's organic search on stories that go beyond the genocide.” This may explain why it has become usual for social media posts, videos, and articles attacking and often publishing false information on individuals, including Human Rights Watch staff, journalists, human rights activists, and organizations, to emerge after they have published content critical of the Rwandan government.

Although many governments resort to public relations firms to manage their image, investigations by the Forbidden Stories consortium of journalists have exposed how reputation management can take the form of more perfidious disinformation campaigns. In February 2023, Forbidden Stories exposed how a team of Israeli contractors claimed to have manipulated more than 30 elections around the world using hacking, sabotage, and automated disinformation on social media.[93] In light of the Rwandan government’s reported attempts to spread disinformation in the US, particularly to tarnish the reputation of government opponents, the vague description of public relations firms’ activities on behalf of foreign governments in their FARA registration statements makes it difficult to assess what particular services firms actually provide and to what degree these may constitute disinformation.

Human Rights Watch wrote to W2 Group and Myriad International Marketing LLC to seek information on the steps taken to ensure that their work does not contribute to the harassment of Rwandan critics. Human Rights Watch spoke with Lawrence Weber, the CEO of W2 Group and Racepoint Global, on August 16, 2023, about the work Racepoint Global did for the Rwandan government at the time. Weber told Human Rights Watch that his firm was not instructed to counter specific critiques, but rather given a broader mandate to increase positive news coverage of Rwanda to counter negative press and diaspora critiques.[94] At the time of publication, Myriad International Marketing LLC had not responded.

A Global Network of Surveillance

On November 16, 2019, Rtd. Gen. James Kabarebe, then-senior presidential adviser on security matters and recently appointed Minister of State for Foreign Affairs in charge of Regional Cooperation, gave a speech at an event organized by the Genocide Survivors Student Association (Association des Étudiants et Élèves Rescapés du Génocide, AERG).[95] “These Hutu… when they are refugees in camps in Malawi, Zambia, Mozambique, Lesotho, Zimbabwe, South Africa, Europe, or in the forests of the DRC… they reorganize and plan the next fight,” he said.

Speaking about the success of Rwandan children growing up outside the country, he listed three names that may be perceived as belonging to the Hutu ethnic group, and warned that “the problem is that their thinking is the same as their parents who wanted to destroy the country.” Kabarebe continued to say that these communities have become too powerful economically, and that their youth is “organizing”:

After 1994, our enemies fled to Congo, others to Tanzania, and in other countries in Africa. Those who had the means fled to Europe. […] Our country is trying to divide them. I am so against genocide ideology I would be ready to use heavy weaponry against someone who criticizes the State. A person with genocide ideology is very dangerous and should never be tolerated. You must know the enemy is there. Everything they do is genocide ideology, for example what they call democracy, freedom of the press, or when they talk about human rights, behind that is always genocide ideology.

The speech provided an insight into the RPF’s continued hostility toward, and discomfort with, many Rwandans living outside the country, whom they sweepingly accused of having taken part in the genocide. It also confirms the government’s use of “genocide ideology” accusations to target Rwandans who disagree with the ruling RPF, including civil society and media who have peacefully promoted democracy and freedom of expression with no reference to the genocide.

In part because of Rwanda’s violent history, there is a large Rwandan diaspora and refugee community living around the world. From its early days in power, the RPF, which consists of many former refugees who grew up in exile in Burundi, Congo, and Uganda, has sought to mobilize support from the diaspora. Part of the government’s strategy has been presented as trying to “harness” the potential for development in the diaspora—for example, Rwanda’s development plan, Vision 2020, aimed to draw on their skills, investment, public relations, and networks.[96] However, as the government consolidated its power and quashed domestic opposition, it has also invested huge resources in monitoring and targeting potential threats to its rule that could emerge abroad.

The Rwandan Community Abroad

With hundreds of thousands of Rwandans still outside the country, in 2001, a unit was established in the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and International Cooperation (MINAFFET) to manage services for Rwandans abroad. In 2008, the Diaspora Desk was formalized into the Diaspora General Directorate (DGD).[97] “We always had a refugee problem. We wanted people to come back home. At that time, it wasn’t about surveillance, but our culture is such that everyone is aware of what everyone else is doing. It’s when Kayumba [Nyamwasa] left that everything took a very drastic turn,” a former RPF member, who was a senior government official at the time, told Human Rights Watch.[98]

In June 2013, US citizen Michelle Martin filed a registration statement under the US FARA, enclosing her consultancy agreement with MINAFFET. Pursuant to this agreement, Dr. Martin was tasked by MINAFFET to “research and analyze Rwanda's post-genocide negative ‘conflict-generated diaspora’ (CGD) and the impact on the conflict cycle in the Great Lakes Region.” One of the proposed activities was to “Map virtual transnational network members, including organizational memberships, cross-network affiliations, researching and documenting propaganda dissemination involving genocide ideology, negation, and trivialization.”[99]

Human Rights Watch wrote to Dr. Martin to seek more details on the nature and purpose of her research on behalf of the Government of Rwanda. Dr. Martin explained that her research focuses on ameliorating the relationships between home governments and the unsupportive, politically active segments of their diasporas, and that she completed a number of literature reviews and statistical mapping exercises, on a macro level, to determine which government practices were more likely to support peace processes.

Patrick Karuretwa, who was then Kagame’s personal secretary, signed the statement on behalf of MINAFFET. When asked whether she had ever worked with or taken any direction from Karuretwa, Dr. Martin stated that her research was self-directed and that, other than as specified in her consultancy agreement, she did not receive any specific instructions on what to research from him or anyone else in the government.

According to a former senior government official, Karuretwa was involved in developing the Rwandan government’s global surveillance structure. In 2021, Karuretwa, who is alleged to have been involved in the ongoing judicial case against former ambassador Eugene Gasana,[100] was promoted to the head of the RDF’s newly created Department of International Military Cooperation.[101] In this new role, he coordinates with the defense attachés and associates in Rwandan embassies globally.[102]

The Rwandan Community Abroad (RCA), a group of associations tied to embassies and the foreign affairs ministry, is charged with mobilizing Rwandans abroad.[103] The RCA has 68 affiliated associations in different parts of the world, including 32 in Africa, 22 in Europe, 8 in Asia, 4 in America, and 2 in Oceania. The Rwandan government has received support from the International Organization for Migration (IOM) and the EU to devise and implement a global diaspora engagement strategy.[104] According to the EU Global Diaspora Facility (EUDiF), a project funded by the EU’s Directorate-General for International Partnerships, the “success” of Rwanda’s approach to diaspora engagement has been to work with RCA chapters, which are able to “mobilise people and resources quite effectively.”[105] The Facility added that “the Government of Rwanda has also sought to reach out to those who are politically neutral and invite them to participate in Rwanda’s development and reconstruction.”[106]

Engaging the diaspora and offering its members opportunities to meet and reconnect with their home country is not a human rights violation. However, according to this research, the Rwandan government’s outreach goes beyond opportunities to reconnect and involves threats, surveillance, and harassment, as the government seeks to pressure Rwandans who do not support the RPF, including refugees and asylum seekers who have sought international protection from the Rwandan government itself.

For example, many asylum seekers and refugees expressed fear of Rwandan agents infiltrating domestic refugee agencies and UNHCR, particularly in East and Southern African countries. Some said that they refused to engage with the UN refugee agency on protection issues, or that they either refrained from requesting asylum or did so under a false name or nationality, to protect them from being targeted by the Rwandan government.

Some refugees, especially in Europe and the US, cited events organized by the RCA, such as “Rwanda Day,” as examples of the diaspora community’s attempts to mobilize and intimidate people, as well as an occasion to assess who does or does not support the ruling party. The government describes “Rwanda Day” as “a sort of gathering where the Rwandan community abroad gets to understand its role in shaping the country’s future.” MINAFFET describes “Rwanda Day” discussions as focused “on the country’s development goals, business environment and opportunities available for those wanting to be part of a country on the move.”[107] An opposition figure living in exile in Belgium explained in an interview: “You have to be wise—either you go to their meetings and ‘Rwanda Day’ celebrations or you have to watch your back.”[108]

Spreading Fear Abroad

“Before, the RCA were hiding. They are openly saying they work for Kigali now. Pressure increased after the speech by General Kabarebe.”[109]

Many refugees and asylum seekers interviewed for this report described the RCA associations as arms of the Rwandan government abroad. They expressed concern about the harassment and pressure refugees and their family members face to join the association and to support the ruling party.

In Australia, Belgium, France, Kenya, Mozambique, and South Africa, interviewees said the Rwandan community was divided between what they referred to as the “diaspora”—members of the RCA or other Rwandans abroad who were able to travel freely to Rwanda—and the “refugee” community. However, some said that certain members of the “diaspora” had refugee status. The “diaspora” was generally perceived to be aligned to the RPF and the RCA, and many refugees described being afraid of its members and their campaign to have refugees join them.

In South Africa, many asylum seekers and refugees told Human Rights Watch that the RCA, in recent years, had become increasingly aggressive in its efforts to widen its membership base. Some said they were worried that the RCA was exploiting the precarious situation of Rwandan asylum seekers and refugees—where many struggle to get permanent refugee status, to renew or obtain permits and other identification documents allowing them to maintain legal status, and to get documentation allowing them to work, study, and travel—to convince them to join the RCA.[110]

“The RCA are trying to mobilize youth. They organize parties, and they tell youth: ‘don’t follow your parents, they committed genocide,’” said one Rwandan asylum seeker and parent in Cape Town, South Africa. “When you can’t afford enough for your children, they are there offering beer, allowing them to drink…. They tell them: ‘why are you living this life? [Rwanda] is good. Your parents are lying.’” Then, she said, the youths are offered passports and are told they can go back to Rwanda: “They were made to say the oath. You know what it says in the last line? If you betray the RPF you will die.”[111]

The “oath,” a loyalty pledge to the RPF, is read out during ceremonies hosted at embassies. In November 2020, a video of such a pledge at the Rwandan High Commission in the UK was leaked online. It showed a group of people saying, “If I betray you or stray from the RPF’s plans and intentions, I would be betraying all Rwandans and must be punished by hanging.”[112] Those pledging promised to fight “enemies of Rwanda, wherever they may be.”[113] Several refugees interviewed for this report expressed fear that once their fellow refugees had given in to pressure to join the RCA and pledged loyalty to the RPF, continuing to be in direct contact with them would put them at risk.

“The embassy created the RCA …. They have committees everywhere,” said one refugee leader in Cape Town. “If you have a business here in South Africa, they come and ask for money for Kigali…. They intimidate by sending someone and say, ‘if you don’t join the RCA you will have problems.’”[114] Human Rights Watch reviewed one of the communications being circulated by the RCA requesting payments.

In Europe, Rwandans said that embassies could either facilitate or block access to services, for example to transfer land titles or requests for official documents, depending on whether the person requesting was a member of the RCA or not. A Rwandan living in France said that when he went to the Rwandan embassy to have his passport renewed in 2019, he was confronted about not being a member of the RCA. “Instead of accepting my application, they asked me for my RCA card. Since I didn’t have one, they took my passport photo and asked for 20 euro, and used them to create an RCA card,” he said. He explained that since he was forced to join the RCA, he felt pressure to explain why he could not accept invitations to events, including around visits by the Rwandan president, to avoid being flagged as someone who does not support the government.[115]

Several Rwandans who are known for being critics or related to government opponents said they were unable to get paperwork, from certificates of good conduct to the documents necessary to transfer title deeds to family members who remain in Rwanda, because the embassy perceived them as being “against the government.”[116]

A refugee who fled Rwanda after being unlawfully detained and tortured in 2010, said he continued to live in fear despite being resettled to the US in 2018. He was granted asylum due to the severe abuse he suffered in detention and the politicized trial he faced. “Since I’ve arrived in the US, I rarely let anyone come to my house. I never go out, and if I do, I always finish my drink before [it] leaves my sight,” he told Human Rights Watch in May 2022, sharing a widespread fear among Rwandans abroad of being poisoned.[117] In May, he said he discovered that his closest friend was working with the Rwandan embassy after seeing him wearing clothing with the RPF logo on it. When he confronted him, his friend offered to connect him with the embassy: “He said he could help me work with the government. He said the embassy asked him to work to defend the Rwandan government…. He knows my habits and my movements. He’s been to my house.”[118]

Pressure to Return to Rwanda

Some refugees and asylum seekers in Mozambique, South Africa, and other countries in Southern Africa described how the government tried to convince or pressure them to return to Rwanda. Several refugees living in Mozambique, who had previously been vocal political opponents, have reportedly since returned for fear of being targeted by the government. In one case, a person interviewed by Human Rights Watch said he was under intense pressure to return to Kigali and described the constant threats he was facing.[119] Months after the interview, some of his former contacts informed Human Rights Watch that he had returned to Kigali and that it was no longer safe to communicate with him. For their security, the names and identifying information of those who have returned to Rwanda have been withheld from this report.

Many Rwandan refugees said that they believe the increasing pressure to return is linked to the government’s efforts to open embassies and sign security partnership agreements with Southern African countries.

A diaspora leader in Cape Town was named by several refugees as the person coordinating RCA activities in Western Cape Province. “He is the person to go to once people agree to work for the government, and he organizes their passports and their return to Kigali,” said one refugee.[120] “They are coming for our children as well, because they can’t go to university here if they don’t have identity papers. They offer them passports, green cards, work permits, so they can go to school. I’m an Uber driver [working without papers], I can’t apply for a job or get a work permit here,” said another, stating concerns about the same diaspora leader.[121]

In Mozambique, a diaspora leader was also said to have approached refugees and told them to return. “In February [2022], [the diaspora representative] called my friend and told him to warn me that if I don’t want to die, I should go to the embassy,” said one refugee in Mozambique. He said that two weeks later, he was approached by a different person who told him he was in danger and should go to the embassy.[122]

Another interviewee told Human Rights Watch about how his relative became afraid after Cassien Ntamuhanga, a Rwandan opposition activist and asylum seeker, was forcibly disappeared by Mozambican security forces, in the presence of a Kinyarwanda speaker in May 2021.[123] “He [the relative] joined the diaspora after Ntamuhanga was taken. He was afraid. He went to the embassy, and they sent him to Kigali.” Human Rights Watch confirmed this story with two other sources close to him, whom he had also informed of his decision to return due to his fear of the Rwandan government’s reach in Mozambique. The refugee said: “Today the embassy expects Rwandans to go to the embassy and then to Kigali to show they support the government. [The diaspora representative] used to give plane tickets [to Kigali] through the diaspora association, now it’s coordinated through the embassy.”[124]

Asylum seekers and refugees in Mozambique explained that the situation had deteriorated since Rwanda opened an embassy in Maputo, the Mozambican capital, in June 2019.[125] “Once the embassy opened, the threats became terrible. They call us. They called me three times since Révocat [Karemangingo][126] was killed saying: ‘if you don’t go to the embassy, we will accompany you to where Révocat is.’ They mean the graveyard,” said one refugee. “They call me from private numbers, but the person speaks Kinyarwanda. I don’t want to go. I’ve spoken to UNHCR and INAR [Instituto Nacional de Apoio aos Refugiados, the Mozambican National Institute for Assistance to Refugees] but nothing’s done.”[127]

Another said: “The embassy has been meeting with a lot of Rwandans. They try and get them back to Rwanda. They take people back and show them how great Rwanda is. They say they want to unite Rwandans […] but the government is always threatening people. There is no trust between people. If one person says something bad about the government, they will be afraid of people telling on them.”[128]

Lionel Richie Nishimwe (Zambia)

One case is particularly revealing of the methods used by the Rwandan authorities and the outcomes for those who choose to return. Lionel Richie Nishimwe was a Rwandan refugee who spent most of his life in Zambia. A lawyer and leader in the local refugee community, Nishimwe was well-educated and an advocate for the Rwandan community in Zambia.

On May 3, 2016, Nishimwe repatriated to Rwanda, “after being enticed by the representatives of the Rwandan High Commission in Zambia,” according to a letter he later sent to his contacts outside the country. In the following days, Nishimwe posted photos of himself in a bathrobe, standing in front of the Diplomat Hotel in Kigali on Facebook.[129] In the following days, he continued to post photos of himself at the hotel. An invoice for his stay at Kigali’s Diplomat Hotel from May 3 to 20, 2016 was signed by Nishimwe “on behalf of NSS [National Security Services].”[130]

In the months between May 2016 and early 2017, Nishimwe posted a series of articles refuting his previous criticism of the Rwandan government, including one titled “Why I Am No Longer a Rwandan Genocide Denier.”[131] The tone of his articles and social media posts changed, and he began posting exclusively pro-government articles, attacking government critics, and claiming that he was misled by genocide deniers and opponents of the government outside the country.